Branch-Per-Feature: How I Manage Subversion With Git Branches

Anyone that follow me on twitter likely knows that I’m a big fan of Git these days. I’ll spare you the gushing heart felt nausea of how it’s so awesome and skip right to the point, though: I don’t always have the luxury of being able to use Git. For example, my current team has been using Subversion for quite some time. Changing source control systems is not an easy thing to do when your system is as large as this one and has several key points of the development / build process tied directly to the existing source control. So, rather than be forceful and pushy and tell everyone on the team that we need to use git (most of them are already using or learning git, so there’s not much need to preach the good news), I decided to approach the situation a little differently.

Git-SVN? No, Git+SVN

I’ve never had any luck getting git-svn to work. I’ve tried several times on several different repositories, and it always bombs on me for one reason or another. But I still want to use git to manage my local subversion checkout. Rather than fight against the built in functionality in hopes that I would get it working, I decided to follow up on a comment that I Scott Bellware made about putting a git repository inside of an svn checkout. It’s not the “git-svn” functionality of git… it really is “git + svn”… and it turns out that this is easy to setup, fairly easy to manage and provides a lot of flexibility in working on a large codebase.

I want to let you know up-front, though, that managing git + svn in the manner I’m describing here does add some administrative overhead. This is not a “free” solution. It has a cost associated with it, so it must be evaluated as one possible option for your situation. Like most other tools that we have in our toolbox, understanding where your situation sits on the cost-benefit curve is important.

Setting Up Git+SVN

Getting setup to run git + svn is very straightforward. There are only a few things you need to do. I am assuming that you are already familiar with both git and subversion, though. If you’re not, there are some great tutorials out there on the inter-webs (I’m particularly fond of Jason’s Git For Windows Developers series. He did a great job with that series.)

1. SVN Checkout

There’s nothing special about this. Follow your team’s standard practices for what to checkout from your subversion repository. For my team, we checkout the entire trunk. It’s a massive amount of information to pull down, but we seem to use most of it on a regular basis.

2. Initialize A Git Repository

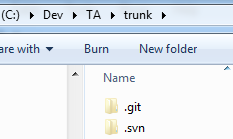

Run a “git init” from the root folder of your subversion checkout but DO NOT add / commit to the git repository, yet! You need to complete steps 3 and 4 before doing that. This will create your .git repository. I’ve got a .git and a .svn folder sitting right next to each other in my svn trunk checkout, now.

3. Gitignore The .svn Folder

This step is very important. You do not want your git repository to be littered with constantly changing .svn folder contents. For one thing, it makes the management of your git commits difficult because you have to sift through more data than you want to make sure you’ve staged / committed the right files. More important, though, is that you can very easily corrupt your svn checkout if you don’t do this!

Imagine having git make modifications to your .svn folder contents while you are switching between branches, then doing an svn update and getting a merge conflict in the .svn folder. That does not sound like fun to me.

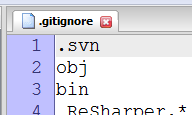

To keep things clean and simple, add .svn to your .gitignore file.

You should also take the time to add your standard .gitignore settings at this point. My list has grown a little, but the basics are still the same as when I posted them, a while back.

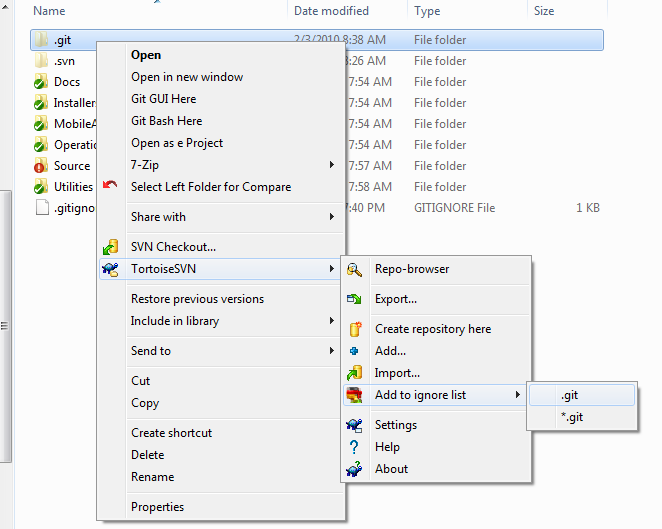

4. SVN Ignore The .git Folder

Subversion doesn’t need to know about your git repository, either. More specifically, you’re team members don’t want to know about it… ever… imagine 3 team members managing their branches with git and one of them accidentally commits their .git folder to subversion. The next time you update from subversion, it would fail because the folder exists. Now imagine that someone does a clean checkout from subversion and receives your git repository in the mix. If they want to use git to manage branches, they would just start using git because a repo exists. The next time either of the two git users commits to subversion, they will update / overwrite the git repo in subversion, and the next person to update from svn will have a clobbered git repo. That’s one mess I don’t want to clean up.

Do yourself and your teammates a favor: tell subversion to ignore the .git folder.

5. Add Everything To Git

At this point you can add the contents of your svn checkout to your git repository. There’s nothing special to do or remember here… just go about adding the files in whatever manner you prefer.

Managing Git+SVN

Since subversion is the system of record in this setup (it’s the ‘upsteam’ source where all of the team members commit), you need to make sure that you can always do a clean update from subversion. You want to avoid having subversion clobber your local changes and you definitely don’t want your use of git to clobber anything in subversion. To do this, hold fast to this simple rule in how to use the branches in git:

the git ‘master’ branch is a clean, stable subversion checkout

The git ‘master’ branch is almost always a clean checkout from subversion. It may not be up to date with the subversion server, but it is clean for whatever revision it is on. I very rarely work directly in the master branch, in git, actually. The only time I will work directly in the master branch is when I know I’m making a very small change that will be completed before my next food/drink/bathroom/whatever-else break. I do this so that I always have a known good copy of the subversion checkout. Without this, it’s very easy to get your git revisions out of sync with your subversion revisions, and cause problems when committing to subversion.

Really, it really doesn’t matter if its the master branch or not. It can be any branch you want – just make sure you have one that is a clean, stable checkout from subversion. I recommend using the master branch for this, though, as the significant of ‘master’ in git being correlated to the stable subversion checkout makes it a natural fit.

This is likely the most important rule in managing the interaction between git and subversion, though. The reasons will become apparent, later.

Just Another Git Repository

If the git ‘master’ branch is always a stable subversion checkout, then it follows that all work is done in a git branch (other than the master branch). With this in mind, we can fall back on the already known patterns of managing feature branches and managing a local git repository.

After getting your git+svn setup, branch off the master in git and start working. Other than the one rule about the master branch, you are managing a git repository like any other git repository. Branch, merge, rebase and do whatever else that you want to do with your local git repository. This is where the real flexibility of this process comes into play, honestly. You don’t have to worry about subversion very much because you are not dealing with subversion right now.

Committing Changes To Subversion

Once you have a set of changes ready to go and you’ll want to commit your changes to subversion. The first thing you need to do is update your master git branch with the latest changes from subversion. After that, you can merge your changes into the master branch and then commit to subversion.

Here’s how I manage this process:

1. Commit Or Stash In Git

Get all of your changes in your current git branch committed or stashed, and change your current branch back to master.

git add –A

git commit –m “some description of my changes”

</div> </div>

2. Update The Master Branch From Subversion

Once you’re in the master git branch, do an svn update. If you’re already working in a git bash prompt, you should be able to run ‘svn up’ from there and have it pull all the latest changes from the central subversion repository.

git checkout master

svn up

</div> </div>

3. Commit SVN Updates To Git

After you update from subversion, you need to commit the changes to your git repository. I typically comment the git commit with “update from svn” so that I know why all these files changed.

git add –A

git commit –m “update from svn”

</div> </div>

4. Merge Your Working Branch’s Changes Into ‘master’

Once you have all the latest and greatest changes from subversion, you can dump all of your working branch changes into the master branch. Remember that you’re dealing with git at this point – you have as many options as git provides for getting your working branch changes into your master branch.

This is the one time that I allow my master git branch to have any significant changes in it – but only because it’s temporary. After the working branch changes are in the master branch, I immediately move on to the next step.

git checkout myworkingbranch

git rebase master

git checkout master

git merge myworkingbranch

</div> </div>

5. Commit To Subversion

Now that you have your master git branch up to date in relation to subversion, with your git branch’s changes also in place, you can commit these changes to subversion. Be sure to add some descriptive comments of why you are making this commit (and remember – git / subversion will tell you what changed, it’s your job to say why you changed it.)

svn commit –m “some description of my changes”

</div> </div>

Lather, Rinse, Repeat

I don’t expect everyone to use this exact set of commands, though. I don’t even do it this way all the time, honestly. This is just one example of how you can manage the git+svn process. There are probably a dozen or more methods of managine your git+svn setup. I’m very interested in hearing about how you do it, too. Please drop a comment here or put up your own blog post on how you approach this situation.

But that’s all there is too it, really. The process is fairly straightforward and can be repeated as often as needed.

Benefits, Drawbacks, and Lessons Learned

There are a few things that I really like about this git+svn setup, a few things that bug me, and some lessons that I’ve learned as well.

All The Benefits Of Branch-Per-Feature, Lower Subversion Overhead

This is a complete branch-per-feature implementation running on an individual team member’s computer. All of the benefits (and drawbacks) that have been discussed around branch-per-feature are in play, here. The real benefit, though, is that you get branch-per-feature with a lowered subversion cost. You can quickly snap off branches from the git master branch, make changes, dump them back into master and commit to subversion – all while having another branch or ten sitting in the git repository, waiting for you to get back to them.

Don’t Worry About Keeping Up With Subversion Changes

Since you have the master branch in git stable, as a clean checkout of a subversion revision, you don’t need to keep updating it constantly. You can wait until you are ready to merge your changes into subversion and commit them. I’ve gone for several days (almost a week, once) without pulling down any updates from subversion, with no problems. This is one of the reasons why it’s important to keep your master branch as a clean, stable subversion checkout.

No More Subversion Merge Conflicts

I don’t have subversion merge conflicts anymore!!! WOO HOO!!! 🙂

Even when pulling down a significant amount of changes from subversion, I don’t have merge conflicts anymore. Once again, this is because the ‘master’ branch in git is a clean, stable checkout of the subversion repository.

You will still have merge conflicts, mind you – just not from subversion. Your changes in git are subject to the same rules and processes as any other git repository, though, and we all know that merge conflicts happen. Don’t fool yourself into thinking that you’ll never have a merge conflict again – that’s crazy talk.

Administrative Overhead

As I mentioned earlier in this post, there is an overhead associated with this git+svn setup. Specifically, the process of moving commits into the master branch so that they can be committed to subversion does add some more work. There are likely other things that add a bit of time, too. You need to evaluate this process (and potentially improve upon the steps I’ve outlined) for yourself to see if/when the cost is outweighed by the benefits.

One Git Repo Per SVN Checkout

When I first started out, I was managing git repositories in specific sub-folders of my subversion checkout. For example, we have a Trunk/Source/TA folder and a Trunk/Source/TAMobile folder, each of which contains a different solution. I originally set up a git repository in each of these folders thinking that it would be easier to manage them independently. This turned out to be a bad idea and a management headache. I had to wipe out my git repositories and recreate them more than once because I accidentally left them sitting in branches when I did an svn update. It took a few tries, but I finally learned the lesson: one git repository per svn checkout.

Your mileage may vary on this point, though. You might be able to manage multiple git repos in a single svn checkout – but I wouldn’t recommend it.

!!!Caveat Emptor!!!

Any time you mix and manage multiple source control systems manually, like this, you are opening up the possibilities of clobbering either or both of the systems. This is not a fool proof solution. There are no safeguards here. This is raw, high risk source code management. With such high risk, though, comes a very high potential for making your life easier. If you’re not comfortable with git or subversion (or worse yet, both) to the point where you know how to fix your mistakes without the assistance of others, then I would recommend that you not yet take on an endeavor as risky as this. Get comfortable with managing git and subversion, first.

A Step In The Right Direction, But Not The End Goal

I’ve been working with git+svn for more than 2 months now and I don’t know if I’ll go back to managing branches in Subversion – at least not for this team. I imagine there will be times when I need to do a push into a subversion branch for one reason or another, but this is likely going to be an exception to how I work now.

In the end, though, the git+svn setup is definitely not the goal. There are enough potential issues with it and there is enough of an administrative overhead, that is make me cringe at times. Ultimately, I would like to run git as the source control system for our team. But until that time arrives, I have a working solution for my needs.