Saga implementation patterns – Observer

NServiceBus sagas, itself an implementation of the Process Manager pattern, often takes one of two main forms when implemented. It’s not a cut and dry distinction, but in general, I’ve found that saga implementations typically fall into one or the other.

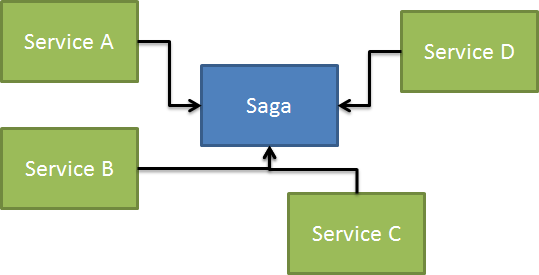

The first kind would be the Observer pattern. As an Observer, this saga responds to events to coordinate an activity:

There are a few characteristics of the observer:

- Messages are received as events

- The Saga does not control the order in which messages are received

Since the Saga does not control message ordering and these messages are events, the saga behaves as an observer. It doesn’t influence these external services, but instead observes results through event each publishes.

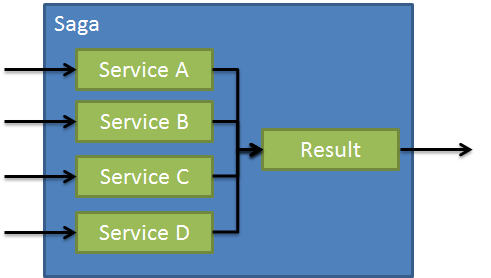

Another interesting characteristic of an Observer saga is that typically, its purpose is to coordinate some activity after it has received all service events. It begins to look something like this:

This is similar to the Scatter/Gather pattern, but not quite. The saga itself often needs to keep track of which messages are received. Upon receiving a message, it will note that the message has been received, and check to see if all relevant messages have been received before proceeding onwards.

It’s a simple workflow pattern, with the caveat that it doesn’t know which messages will be received in which order.

To see this in action, let’s look at a real-world scenario where we can observe this pattern in play.

Fast food messaging – McDonald’s

The fun thing about learning distributed systems is that the examples of application are literally all around us. One great example of the saga observer pattern in actual real-world use is the fast food chain McDonald’s in-store ordering process.

Order preparation in McDonald’s (and many other fast food chains) is not a linear process. There are a number of stations performing work, but they do so relatively independently. In any given order, we might have:

- Sandwiches

- Drinks

- Salads

- Fries

- Coffee

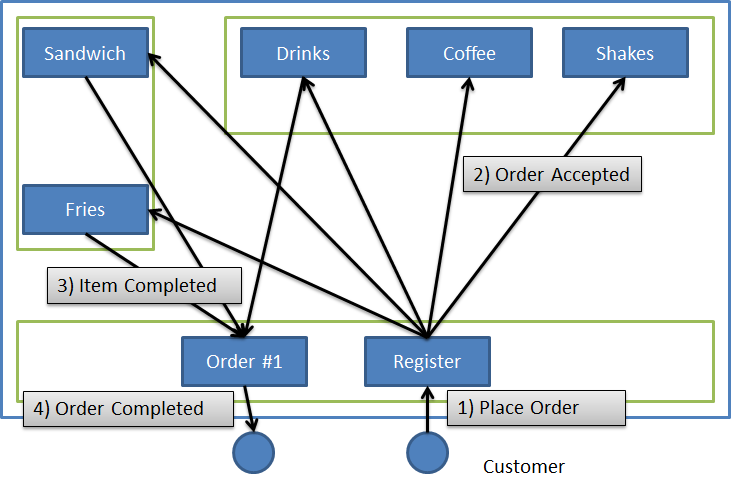

And so on. Each station is its own independent worker, with its own independent queue of work. A typical order looks something like this:

The order starts off with a customer placing an order (1). If the order is accepted (they have money), then an event is broadcasted to all relevant food preparation stations (2). Each station has a computer screen above it, representing a queue of work to be done.

Only the relevant orders show up on the relevant screens. If the order has no fries, the fry station screen does not show anything with that order.

Each station does its work independently of the other. The fry station doesn’t need information from the drink station to do its work.

As each station completes the order, they take the food back to the counter (3) – where each order to be delivered is separated by a food tray. Each station is responsible for figuring out which tray their food belongs to – correlated by the order number. On each station’s screen, orders are separated out by order number so that each station has some information to correlate a single order.

Each time a station brings a completed item to the tray, the employee checks the receipt on the tray to determine if the order is completed. This is done with each item brought to the tray, we must re-check the items to see if the order is completed. There is not one person in charge of this responsibility – every employee bringing finished items does this check.

Once an employee determines that the order is complete, they call out the order number and the original customer picks up their tray (4).

Well before sagas were implemented in NServiceBus, we had observer sagas in real life (though we never called it this).

Benefits and drawbacks

This pattern, like all others, has some benefits and drawbacks. McDonald’s implemented this pattern to maximize the efficiency of processing orders, but it’s not a universal pattern in fast food chains. The benefits include:

- Each worker operates in parallel with others, upping the overall throughput

- Each worker is independent of others, and is decoupled from other steps

- We can add additional steps and workers fairly easily (McDonald’s added coffee recently, but this didn’t change their overall order delivery pattern)

However, this pattern is not without its drawbacks:

- Resource contention is introduced. We can’t have two employees delivering food to the same tray at the same time – there’s just not physical room for them! The tray/saga becomes the choke point in our system – and this piece we can’t easily scale

- Every step has to check to see if the saga is complete. This introduces extra logic to our saga to keep track of what’s done, and check to see if it’s complete

Next time you go to a fast food restaurant, see if they fulfill their orders this way. In a restaurant with highly independent steps, they’ve likely determined that this method of managing orders is most efficient.

However, it’s not always the best way. In the next post, we’ll look at the converse of the observer – the controller.