Kanban In Time-Boxes: The Cadence of WIP and Sprints

A comment that was left on a previous post, and a response that I made to the comment, got me thinking about Kanban and time boxes such as Sprints or Iterations some more. As I stated in my response, I don’t think time boxes are “not Lean”, at this point. I still advocate and coach Scrum at my office. It is a significant improvement over the previous waterfall-ish chaos that our teams have operated in. I also advocate and coach Kanban. At times, the realms of Scrum and Kanban overlap, as well.

“’There is nothing either good or bad’, said Shakespeare, ‘but thinking makes it so.’”

– Dale Carnegie, How To Win Friends And Influence People, p. 68

I don’t necessarily think time boxes like Scrum sprints are good or bad, anymore. The only way to know whether or not any part of our process is good or bad is to measure and monitor the process and use leading and trailing indictors to tell us what our problems and inefficiencies are and are not. With the right information in hand, we can ask what the economic impact of the process that we are following, actually is. This will tell us whether or not any part of our system is good, bad, or otherwise.

Given my current feelings about Scrum and Kanban, I thought it would be appropriate to outline how I think time boxes and Kanban can coexist. Corey Ladas has already put in a lot of time and effort in his Scrumban book and his blog over at LeanSoftwareEngineering. I recommend reading his thoughts on this subject. His work along with the writings of Karl Scotland (Kanban, Flow and Cadence. What Is Cadence. Does A Kanban System Eschew Iteration. etc), David Anderson and the rest of the KanbanDev mailing list are a huge inspiration to this post. I am probably going to repeat a lot of information from these sources, honestly. They are worth repeating.

Traditional Scrum and Sprints

In the traditional, strict type of Scrum that seems to be so popular these days, work is typically scheduled into sprints. The spring may be 30 days, it may be 2 weeks or another time frame that has been chosen by the team. The beginning of this time box marks the sprint planning session. Work is then done throughout the sprint, and a release is potentially done at the end of the sprint (and yes, I’m oversimplifying the description of Scrum and sprints to illustrate the basic time box of sprints).

<img style="border-top-width: 0px;border-left-width: 0px;border-bottom-width: 0px;border-right-width: 0px" height="95" alt="image" src="https://lostechies.com/content/derickbailey/uploads/2011/03/image_5C4CE04D.png" width="588" border="0" />

Within the individual sprint, the work that is scheduled is essentially a black box to the outside world. The team that is doing the work has made a commitment to get a certain amount of work done within that time box. For example, a team may have committed to 2 features in the first sprint, and another 3 features in the second sprint. At the end of each of these sprints, the team can release the software that they have developed, up to this point.

<img style="border-top-width: 0px;border-left-width: 0px;border-bottom-width: 0px;border-right-width: 0px" height="227" alt="image" src="https://lostechies.com/content/derickbailey/uploads/2011/03/image_14F78A5B.png" width="591" border="0" />

The scheduling of features into sprints has a good number of benefits including regular feedback from the customer and the ability for the customer to reprioritize the work on a regular basis. The time box of a sprint helps to create a regular cadence for the development team, management team, customer, etc. This rhythm helps to keep everyone in sync and keep the process moving.

Failed Sprints

Unfortunately, the real world does not always play well with us. There are times when a feature that was scheduled and committed to, will end up taking more time than was originally planned. There may be some technical hiccup, there may be some breakdown in the communications and description of the work to be done. Or there may be some other problem that is causing the work to be delayed. Whatever the cause is, we sometimes find ourselves in a situation where the work that we started during one sprint is not complete by the end of that sprint. One possible reaction to this situation is to continue that feature’s development into the next sprint. However we react to the situation, though, we should be digging into the underlying root causes of the problem so that we can work to prevent this problem in the future.</p>

<img style="border-top-width: 0px;border-left-width: 0px;border-bottom-width: 0px;border-right-width: 0px" height="267" alt="image" src="https://lostechies.com/content/derickbailey/uploads/2011/03/image_74704AA8.png" width="591" border="0" />

To the world outside of the team, looking at the black box of the sprint, Sprint 3 may have been a failure. The customer expected Feature 6 and Feature 7, but only Feature 6 was delivered. It may not have taken much additional time for Feature 7 to be completed in the next sprint, but the original commitment was not met. Moving into the next sprint, though, the team committed to three more features on top of the continued feature, and they were able to deliver them. So, there was some lag for Feature 7 to be delivered, but it eventually made it out and the team got back to their normal pace of development.

Cycle Time vs Lead Time

The black box of sprints is rather odd, if you ask me. From the outside perspective, you see features start and stop at the beginning and end of the sprint. That doesn’t match up to the reality of how I see software development occurring, though. If this were true, then in the above examples we would have to add additional team members during Sprint 2 and Sprint 4.

Let’s peak under the covers of the black box for a minute. In my experience, the actual development process for these features is not usually a start and stop based on the sprint start and stop. The reality that I work in usually has features being started and stopped at various intervals within the sprint. For example, there may be some administrative need during the first sprint that prevents all of the team members from being fully engaged throughout the sprint. Then, in sprint 4, the work seemed smaller than usual after the continued Feature 7 was completed. This let the team split off a little more than usual and complete more features than they normally would.

<img style="border-top-width: 0px;border-left-width: 0px;border-bottom-width: 0px;border-right-width: 0px" height="267" alt="image" src="https://lostechies.com/content/derickbailey/uploads/2011/03/image_61BB50F1.png" width="591" border="0" />

This type of start and stop within sprints is pretty much par for the course, in the Scrum teams that I have worked on. The actual cycle time – the time it takes to push a feature from from start working to finished working – is not usually the same as the lead time. The lead time – the time it takes for a feature to go from planning to delivery – is fixed to a regular schedule in these sprints. If we are operating on a 30 day sprint, we know that the lead time for any feature is going to be 30 days. But by looking under the covers, we can see that the cycle time of a feature might be much less than 30 days.

Looking at sprint 1, we can see that Feature 1 took roughly half of the sprint to complete. If we have a cycle time (CT) of 15 days to complete a feature, but the lead time (LT) of 30 days to deliver the feature, then our process cycle efficiency (PCE = CT / LT) is only 50%.

Authorize Work By Capacity, Not Schedule</p>

There may be a problem worse than low PCE, though. If Feature 1 was done earlier than planned and the team members were not allowed to pull any additional work into the sprint because the sprint had already been scheduled and started, then these team members may be sitting around with nothing to do until the next sprint starts. I understand that this may be an extreme case, but I have seen it happen. Some teams take the sprint planning and black box of the sprint as gospel and will not allow additional work to be pulled into the sprint if a team finished early. The point that I’m trying to get at is not that the teams are doing Scrum right or wrong. That distinction can only be made by examining the individual team and their situation. What’s right for some teams may not be right for other teams. What I am saying is we don’t have to limit our work to a pre-determined schedule, the way sprints are traditionally managed.

In our example, we know that the work that started work on Feature 2 wasn’t available immediately at the start of the first sprint. We can’t do anything about that – they get started later than the team working on Feature 1. However, the Feature 1 team does not have to just sit around and wait for the sprint to end before they can continue working. When the team has capacity to do more work, let’s go ahead and let them do more work. We can easily re-arrange the work that needs to be done based on capacity instead of scheduling. All we have to do is let the team plan and start the next feature as soon as they have the capacity to begin working on the next feature. By working in this manner, we are more likely to keep all of the team members working throughout all of the project lifecycle.

<img style="border-top-width: 0px;border-left-width: 0px;border-bottom-width: 0px;border-right-width: 0px" height="91" alt="image" src="https://lostechies.com/content/derickbailey/uploads/2011/03/image_21190482.png" width="560" border="0" /> **Figure 5.** Working to Capacity, Not a Schedule

In this process, we can see that once a team has finished a feature, they now have the capacity to work on another feature. Therefore they pick up the next feature, plan it and begin to work on it immediately. The net effect of this is that we now have a team that is more fully utilized and we also have what appears to be less fluctuation of the amount of work that is current in process. Since we are not scheduling work to be done in a sprint, we are not varying the number of features in that sprint according to how long we think an individual feature will take. We have two teams, and those two teams work when they have capacity.

Although one advantage of this type of work authorization is the better utilization of our teams, we are not looking for 100% utilization of any individual resource. Any study into the world of queuing theory will quickly show that 100% utilization is detrimental to the work in the system. After all, a road that is at 100% utilization is called a parking lot. One thing to note in the examples, though, is that I am not talking about only writing code or only testing or only analysis. In fact, I’m not talking about any of the steps or activities that actually occur in a software development process. I am making the assumption that the features in this example are taken from “concept to cash” – from beginning to end, ready to be put into the hands of the customer. From this perspective, a higher utilization of the entire team is what we are looking for, not higher utilization of individual resources in that team.

There are other advantages to working by capacity instead of schedule, too. For example, if we are not scheduling work, we can let a customer re-prioritize the backlog any time they want. They do not have to wait until the next sprint begins. They can say “this feature is now critical” for any reason they want, and the team that finishes their current feature first, will pick up the new critical priority. The only time a feature cannot be re-prioritized, without incurring significant cost, is when that feature has already been started. There are a lot of different ways to allow the continuous prioritization of work. For some great ideas on how to do this I highly recommend reading the Scrumban book and Corey Ladas’ blog.

When working to capacity we can introduce more formal process and notions of how to signal that we are ready for more work. This signal is often done in the form of a kanban – a signal to do work. The mechanics of kanban and a Kanban system are a much greater topic than I want to talk about here, though. I have several other posts that discuss the mechanics and some of the non-mechanical parts of a Kanban process, and there are many other great resources out there, including once again – the Scrumban book and the writings of Karl Scotland and David Anderson.

There are still other advantages to working in a Kanban style of workflow. The list is greater than I can go into at this point, though. I encourage you to do the follow-up research via the reference material that I have pointed to and will point to through the rest of this article.

Work To Capacity, Release By Sprint

As I said at the start of this article, I don’t believe sprints are necessarily bad. Even when you consider the scheduling of work vs authorization of work by capacity, I don’t think sprints are bad. Furthermore, I don’t think working to capacity is incompatible with sprints.

In the book, “Lean Solutions”, Womack and Jones talk about the concept of the “Fundamental Unit of Consumption”. This is the idea that we should be asking the customers what do the expect, from a complete solution standpoint? What unit of consumption do they want to receive, to provide the most value to them immediately? The authors go on to talk about how our society’s units of consumption have changed over time, as we all become more and more busy. We have less and less time to make every decision and we are more and more likely to buy bundled packages that provide many products or services.

“In the course of economic history, consumers have bought an ever-wider variety of ever-more-sophisticated objects. Oxcarts, donkey carts, horse-drawn carriages, Model T’s, SUVs – things that were made useful by purchasing a growing range of ancillary items and services, such as ox feed, donkey feed, gasoline, financing, insurance, spare parts, maintenance, and repairs.”

– James P. Womack and Daniel T. Jones, “Lean Solutions”, p. 253

It’s easy, reading on through this chapter, to see how we can easily extend the fundamental unit of consumption into the delivery of software. I’ve already touched how sprints provide a cadence for the overall software development process. This can be an important selling point for some customers. There will be times when a customer will only be available for relatively short periods of time, on a regular basis. It would be good to fit the cadence of the development effort to this availability. After all, some of the primary benefits of Scrum and sprints around found in the synchronization of the customer and team.

With this in mind, and thinking about the befits of working to capacity, we can overlay the sprint schedule that a customer may want on top of our continuous development effort.

<img style="border-top-width: 0px;border-left-width: 0px;border-bottom-width: 0px;border-right-width: 0px" height="195" alt="image" src="https://lostechies.com/content/derickbailey/uploads/2011/03/image_2BD65BD7.png" width="591" border="0" /> **Figure 6.** Overlaying Sprints on Continuous Development

When we overlay the sprints on top of this continuous development effort, we can see how a feature may be started prior to a release, but may not be finished for that release. This scenario should sound familiar – Feature 7 in the discussion on Failed Sprints is another example of when that happened. In this case we are not going to treat any given sprint as a failure simply because we had work that was not completed. Since we are no longer scheduling work for a sprint, the criteria for a successful sprint has changed. We may need to think about other circumstances that may arise during the sprint, or other attributes of the sprint, to consider it a success or failure. It may come down to something as simple as “did we deliver any customer facing value?” The individual reasons for saying a spring is a success or failure, though, comes down to the individual teams.

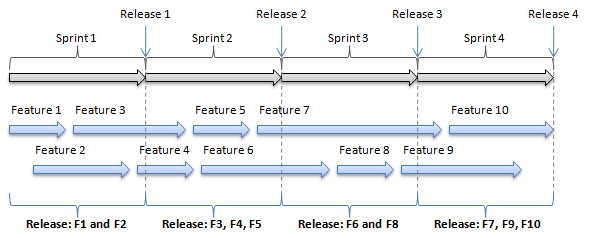

What we can do, now that we are working to capacity, is monitor which features are ready to go at the sprint delivery point. For example, in sprint 1 of Figure 7, we can see that both Feature 1 and Feature 2 were started and Feature 3 and 4 were started but not completed. This would mean that we can deliver Feature 1 and Feature 2 in Release 1. In sprint 2, we completed Feature 3, 4 and 5, which allows them to be delivered in Release 2, and so on through all 4 sprints.

Figure 7. Feature Release by Sprint

Only One Of Many Options

The continuous development, facilitated by working to capacity, delivered on regular intervals, is only one of many options for mixing and matching the cadence of development and releases. There are also additional aspects of software development that may need a regular cadence, as well. I have not talked about retrospectives or kaizen events, release planning and demo sessions, or many other aspects of the software development process. What I have tried to show, though, is that the notion of time boxes like a sprint are not necessarily waste. They can be used with continuous development efforts and pull based authorization of work, such as Kanban systems. It only takes a little bit of effort and understanding of the different rhythms that we actually need to account for. We only need to separate items such as release, retrospective, and work to see how we can reorganize them into the correct cadence for our team and our customer.

But That’s Not Scrum!

I know I’m going to rile up some of the Scrum fundamentalists out there. For those of you who will claim that I have no understanding of Scrum or what a “sprint” really is, I offer up my experience as a direct agile practitioner and coach for the last 2.5 years and a lean-agile-oriented learner and process improvement seeker for the last 5+ years. I’ve learned a lot in that time and one of the key points that I’ve learned about Scrum, XP, and every other agile methodology is that the only viable answer to the question of “what is the right way to build software”, is “it depends”. Or, as Bob Martin stated it, “do a good job”.

There is no one way to do software development right. There is no “one true way” or “silver bullet”. Anyone that tells you there is, is selling something. Even the scrum gurus like Ken Schwaber state that, in no uncertain terms, in books like “Agile Project Management With Scrum”.

“Scrum is not a prescriptive process; it doesn’t describe what to do in every circumstance. Scrum is used for complex work in which it is impossible to predict everything that will occur. Accordingly, Scrum simply offers a framework and set of practices that keep everything visible. This allows Scrum’s practitioners to know exactly what’s going on and to make on-the-spot adjustments to keep the project moving toward the desired goals.”

– Ken Schwaber, “Agile Project Management With Scrum”, Introduction p. xvii

So, then essence of Scrum, then, is to think for yourself and do what needs to be done to keep the project moving toward the desired goals. If our goal is to follow a strict Methodology and set of rules, then we can follow the strict planning and scheduling activities of Scrum proper. However, if our goals are to produce high quality software as quickly as possible, delivering to the customer as often as possible, then we can include some additional concepts and process control systems like Kanban. The choice to “do the right thing” is not left to the methodology frameworks or methodology authors. The choice is ours to make in the context of our team and customer needs.