How We Do Things – Evolving our Planning Practice

This content comes solely from my experience, study, and a lot of trial and error (mostly error). I make no claims stating that which works for me will work for you. As with all things, your mileage may vary, and you will need to apply all knowledge through the filter of your context in order to strain out the good parts for you. Also, feel free to call BS on anything I say. I write this as much for me to learn as for you.

This is part 2 of the How We Do Things series.

Introduction

Planning is a key part of any software effort. It serves multiple purposes in an organization, from budgeting to work scheduling, and it’s not always a science. We’re going to talk about how we do planning on my team in two installments, starting with how our planning process has evolved over time, and moving into the mechanics of what we do in the next post.

How we used to plan

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before. At the start of our LIS project, we planned and defined the whole thing. We specified everything to great detail, put it on a Gantt chart, and put it on the wall. Then we went to work and created something that didn’t bear a lot of resemblance to the plan.

When we finished we were almost 6 months off the Gantt chart’s projected timeline. I didn’t consider us late, because we weren’t. Scope creep had set in, standard organizational delays, and over-optimistic and naïve estimates led to us creating a picture far in advance that didn’t in any way represent reality.

Planning in great detail far in advance of the work being done got us in trouble, and it allowed the perception that we were failing to set in. It created a morale problem on the team, put us under a ton of undue pressure, and made the project into a death-march of sorts.

When all was said and done, we were hugely successful in delivering the project, and I would consider it a heroic effort given what we were up against. But while it was underway, having that detailed “plan” was a boat anchor attached to our necks.

So we don’t do that anymore.

Planning isn’t all-or-nothing

Somewhere along the line someone decided that you had to plan an entire project, in detail, up front, for…some reason. I’m not sure what that reason is, to be honest, because after all this time we know that those plans usually end up falling down. If the reason is budgeting, you’re going to be off. If the reason is resource allocation (hate that phrase) you’re going to be off. If the reason is setting deadlines, you’re likely going to be off. At the end of the day, if the project turns out to have mirrored the plan up front, well, you’re either better at lying than I am, or you’re a dark wizard and I wish to apprentice for you.

When we continue to go through the motions of this huge up-front planning effort in the name of whatever gain we think comes from it, even though we know that at the end we will likely not have actually realized that gain, we are, simply, lying to ourselves and the organization. If we know that today’s plan is next week’s joke, why do we keep doing it this way? As the saying goes, the definition of insanity is repeating the same action expecting a different result.

The wastes of detailed advanced planning

We came to realize that there was a lot of waste associated with a lot of up-front detailed planning.

The first waste is inventory. Carrying excess inventory is one of the seven primary wastes in lean manufacturing, and in our case, defined work that is not yet in progress is inventory.

This inventory is wasteful because after this work has been done, any number of things can happen that will nullify that work. Changing requirements and changing priorities can have a big impact. When we change requirements or learn more about the needs of a pre-planned system, we end up throwing away a lot of that planned work and starting over. This happens all the time in our world, where certain things will simply not surface until well after we have identified a set of features, and trying too hard to get them all planned out beforehand leads to tossing those stories and starting over.

Changing priorities leads to a different but equally wasteful problem in that we have planned the work, but priority shifts will ensure that the work continues to sit inert as inventory and that the organization is not realizing any value from the planning work done. In essence, we wasted our time putting a lot of detail on this work.

Finally, there’s the cognitive waste of having work planned and defined well in advance of development, and then losing scope of everything you had talked about by the time you actually get around to implementing. Basically, we were finding that anything we planned more than a month or so in advance of development led us to essentially repeat that planning work near the time of development in order to make sure we were still on the right page. This is an example of excessive motion, another waste identified by lean.

Baby Steps

As we migrated from a waterfall to a scrum approach, we started planning much smaller. We got to a point where we were doing detailed planning about a month in advance. Even this was too much, but it was a step in the right direction.

We realized that we were never going to get to a point where the organization wouldn’t throw new things at us on at any given moment, and we were never going to achieve the kind of workflow protection that scrum claims to offer (more about this when I get to the post about Kanban). Even planning in detail a month in advance was leading to the same wastes as before. Less of it, to be sure, but it was there. So, we made another change.

The other extreme

The next step in our evolution was to essentially throw planning out the door altogether.

We decided if our plans were just going to go to waste anyway, that we would JIT every ounce of it. This meant no planning and no specs until it was time to work on them. We carried near-zero inventory of pre-planned work, and had no problem handling changing priorities.

The problems with this approach became quickly evident though as we realized that we had basically no roadmap. We couldn’t tell you what we were doing next week, let alone next month, with any confidence. As the organization started to do some long-term strategic planning, I was unable to provide any information about where these plans could fit into our workflow beyond “yeah we can work on that, but maybe some other stuff falls by the wayside, but I don’t know what that stuff is.” This is obviously an unacceptable situation.

We needed a compromise that served our needs and the organization’s.

The Space-Time Continuum of Project Planning

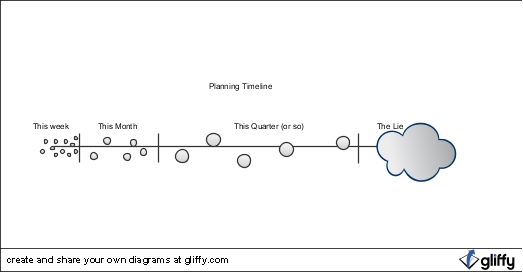

For us, planning is now broken up into three distinct parts: immediate, near-term, and long-term.

</p>

In the next part of this series I will talk about the mechanics of each segment, and how it fits together to form the whole.

In general the idea is this: I can tell you with great detail and confidence what we are working on in the next few days. In the next month or so I have a pretty good idea of what’s coming and the scope of the work, but it’s not planned and specified in minute detail yet. In the upcoming quarter or so, I have a roadmap of things that we will get to if current conditions and priorities remain the same. Beyond that, we have a general idea of where the products should go and what initiatives may be on the horizon, but they are just a general idea, and we will not spend much time doing anything more than exploratory information gathering until we are past what we are doing now.

On this continuum, the things to the right are very top-level and amorphous by design. There’s a real chance that things far to the right will stay far to the right for the rest of time. Stuff closer to the left is viewed as “real work” and we will get to it soon, or may be working on it now. Maybe some things get inserted there along the way, but we have scope of what items they will move to the right.

The stuff furthest to the right is not really affected by changes to the left because it’s far enough away from the gravitational field of work in progress. It’s like the stars at the edge of a galaxy, largely unaffected by the gravity of the black hole at the center, and held in place by the cumulative gravitational affect of millions of other stars.

In this category we may have things like “we’d really like to put an iPhone app in play to interact with some service at some point”. We keep track of the fact that that’s a desire, but it’s barely visible as a dull dot through a telescope. In our spare time we may dream about the form of these features, but no real work gets put into them. It’s more of an idea bucket. At such time as the organization decides it’s a strategic priority, however, it comes out of the cloud and moves into a place where we know we will be getting to it, and the planning process described in the next post begins.

Next up we’ll talk about how we do planning for each segment of the continuum. Stay tuned!

Technorati Tags:

how we do it, improvement, lean, management, quality, software, team, planning