Dependency Injection in ASP.NET MVC: Final Look

Other posts in this series:

In this series, we’ve looked on how we can go beyond the normal entry point for dependency injection in ASP.NET MVC (controllers), to achieve some very powerful results by extending DI to filters, action results and views. We also looked at using the modern IoC container feature of nested containers to provide injection of contextual items related to both the controller and the view.

In my experience, these types of techniques prove to be invaluable over and over again. However, not every framework I use is built for dependency injection through and through. That doesn’t stop me from getting it to work, in as many places as possible.

Why?

It’s really amazing how much your design changes once you remove the responsibility of locating dependencies from components. But instead of just talking about it, let’s take a closer look at the alternatives, from the ASP.NET MVC 2 source code itself.

ViewResult: Static Gateways

One of my big beefs with the design of the ActionResult concept is that there are two very distinct responsibilities going on here:

- Allow an action method to describe WHAT to do

- The behavior of HOW to do it

Controller actions are testable because of the ActionResult concept. I can return a ViewResult from a controller action method, and simply test its property values. Is the right view name chosen, etc.

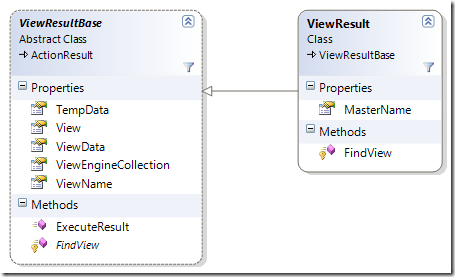

The difficulty comes in to play when it becomes harder to understand what is needed for the HOW versus the pieces describing the WHAT. From looking at this picture, can you tell me which is which?

Offhand, I have no idea. The ViewName member I’m familiar with, but what about MasterName in the ViewResult class? Then you have a “FindView” method, which seems like a rather important method. The other pieces are all mutable, that is, read and write. Poring over the source code, none of these describe the WHAT, that’s just the ViewName and MasterName. Those are the pieces the ViewEngineCollection uses to find a view.

Then you have the View property which can EITHER be set in a controller action, or is dynamically found by looking at the ViewEngineCollection. So let’s look at that property on the ViewResultBase class:

[SuppressMessage("Microsoft.Usage", "CA2227:CollectionPropertiesShouldBeReadOnly", Justification = "This entire type is meant to be mutable.")] public ViewEngineCollection ViewEngineCollection { get { return _viewEngineCollection ?? ViewEngines.Engines; } set { _viewEngineCollection = value; } }

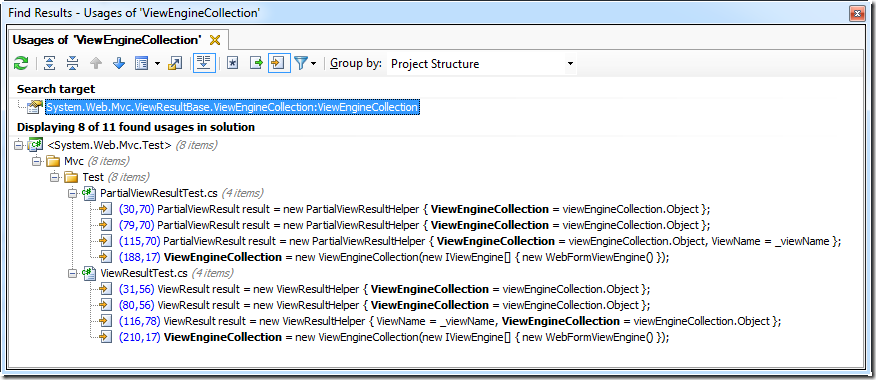

Notice the static gateway piece. I’m either returning the internal field, OR, if that’s null, a static gateway to a “well-known” location. Well-known, that is, if you look at the source code of MVC, because otherwise, you won’t really know where this value can come from.

So why this dual behavior?

Let’s see where the setter is used:

The setter is used only in tests. All this extra code to expose a property, this null coalescing behavior for the static gateway (referenced in 7 other places), all just for testability. Testing is supposed to IMPROVE design, not make it more complicated and confusing!

I see this quite a lot in the MVC codebase. Dual responsibilities, exposition of external services through lazy-loaded properties and static gateways. It’s a lot of code to support this role of exposing things JUST for testability’s sake, but is not actually used under the normal execution flow.

So what you wind up happening is a single class that can’t really make up its mind on what story it’s telling me. I see a bunch of things that seem to help it find a view (ViewName, MasterName), as well as the ability to just supply a view directly (the View property). I also see exposing through properties things I shouldn’t set in a controller action. I can swap out the entire ViewEngineCollection for something else, but really, is that what I would ever want to do? You have pieces exposed at several different conceptual levels, without a very clear idea on how the end result will turn out.

How can we make this different?

###

Separating the concerns

First, let’s separate the concepts of “I want to display a view, and HERE IT IS” versus “I want to display a view, and here’s its name”. There are also some redundant pieces that tend to muddy the waters. If we look at the actual work being done to render a view, the amount of information actually needed becomes quite small:

public class NamedViewResult : IActionMethodResult { public string ViewName { get; private set; } public string MasterName { get; private set; } public NamedViewResult(string viewName, string masterName) { ViewName = viewName; MasterName = masterName; } } public class ExplicitViewResult : IActionMethodResult { public IView View { get; private set; } public ExplicitViewResult(IView view) { View = view; } }

Already we see much smaller, much more targeted classes. And if I returned one of these from a controller action, there’s absolutely zero ambiguity on what these class’s responsibilities are. They merely describe what to do, but it’s something else that does the work. Looking at the invoker that handles this request, we wind up with a signature that now looks something like:

public class NamedViewResultInvoker : IActionResultInvoker<NamedViewResult> { private readonly RouteData _routeData; private readonly ViewEngineCollection _viewEngines; public NamedViewResultInvoker(RouteData routeData, ViewEngineCollection viewEngines) { _routeData = routeData; _viewEngines = viewEngines; } public void Invoke(NamedViewResult actionMethodResult) { // Use action method result // and the view engines to render a view

Note that we only use the pieces we need to use. We don’t pass around context objects, whether they’re needed or not. Instead, we depend only on the pieces actually used. I’ll leave the implementation alone as-is, since any more improvements would require creation of more fine-grained interfaces.

What’s interesting here is that I can control how the ViewEngineCollection is built, however I need it built. Because I can now use my container to build up the view engine collection, I can do things like build the list dynamically per request, instead of the singleton manner it is now. I could of course build a singleton instance, but it’s now my choice.

The other nice side effect here is that my invokers start to have much finer-grained interfaces. You know exactly what this class’s responsibilities are simply by looking at its interface. You can see what it does and what it uses. With broad interfaces like ControllerContext, it’s not entirely clear what is used, and why.

For example, the underlying ViewResultBase only uses a small fraction of ControllerContext object, but how would you know? Only by investigating the underlying code.

New Design Guidelines

I think a lot of the design issues I run into in my MVC spelunking excursions could be solved by:

- Close attention to SOLID design

- Following the Tell, Don’t Ask principle

- Favoring composition over inheritance

- Favoring fine-grained interfaces

So why doesn’t everyone just do this? Because design is hard. I still have a long ways to go, as my current AutoMapper configuration API rework has shown me. However, I do feel that careful practice of driving design through behavioral specifications realized in code (AKA, BDD) goes the farthest to achieving good, flexible, clear design.