Eventual consistency, CQRS and interaction design

Gabriel Schenker’s excellent series of posts on “How we got rid of the database” offers a great insight on the benefits of a CQRS/ES application. One of the problems often seen with designing user interfaces that introduce eventual consistency into the mix is how to present this new paradigm to the end user. But whether we’ve thought or not, eventual consistency is all around us, as Gabriel points out in a few examples:

- Ordering a book online, dealing with stock

- Unit price of a stock changing

- Ordering coffee where the barista starts making the coffee before your payment is complete

- Organizing care during an accident (a little morbid)

In all of these situations, the user is dealing with more than one agent/service boundary. There is already an expectation on the user side that there needs to be coordination involved.

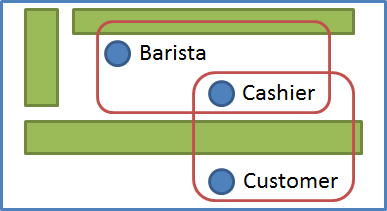

In the human examples, coffee shop for example, the barista and the cashier, we have an interaction with the cashier/customer, and an interaction with the cashier/barista:

Transactionally, I have one transaction between the cashier and customer (place the order) and one transaction between the barista and the cashier (make the order).

Looking at eventual consistency, it’s between these two transactions/interactions that we have eventual consistency. But inside each transaction, it either succeeds or fails, and does so synchronously. I don’t hand the cashier my credit card and go run an errand to come back later. I stand at the cash register, waiting, until my payment succeeds.

If it succeeds, my order is confirmed. If it fails, the cashier issues a compensating action to the barista to say “toss that order in the bin”.

Eventual consistency in interaction design

Translating the above to a UI, making the order is behind the scenes, but paying for the order certainly is synchronous. The user expects (for this small transaction) that they pay, and the order is complete. There is no recourse during payment for “emailing the customer” or yelling out their name on the store PA to please come back and pay. It is not a fire-and-forget message or a fire-and-wait-perhaps-it-most-likely-succeeds message. It is a “pay now or your order is cancelled” message.

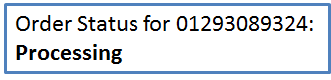

Users are smart. For interactions that they expect to be fire-and-forget (like the ecommerce example), we can shape our interactions to more closely mold what is actually happening, and the user will not complain. For example, in Amazon, placing an order is synchronous, but fulfilling your order is not. How do they accomplish this in the UI?

On the confirmation page after submitting an order (which is most definitely synchronous), it’s clear that what we are submitting is an order request. An order request to be fulfilled later. If things go wrong, we’ll have other means to fix the order through offline means, but we’ve already set the user expectation through simple statuses that “this is behind the counter stuff”.

But this is expected because the user is interacting with multiple agents. Eventual consistency is an obvious result of interactions between multiple humans and between services.

What about a single, event-sourced application?

Communicating intent

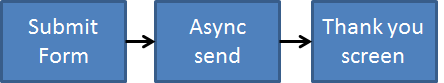

In many event-sourced applications I see, the interaction is something like:

This can work well if the user already expects the submission to be a “request” that may or may not fail. We might up the probability of it succeeding by pre-validating. But if no one else is using my aggregate, why might the command fail in the back end? It probably shouldn’t but now we’ve just put a wacky interaction on top of the user where it’s not needed.

Looking at a single aggregate, commands can fail when the aggregate has changed. Aggregates can change when other people are interacting with it, which can be a fairly low occurrence. If the occasions of multiple people working on the same aggregate instance is low, why do an async command at all?

Instead, you can do a synchronous execution against the aggregate and an async update to the view models.

But back to that pesky problem of users waiting to have the view model updated. If you have users that have to wait to have the view model updated to see their results, you have built the wrong user interface. Results should be immediate. Did you receive my command or not? Yes or no? What is the status of my command? This is the interaction you should have.

And if the user doesn’t think like this with their interaction and information, then you’ve picked an eventually consistent model that doesn’t apply.

Eventual consistency arises in interactions between service boundaries. It’s much more rare inside service boundaries.

If you slap on eventual consistency on places where it wasn’t before or isn’t obvious that it’s needed/necessary to users, get ready to do some parlor tricks to create the illusion of immediate consistency.