How we got rid of the database

A quick introductory sample – Part 1

I want to write a series of posts which describe in detail how we do things in my company. What architecture do we use, which patterns do we follow, and more specifically, how do we implement those features. I invite you to join me on this journey…

Note: the core ideas follow the various examples of Greg Young, Rinat Abdullin, et al.

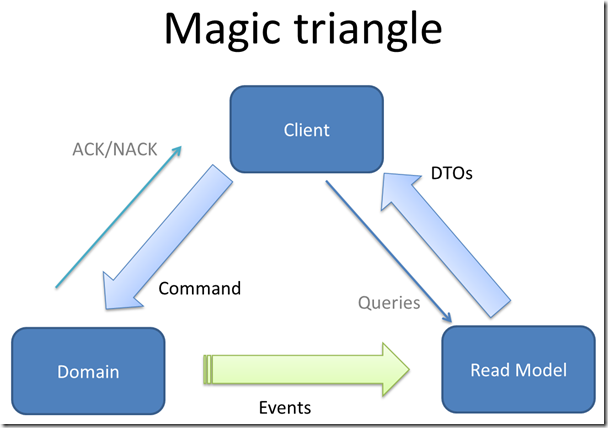

It all start with a simple picture

A similar image was used by Greg Young in his 6-hour video about DDD, CQRS and Event Sourcing. This image nicely shows us what is happening in an application following CQRS. The client sends commands to the domain (-model). The domain either accepts a command and hence sends ACK (=acknowledged) or refuses it altogether and sends a NACK (not acknowledged) back to the client. If the domain model accepts a command then it produces an event as a result of the execution of the command. The event is consumed by the read model. The read model in turn is used by the client to get its data in the form of DTOs.

Lets write some code to demonstrate how we do things. I will start from scratch, that is from a blank solution, and incrementally develop the code we need to fulfill the requirements.

But first we have to give a somewhat realistic user story to start with:

As a principal investigator I want to schedule a new task. The task has a group of animals as targets upon which the executor of the task acts. The task is addressed to a group of crew members from whom one can chose to execute the task…

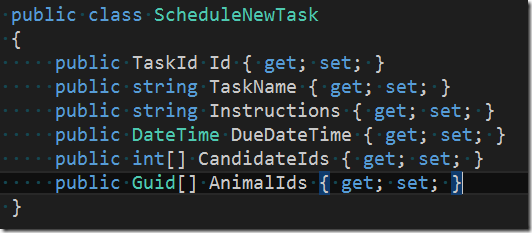

Evidently a user (= the principal investigator) wants to schedule a new task. This is done by the system by sending a command (ScheduleNewTask) to the domain. After discussion with the domain expert it is clear that the command should look like this

The name of the command gives us the context. From it it is clear what the intent is. The command name should thus be unambiguous.

The command is a DTO and its payload usually contains the minimal data necessary to successfully fulfill the request. In our case these are

- The (client side generated) unique ID of the new task. Note, that we do not just use a simple type for the ID like int or Guid but rather a class TaskId.

- The name of the task (in combination with the due date this should be unique)

- A description of what the executing person is supposed to do

- The date (and time) when the task is due

- A list of IDs of the candidates (staff) that can choose to accept (and execute) the task

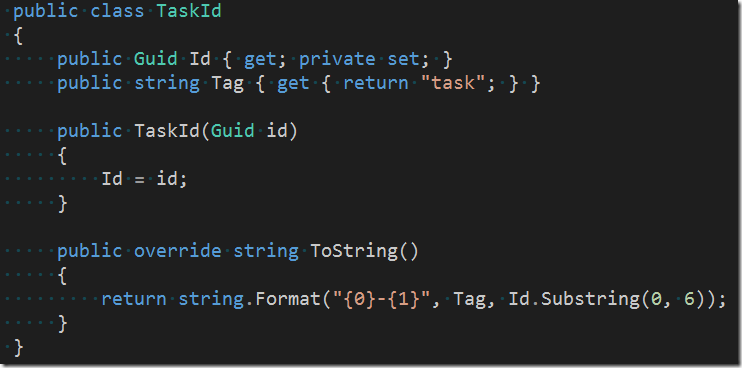

- A list of IDs of the animals which this task targets.</ul> Now let’s look a little bit closer at our ID. The code to is looks similar to this

Evidently the “real” id is of type Guid and there is also an associated Tag (=”task”). The tag is mainly used to output a human readable version of the id. For this purpose the ToString() method is overriden. Having an ID of type TaskId for a task and e.g. StaffId for a staff makes those IDs distinguishable. Has we only used Guids for both type of IDs we wouldn’t have been able to tell which one belongs to which type of entity.

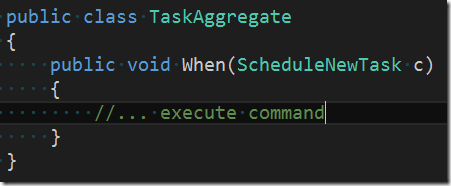

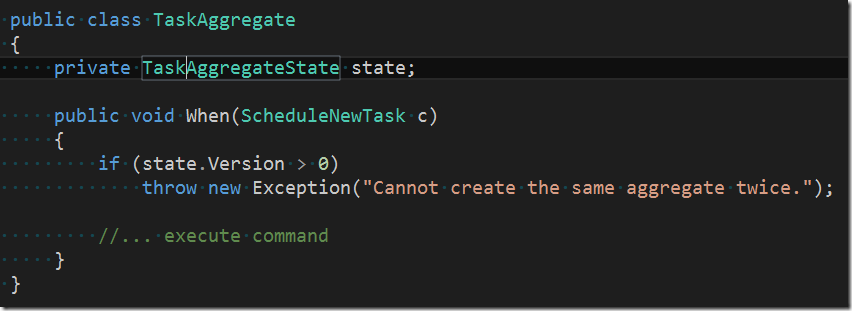

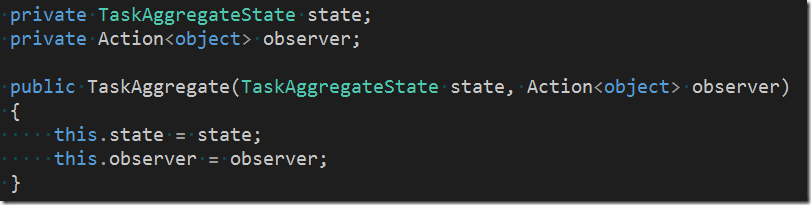

The command is targeting the domain. Inside the domain there is an aggregate which handles the command. We call this aggregate TaskAggregate.

To make things simple and discoverable we use some simple conventions. In the case of an aggregate we call the method who handles a command When and we always pass exactly one parameter to this method – the command itself. This results in very readable code (at least regarding the method signatures).

The method first makes sure that the command doesn’t violate the aggregate’s invariants, e.g. like this

In the above code snippet the aggregate uses its internal state to determine whether this command is the very first command (Version = 0) or not. If not then we have a problem since the system wants to re-create an already existing task instance; which of course we do not allow.

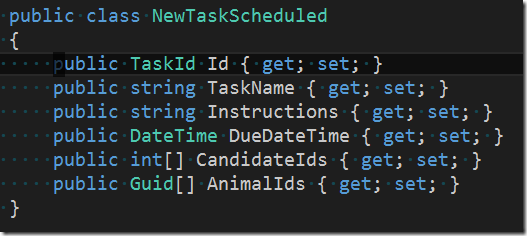

Once the invariants are guaranteed the aggregate transforms the command into an event. The event tells any observer(s) that the corresponding command has been successfully executed. The name of the event is in past tense, i.e.

In our case we have a one-to-one matching of the command’s payload with the event payload. This one-to-one matching is often the case but by no means the only possibility. Often an event can be enriched by additional data if needed by any observer.

It is very important that we always name our events in past tense. This makes it clear that an event is something that has already happened and cannot be undone!

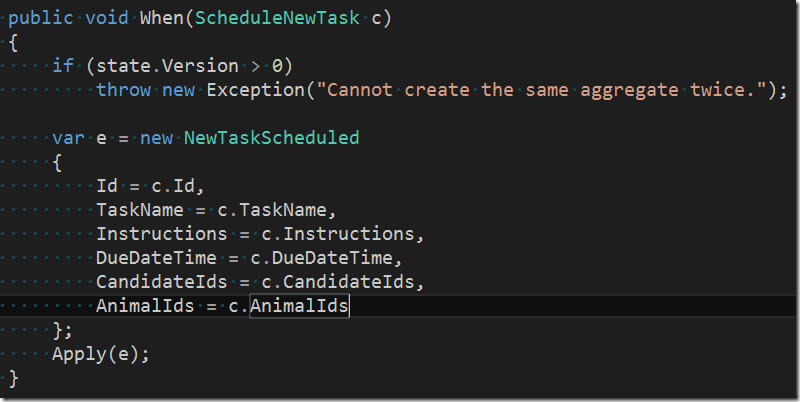

Now lets look again at the aggregate. We extend the method’s code as follows

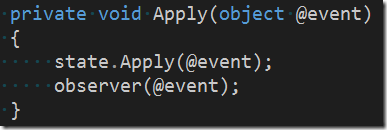

Note that once we have created the event from the command, we are call a private helper method Apply. The method Apply forwards the event to the aggregate’s state and also to an external observer

The initial aggregate state and the external observer are injected by the infrastructure into the aggregate at its creation time

The (external) observer injected by the infrastructure will take this event, store it in the event store and forward it to our queuing system which eventually will dispatch it asynchronously to any registered consumer of the event. Typical consumers are the writers who create and update the read model.

In part 2 we will discuss some more details about how events are stored in the event store. Till then, have a great time.

- A list of IDs of the candidates (staff) that can choose to accept (and execute) the task

- The date (and time) when the task is due

- A description of what the executing person is supposed to do

- The name of the task (in combination with the due date this should be unique)