Domain Modeling Around Deletes or “Using Cassandra as a queue even when you know better”

Understanding Deletes

Delete heavy workloads have a number of pretty serious issues when it comes to using a distributed database. Unfortunately one of the most common delete heavy workloads and the most common desired use case for Cassandra is to use it as a global queue. This blog post is aimed at addressing the queue anti-pattern primarily, but could be modeled for other delete heavy use cases.

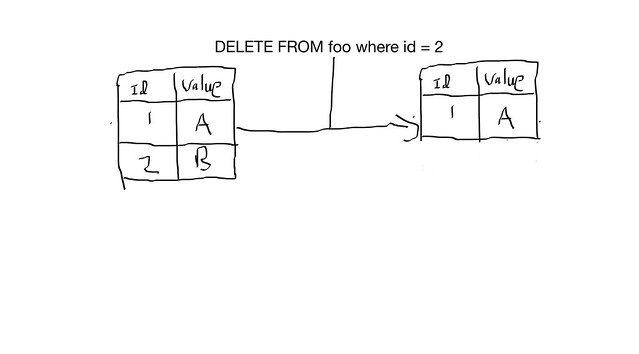

Why this is problematic we need to lay some groundwork and explain lets discuss the problems with deletes when no single machine is considered authoritative as in a truly distributed system. You may be thinking “Deletes on a single machine are easy, you add a record, you delete the record and immediately get disk space back”, something like the following:

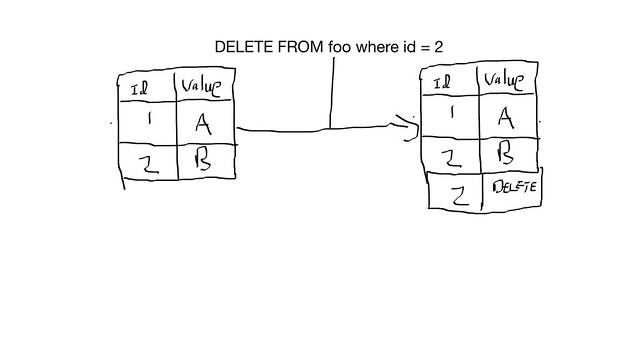

In Cassandra, because it’s distributed we actually have to WRITE a marker called a ‘Tombstone’ that indicates the record is deleted.

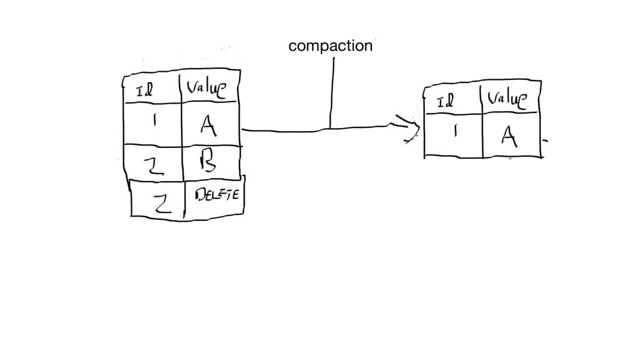

Why is this? Because imagine a scenario with 3 machines that own the same record. Now you maybe thinking “how do I ever reclaim disk space if all my records never go away, in fact I use up more space by deleting?”. The developers of the Cassandra project got you covered, and there is a time period which defaults to 10 days where 10 days after a delete is issued the tombstone and all records related to that tombstone are removed from the system, this reclaims diskspace (the setting is called gc_grace_seconds). You realize that based on your queue workflow instead of 5 records you’ll end up with millions and millions per day for your short lived queue, your query times end up missing SLA and you realize this won’t work for your tiny cluster. So you think “Why 10 days? Why not 1 minute? Why not right away?” So you set gc_grace_seconds to 0. Now as soon as the next compaction occurs on a given node, it will remove that record and it’s tombstones.

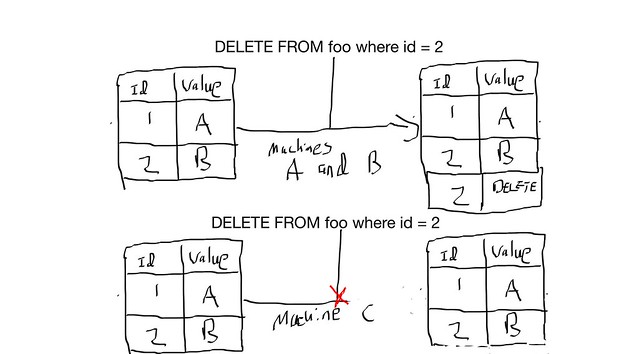

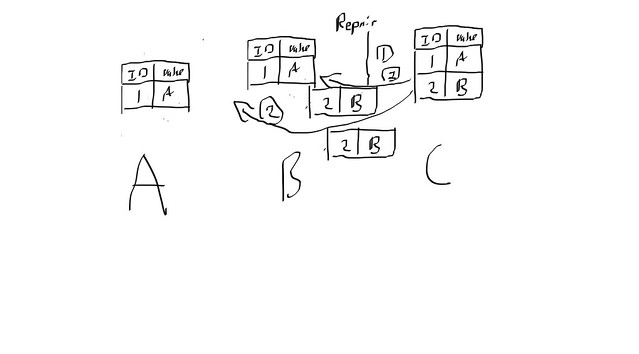

Let’s assume you go ahead and set the gc_grace_seconds to 0, this seems to work and everyone is happy. Your developers have their queue now. Now let’s say one machine loses it’s network card and writes start failing to it. This is no problem at all as you’ve done your homework and set the replication factor to 3 so that 3 machines own the record. When you issue your delete the 2 remaining machines happily accept it. In the meantime you find a network card, and you don’t want to bother with decommissioning the node in the meantime (the cluster seems to not miss it to to badly, why is for another blog post). Once you put the network card back in and start the node you get an angry phone call from a developer who says the Cassandra cluster is broken and that jobs that were already processed are firing again. What happened? This is best illustrated below:

Machines A, B had their records with this job removed, Machine C which has a record of this job but because gc_grace_seconds was 0 A and B have no tombstones or record of this job ever being executed, so when doing any repair Machine C replicates this new/old record back over and whatever process is looking for new jobs fires again on the already executed job.

So now we know setting gc_grace_seconds to low creates a number of problems where records can “come back from the dead”, but we’re really set on using cassandra as our queue, what are the practical workarounds? Most of them revolve around the use of truncate.

Truncate

TRUNCATE foo;

Truncate removes all records on all nodes that have records in a given SSTable. This effectively will remove tombstones when you say it’s time to remove tombstones (all other records of course), but this gives us a useful tool when combined with domain modeling to manage tombstones effectively.

Partition tables based on domain modeling

Make 1 table per unit of work.

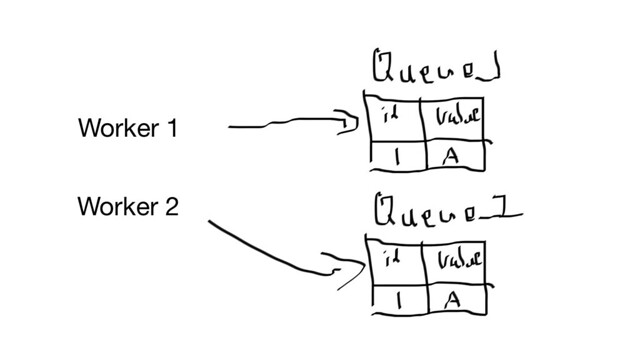

Lets say you have only a limited number of workers at a given time, you can say assign them an id and create tables based on this id, when the worker is done with it’s work, truncate the table. Something like

This approach really boils down to thinking about what are the unique non contentious units of work in your system and model them accordingly so that there is no overlap and your work is completed in small manageable chunks. If you have a large stack of work to do, say in the hundreds of millions that has to be done quickly, this may mean in the hundreds of tables to make this work.

Pros

- Easy to reason about

- keeps tombstones to a minimum

- ops per second instead of data density is the primary sizing component.

- Minimizes or eliminates race conditions depending on how the code is structured.

Cons

- Schema operations need all nodes to agree, so not cheap, should be infrequent enough to be not costly.

- Have to still be aware operationally, offline nodes that are brought back in without having data wiped or repaired appropriately can bring tables back from the dead.

- What do you do if the drop table fails? Have to handle this eventually with code and ops. A successful truncate should still save you if you’d done this correctly.

Partition tables based on a time event

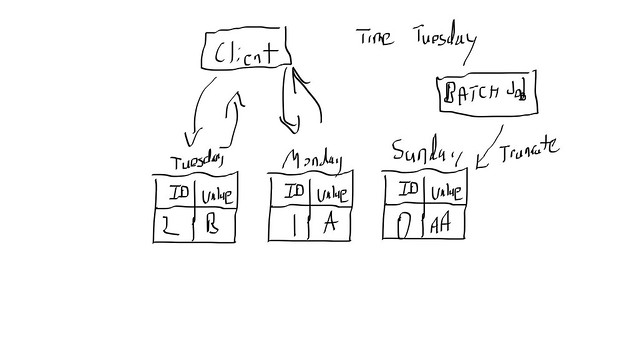

For time series, or global queues shared by several workers the domain modeling approach may not work as well. For those events I use the less optimal but still effective time based queues. The basic idea is size your tables around your desired size and time. Lets say I only need to query the last 2 days of data, if I create tables by day and make the clients aware of the this, it it’s Tuesday I can safely query data from Monday and Tuesday and then truncate all data from Sunday.

Pros

- Only runtime schema like operation is truncate. No table creation or removal.

- Domain modeling stays effectively the same. Code doesn’t change a lot.

Cons

- Time bugs suck more.

- Have to code more time based logic.

- Queries are up to 2x slower ( you are querying via async to minimize this right? ).

- Requires retaining more data than domain modeling based approach.

- Can have race conditions where you have different clients getting different answers at the interchange of time periods. Also make sure you only truncate with a time window that will make sense say 5 minutes to allow for some clock skew on clients.

- Because of the race condition possibility you may want to use Light Weight Transactions on updates and the appropriate SERIAL level consistency on reads. This will have performance implications, but it maybe worth it depending on needs.

- Your clients are more time sensitive. With the domain modeling approach you don’t have to keep your clients clocks in sync (though you should since you’re a good sysadmin anyway).

Some general things to watch out for

- Querying too many tables at once can get expensive itself so be mindful of this with SLAs

- There is in general a cluster max effectively limit on table counts. Anything over 300 starts to create significant heap pressure.

- Truncate takes a long time to run and effectively requires agreement from all nodes, be mindful of this on your performance guarantees and when you initiate a truncate that you’re not waiting. Also offline nodes can come back from the dead and add data back. So be mindful of your data model and when you truncate, make sure you have your ops team monitoring offline nodes.