Kanban in Software Development. Part 2: Completing the Kanban Board with Queues, Order Points and Limits

</p>

In Part 1 of Kanban in Software Development, I introduced the concepts of kanban boards and pipelines. I also showed a very simple example of creating a pipeline for our development process. However, there were some obvious limitations in what I showed. The reality of software development is much more complicated than three simple steps (Analysis, Development and Testing). A software development team or company is going to have more to do than just these things, and there is usually a need for some team members to be cross-functional. Some team members will have to do development and testing, or analysis and development, or documentation and delivery, or any other combination of steps involved in creating software. In this post, I’ll address these issues, creating a more complete pipeline and finishing our kanban board.

Working In A More Complete Pipeline

To create a more complete kanban board, we need more than just a three step pipeline. We need to allow for a fully functional team – developers, analysts, testers, technical writers, and others. We also need to allow the different team members to work on different parts of the system, as work is needed. The end goal is to enable the system to flow through the process and to ensure the work is “done done” before it goes to the customers.

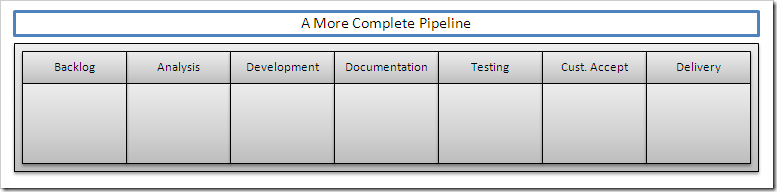

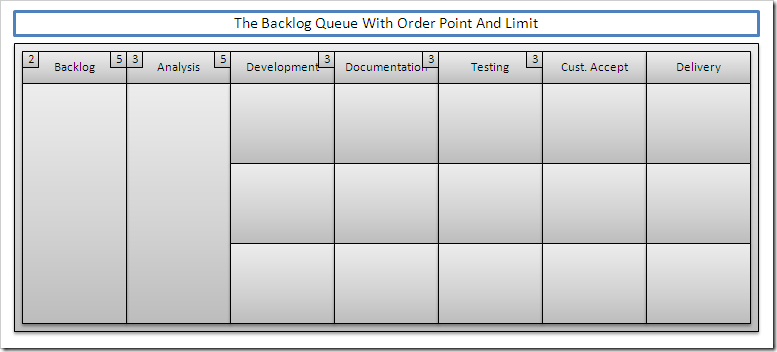

For a more complete software development pipeline, let’s use the following columns: Backlog, Analysis, Development, Documentation, Testing, Customer Acceptance, and Delivery. We can put together a pipeline diagram that follows these steps.

Now, let’s assume that we have the following team (ignoring project managers, customer representatives, etc, for now): 6 developers, 2 business analysts, 3 test automation engineers, and 3 technical writers. Given this team, we would not be able to make a feature flow through this pipeline. We would have developers sitting around, waiting for work from the analysts. And, our documentation writers and test lab people would probably be pulling his hair out from boredom then pulling their hair out from too much work, in an unbreakable cycle.

Fortunately, we can account for the team makeup and the potential bottlenecks by introducing the concept of order points and limits that we saw in the grocery store, and by creating queues and multiple pipelines to be worked.

The Real World – Multiple Pipelines and Limits

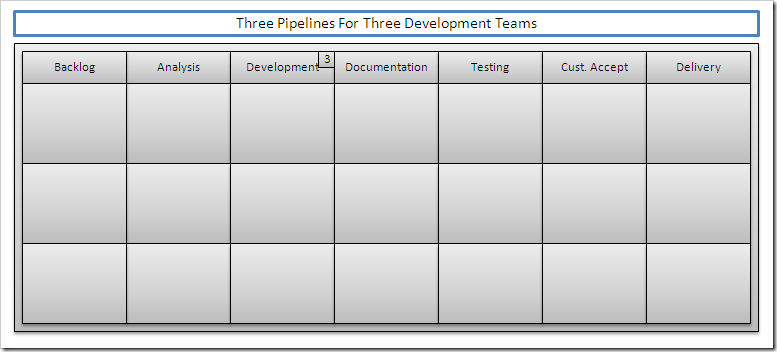

In most software development efforts, it’s unreasonable to expect an entire team to work on only one feature at a time. Most development managers want to maximize the throughput of development by working on tasks in parallel. Given this desire, we’ll divide up our developers into three teams of two developers each. This development team division should allow three features to be developed at the same time. Since we want to work on three features at a time, we will need three pipelines for work.

These three pipelines constitute our first limit – we can have a maximum of three features in development at any given time. This limit is noted by putting a “3” in the upper right hand corner of the development column header, as shown above.

Having three development pipelines puts us in a tricky situation, though. We have very few business analysts compared to developers – even with our developer teams, we have less than one analyst per developer team. Fortunately, development work often takes longer than analysis. We can use this knowledge to our advantage and let the analysts work slightly ahead of the developers, creating a queue of work to be done.

Handling Bottlenecks – Queues, Limits and Order Points

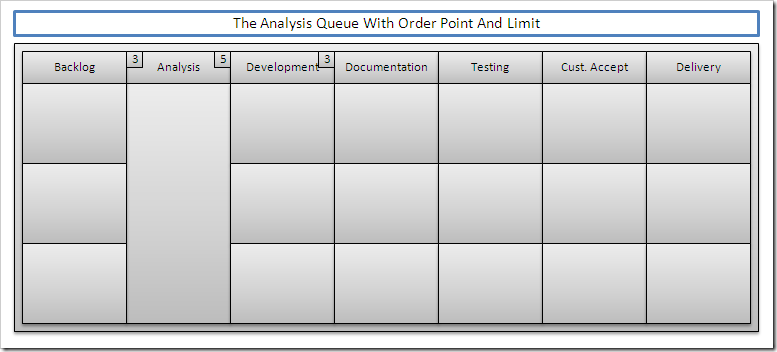

If all three development teams happen to finish at the same time and need more work, we would need a minimum of three features that are ready to be worked. However, since we know that requirements change regularly, we don’t want to get too far ahead of the developers. With this in mind, we can introduce an Analysis order point of three (the number of development teams) and limit of five. This gives the analysts the ability to work ahead of the developers and also makes them responsible for keeping work available for developers.

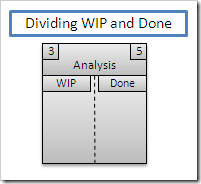

For an order point we’ll introduce the number into the upper left hand corner of a column header, and we’ll continue using the upper right hand corner to specify our limits.

Since we are now dealing with potentially more work in analysis than development, it seems we would have to increase our pipelines to five. This is not desirable, though, since we only have three development teams. What we will do, instead, is restructure the pipeline and turn the analysis column into a queue.

Since Analysis is now a queue, there does not seems to be a need for Backlog to be a step in a pipeline, either. The backlog is simply the list of features that the customer is expecting to be done next. Therefore, we will also turn the backlog into a queue – this time, with a priority (top of the board is highest priority) allowing the customer to tell us which specific feature should be worked on next. We will also want to keep the backlog column limited, to prevent the team from having too much information to think about. Since we only have two analysts on our team, it seems appropriate to keep at least two features in the backlog column at all times. With this in mind, we can safely set a backlog order point of two and limit of five (enough to keep the analysis column full).

The changing of Backlog into a queue has no made our Development column the first step in our actual pipeline.

Completing The Pipeline – Aggregate Limits and Work Cells

The next few column – Documentation and Testing – both have an easy amount of team members to deal with. There are three technical writers on our team, and three testing personnel. This distribution lets us keep the pipeline in tact between Development, Documentation and Testing, allowing us to set the same limit as Development (three).

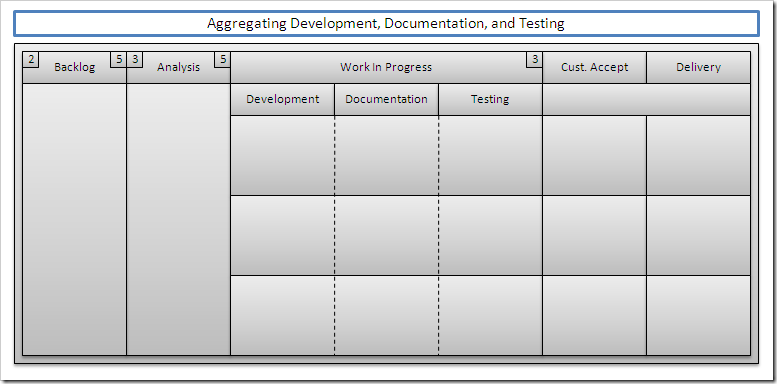

With all three of these columns having the same limits, and with each column being properly staffed so that three pipelines could run at the same time, it makes sense to combine the team members from these three columns into a single workcell. If we consider all four team members (2 developers, 1 tech writer, 1 tester) as a team and allow them to work together as a team, we can aggregate the limits of the columns in the pipeline. We can also create a consolidated name for this pipeline – work in progress.

This consolidation can be shown by creating a parent / child header with the limit shown in the parent. We will also use a dashed lines between the columns of the pipelines. The combination of these two details will show us that we are dealing with a pipeline, and how many pipelines are allowed to flow, simultaneously.

By aggregating the pipeline limits, we allow the workcell for a given feature to focus exclusively on that feature. The development staff, technical writers, and test lab personnel will all be working on the same feature, allowing them to more easily share information between themselves. This will prevent the team members from having to switch back and forth between subjects, reducing cognitive load and allowing for greater quality to be attained in the individual feature.

Completing The Kanban Board – Customer Acceptance and Delivery

If the customer is on-site (co-located with the team or close enough to meet every day), then it may be possible to aggregate the Customer Acceptance process into the Work In Progress pipeline. If you can do this, you should. Getting immediate feedback from the customer, while work is still fresh in you mind, is critical to the quality and success of that work. What’s more – you may not need this explicit column if you have the customer working with you every day.

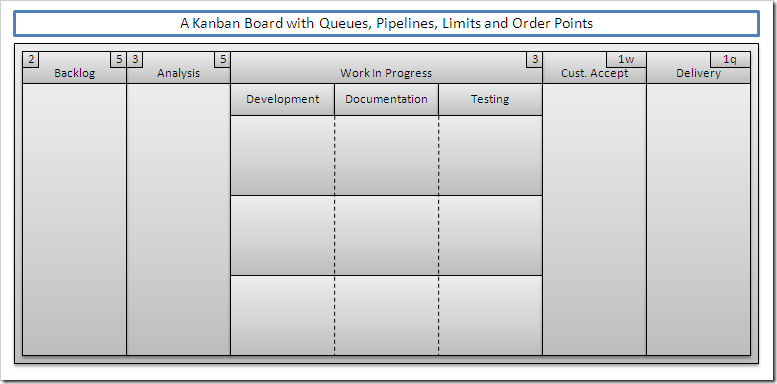

Unfortunately, we don’t always have the luxury of on-site customers. We may only have the customer around at specific timer intervals or only on request. In either of these cases, we have to account for the bottleneck of Customer Acceptance. Additionally, the customer may not want to get delivery of individual features. They may want to wait for a quarterly release, or some other regularly scheduled release. Once again, we have to account for this bottleneck. We can apply the same principles that we used for Backlog and Analysis here, and create some appropriate order points limits.

Let’s say that our customer wants to do Customer Acceptance testing once a week and wants a Delivery once every calendar quarter. To accommodate this, we can set the Customer Acceptance column as a queue with a 1 week limit. We can also set the Delivery column as a queue with a 1 quarter limit. Setting these limits puts a direct responsibility on the customer. If they cannot pull the features through these columns on or before the specified limits, then the entire system could grind to a halt. It’s important to educate the customer in what they are committing to, and ensure that they can fulfill their obligations. This fulfillment may mean that they assign more than one person or group of people to the task of Customer Acceptance and accepting Delivery. Whatever the solution is, the customer has responsibilities to meet.

With Customer Acceptance and Delivery specified, our completed kanban board would look like this:

Put It In Action – A Kanban Process Is Never Truly “Complete”

Now that we have clearly defined our Kanban process and visualized it through our Kanban board, the next steps is to start using it! Start working through this process, pull value from the end of the process and allow work to flow through the pipeline. Respect the order points and limits, and above all, look for problems in the process and fix the process when you need to.

Perhaps you have too few or too many items in one of your queues – adjust the limits and order points. Perhaps the test lab is now a bottleneck – take them out of the pipeline and change them to a queue. There are many possible problems and many possible solutions. The key is to be aware – inspect and adapt and hold regular retrospectives – kaizen your process and continuously improve.

Where Do We Go From Here?

No process is perfect. Anyone that tells you otherwise is selling something. A customer may find a bug during Customer Acceptance; an issue makes it past all of our QA processes and is found out in production; or there’s a feature that has a sudden priority over any other feature currently being worked. But our current kanban process doesn’t address the natural problems that occur during a software package’s lifetime. To address this properly, we’ll need to employ the lean tools of Andon and Jidoka, and we’ll also need to decide how to visualize this on our kanban board. These issues, and possibly more, will be addressed in another installment of Kanban in Software Development.