Curbing long tail design

One of the perks of my job (and talking to a lot of folks) is that I get to see a lot of people’s actual code. Not gists, blog examples, or GitHub playgrounds, but real, actual, production code. Some code is good, some bad, and some awful. What is universal is that everyone thinks that everything sucks.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Often times, the reasons the codebase lost its way was not because any one piece is awful, but the overall design lacks any sort of cohesiveness.

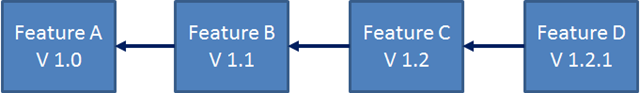

Instead of having one design, the codebase has many competing designs. Whenever a developer adds a new feature, they have to hunt for the last “good” feature. Design follows a long road:

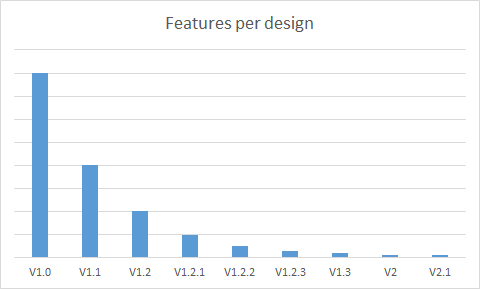

We start out with the first few features as V1.0 of the design and architecture. As we learn more, we augment our design to V1.1. Many more features are added with this design, until we make another breakthrough in the design with V1.2. One developer read something cool on a blog, augmented the design in one spot, and now we have V1.2.1. It continues along this path until we have a long tail design:

A new developer coming to this team has no chance! There are many problems with evolving a system this way.

First, we don’t really know what the “right” design is. If we need to augment an old feature, is that the “right” design? Do we just pick the last new feature built, and copy that design for our next new feature?

Second, the ability to innovate in our designs really comes from having a broad view of the system. If I have eight different ways of doing something, I can’t really innovate. If I had many examples of a design in use, it’s a lot easier to see where the design works well, where it doesn’t, and what needs to change. Long-tail designs stagnate because we lose that opportunity to see the design in use across the entire system.

It’s an absolutely insidious problem. Many times when developer complain about messy code, it’s really because of a lack of consistency in the design. Adding a new feature to a system should require a reassessment or CSI investigation into the current architecture. Design should be boring, refactoring is where the fun comes in. But fun takes discipline, and so does an evolutionary design.

Law of two

A system should either have one consistent design, or two designs, the previous and the next design. As you look at a number of features with one design, you’ll gain an insight and want to try out a new design. But this is where things get tricky – you’ll actually need to try out the design to see if it works. And that design might take several tries to get right.

Instead of allowing more and more features to iterate over the previous design, which leads to long-tail design, you’ll instead only allow at most two designs in your system. Before doing any more innovation on your new design, move all the existing features to the new design. If you’re working in small steps, this shouldn’t be much of a problem. If the design is a little more involved, it might take a month or two of incremental work to move your features over.

What I’ve found is that my designs tend to get much better the more examples I have to work with. By only allowing at most two designs, I can maximize the potential of my next innovation. But with many competing designs, it dilutes my design, and I have a lot harder time seeing what my next step should be.

Evolutionary design and architecture is hard, but hard more from a discipline stance. You have to be disciplined not to “outrun your supply line” with your design. It can be a bit frustrating, you KNOW the next step to take, but in the end, it’s just not worth the risk of having the long-tail design.