Branch-Per-Feature Source Control. Part 1: Why

Several years ago, I started using source control systems to store all of my code. It was a life saver. I was no longer worried about losing changes that I had made. Then a few years ago, I found Subversion. It was a god-send compared to visual source safe. The feature set was very nice, TortoiseSVN was easy to use, and I eventually found VisualSVN which made life even easier. My team(s) quickly picked up on Subversion and we were very, very happy. We even started using some continuous integration processes to ensure our code built correctly, etc.

How We Used To Work

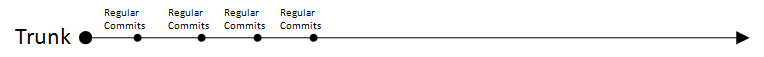

The way that my team worked, at the time, was based on the industry standard of “Branches”, “Tags”, “Trunk” for the high level organization. I’m honestly not sure if the industry standard is to have everyone working on the trunk, but that is what we standardized on. All live software development processes were done on the trunk, no matter the size of the team. This meant that there were multiple commits from multiple people, multiple times per day, all on the trunk.

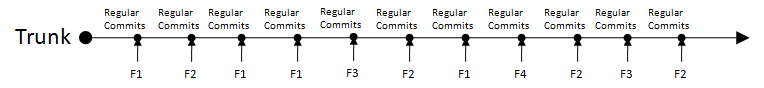

This worked fine for a very long time. Especially when we looked back at having no source control. The easy to use svn applications made life good, and no one seemed to mind that everyone was committing to the trunk all the time. It really didn’t matter what feature a person was working on, because we tended to work in horizontal layers of the application. This meant that there would be, in any given period of time, multiple commits from multiple features (represented by “F#” in the following diagram).

The Problems With The Status Quo

As time went by, we started working differently. Rather than having an unknown number of features in development, at any given point in time, we started refocusing our efforts to develop in vertical feature slices. There were a large number of advantages to this, including the ability to test one feature at a time and call it good. As our team size grew from more than one or two people, though, we found that we were again working on more than one feature at a time. This made sense in that we had multiple “feature teams” working on one feature each. But we started having problems… or at least, we started to recognize the problems that had always been inherent in our processes.

CI Builds Broken

In moving forward with multiple feature teams and everyone committing to the trunk, we started having problems with our continuous integration process. One team’s commits would cause another team’s work to fail the build… it wouldn’t compile correctly, or unit tests would fail, or … whatever the case was. We ignored our CI builds most of the time, and rationalized it to our project management team. The CI builds were essentially useless to us, at this point. I even remember hearing about a team that I wasn’t working with, turning off their CI build because “it’s always broken.”

We continued on, though, assuming that this was just the way the world worked.

Developer Downtime

We also started having problems on individual developer’s machines. A commit from one person would cause another person’s local changes to break, and they wouldn’t be able to continue working until the issue was resolved. There were times when this would take hours, if not days. This often led developers down the path of “I’m not going to commit until it works completely”. Since most of our development efforts would take days on end, if not weeks, we ended up in situations where developers would only commit once or twice a week. The possibilities of lost work, and the realized problems of people going on vacation or being out sick, caused a significant amount of problems. We set standards to commit often, and tried to enforce it, but continued to run into problems that caused the team members to not commit regularly.

So, we just continued working this way, under the assumption that this is how the world works.

Troubles With Testing

The other major problem that we had, was testing. We were trying to deliver builds to our business analysts and testers, as often as possible. We wanted them to give us feedback on how the system was working, whether the workflow was good, etc. The problem was that we had multiple features in the delivery, whether or not those features were ready for delivery. This left half finished code in place, and often left those portions of the system unstable or unusable. There were times when a core bottleneck in the software’s process would be broken – such as the login screen – and prevent the BAs and testers from doing any work to verify any part of the system that had changed.

We eventually started delivering “don’t touch this” lists with our builds. These lists were often rather lengthy, and contained nothing more than instructions on what the BAs and testers were and were not supposed to be testing at the moment. In spite of these lists, the testing process often required touching those areas, or the people testing would simply ignore the list. This lead to many issues tickets being opened against the system, for areas that we already knew were broken or incomplete. There was a lot of frustration between the developers who knew what not to touch, and the people doing the test, who thought they should be able to use the entire system at any given time.

Once again, we continued to work this way, assuming that there was nothing we could do about it.

Branching For Breaking Changes

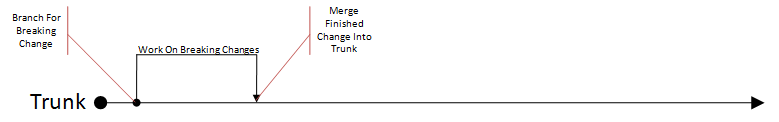

After struggling through these issues for a while, we started looking at the branching capabilities in subversion. I was wary of this at first, having had horrible experiences with it in visual source safe. After some trial and error, reading, and more trails, we finally figured out how to correctly branch and merge in subversion.

At that time, we decided that when we knew were going to have breaking changes, we would make those changes on a branch. This would allow everyone to continue working on the trunk, while the breaking changes were finished up on the branch. Once those changes were made, we would merge the changes back into the trunk and everyone would continue forward on the trunk, doing their small, regular commits for their work.

The Epiphany

Then, in October of 2008, I attended the Continuous Improvement in Software Development Conference (a.k.a. “Kaizen Conference”) in Austin. Most of the sessions that I attended centered around the principles of pull based systems. During one of the sessions, Dave Laribee talked about the idea of release per feature. I was hooked almost immediately as I suddenly saw “that’s the way the world works” as serious problem in how we worked with source control. Later on in the conference, Dave set up an open discussion to cover some of the issues and options that were surrounding the notions of release per feature. This was a tremendously valuable conversation for me, and I took a lot away from it.

By the end of the conference, I was excited about the possibilities of being able to code against my feature without having to worry about another developer’s feature bleeding into my change set and causing the problems mentioned above. After some discussion with my team, we decided to move forward with the notion of release per feature. There were a lot of other nuances that we included, which led us to a more complete Kanban system. In the end, though, I found that it did not matter what type of release scheduling we were doing. Whether we were working in a “waterfall” manner, a Scrum sprint, XP iteration, Kanban or other iterationless release per feature style, the notion of working in my own branch as the primary means of committing to source control stuck with me.

The Standards For Committing

At this point, I have a few standards that I set within every team I am working directly with. Many of these standards have been in place in my teams for a very long time – even during the problem years, mentioned above. The real difference is that we now have the ability to actually follow these standards without a great deal of administrative nightmare, like we previously had. The reason for this is standard #3 – Branch-Per-Feature.

- Commit often

- It doesn’t matter how small the change; if it compiles, you are allowed to commit

- Commit at least once, at the end of the day. You should never have uncommitted code on your machine, when you leave for the day

- Minimize CI Build Downtime

- Don’t commit broken unit tests or other test automation, to the CI build code base

- Our unit tests and integration tests should always be green on the CI server

- A broken CI build is a red flag that must immediately be rectified

- Branch-Per-Feature

- No work-in-process (WIP) is committed directly to the trunk

- Every feature team, task team, or bug fix, is worked on it’s own branch in source control

- Only finished work it merged into the trunk

Branch-Per-Feature By Name

The truth about “Branch-Per-Feature” is that it is only “Feature” in name. I make no distinction between a feature, a story, a bug fix, a task, or however else you want to segment the work to be done. The reason that I call it “Feature” is that we will group the work to be done, based on where the work is happening, functionally. That is, we group the work by the feature that it is tied to. But we do not limit the feature to a single branch.

If a given feature has 10 user stories against it, and we need more than one sprint or iteration to complete the feature, we will effectively create multiple branches for the same feature – one at a time. During the first sprint or iteration, the team that is working on that feature will work on the same branch. When the sprint or iteration is done, we will deliver the working version of that branch by merging it into the trunk. At that point, we either continue working on the feature branch, or we re-branch to simplify later merges. I prefer re-branching, honestly. It simplifies the trunk-to-branch-to-trunk synchronization during development efforts, by giving a clear cut start and stop in the revision history.

When a bug is found in the system, we will also branch for that bug. This follows the same grouping rules and heuristics as the feature branches, though. If multiple bugs are found against the same feature, we will include as many of those bugs as we can in the same branch and delivery set.

Except…

The major exception to Branch-Per-Feature, is the smallest of changes that has no impact outside of the change that you just made. A label might be misspelled, as an example. It would probably take more time and effort to branch for this, than it would be worth. However, if there is documentation that needs to be updated, screen shots that need to change, help files that need correcting, or … The full impact of that one label change needs to be understood before anyone decides to make that change directly on the trunk.

Therefore, the default rule of thumb is that everything is done on a branch. If anyone is ever in doubt, the doubter must discuss this with the team or team leadership and make their case for changing directly in the trunk. This does not need to be a bureaucratic process, though. It can be as simple as sending an IM, or walking to someone’s desk to say “hey, I don’t think I need to branch for …, what do you think?”

The Underlying Principles

There are some underlying principles or philosophies on why Branch-Per-Feature works so well: Decoupling and/or Sand-Boxing.

Decoupling

As a software development principle, decoupling says that we want to be able to change one part of the code without affecting the other. We also want to be able to replace or reuse one part of the code without having to bring along or change the others. When we start talking about Model-View-Controller, Composite Applications, Service Oriented Architecture, Message Bus / Enterprise Service Bus and other architectural concepts, we are still talking about the principle of decoupling. At this point, though, we are taking decoupling out of the class and method level, up into the architecture. So, why shouldn’t this principle apply to higher level organization and process, as well? I say we should be decoupling our feature set development efforts from each other. Don’t let one feature development effort require another feature development effort to coincide, change, or be inadvertently affected.

When we start operating our higher level processes like this, the undeniable truth of structure causing behavior begins to emerge. The system architectures and the lower level implementations also begin to reflect this idea. Composite applications suddenly become “well, duh. of course we do that”, as they facilitate the easy decoupling of the feature sets from each other. Furthermore, concepts such as Domain Driven Design’s Bounded Context are suddenly very real in our system (thanks, Udi!). Our structure and how we operate at a process level, begin to drive the behavior and values of the product that is being created in that structure.

Sand-Boxing

The idea of sand-boxing our development efforts is almost as ubiquitous as decoupling. The real difference is that most of us haven’t yet recognized the implicit sand-boxing that we do every day.

When was the last time you worked on a web project? Did you have every developer hitting a shared web server, when working on the functionality? I certainly hope not (and if you did, you have other issues that need to be addressed before you try branch-per-feature). Or, when was the last time you worked on a WinForms application? Did you have every developer using the same workstation computer to write their code? I doubt it, and again I certainly hope not.

Instead of forcing everyone into these types of irresponsible bottlenecks and resource limitations, we provide developers with workstations that can run the Web app or the WinForms app directly on their machine. This is sand-boxing. This is letting everyone have their own little world in which they can control the variables and limit the interactions, changes, and other forces that want to impede their progress. So why wouldn’t we want to continue that sand-boxing mentality outside of our individual workstations? We should be providing a complete sand-box for the individual or team effort, as needed. A developer or team of developers should be in control of the resources they need to get their job done. This includes not only the workstation and web site or winform host, but also the source control, database, messaging bus, and other resources that are needed for the effort.

To illustrate how far this can (and possibly, should) be taken, I am currently working with another team lead to define a VMWare Workstation image that his entire project development stack is installed into. This will give everyone on the team a complete sandbox, wrapped up neatly into a VM that can be updated and redistributed easily. The only part that will not be sand-boxed into this VM, is the source control… but we will still sand-box the source control via branch-per-feature.

The Cost Of Branching And Merging

A few of the comments that I’ve seen, recently, indicate that people are wary of the administrative overhead for this. I’ve even heard indication that some people don’t want to dedicate an individual person to be the ‘branch admin’ or ‘subversion admin’, to handle the branch and merge needs. I don’t think this is the right idea at all. On my team(s), every individual has been properly trained on how to branch and merge in our source control system. This goes for the most senior of developers, as well as the college interns that are on my current team. The training of how to correctly branch and merge takes no more than 30 minutes for the whole team, and then a few follow up sessions with individuals as they try to do it for the first time on their own. The net result, though, is that I don’t have to worry about it anymore. I don’t need a ‘branch admin’ or anyone else that has ‘uber-svn skillz’, because subversion makes the branch and merge process fairly straightforward and simple (and if you’re lucky enough to use Git or another distributed system, you don’t even need to worry about this because branch-per-team/feature is the natural workflow).

In subversion, creating a branch is a “constant-time” function. That is, it does not take any more time to branch one file with no history, than to branch 300 gigs with 30,000,000 commit history. Merging, on the other hand, takes some time and patience to learn. However, the ability for a large scale team to work in smaller, independent feature teams has made a tremendous improvement in productivity for us. The shear reduction in communication overhead to coordinate 10 or 15 people all committing the trunk multiple times a day, is in itself, paying for the additional overhead of branching and merging.

The Benefits

Having worked in a Branch-Per-Feature mode for almost a year now, I am all but refusing to work in any other way. I no longer have to worry about other developers clobbering my WIP. I no longer have to worry about clobbering their WIP. I can deliver my build to the BA or Test environment, without fear of someone else’s feature being half-done and getting invalid tickets entered against my feature. I can even do a complete release to production based on a single feature being complete, at this point. In fact, my current customer prefers to have single features released and even wants to pay us by completed feature.

The end result is that we can have multiple feature teams working on different features, without clobbering each other. The cost of branch management is negligible compared to the benefits of decoupling our feature development. The ability to process multiple features in parallel, is essentially like working on a single feature; with the added benefit of working on multiple features. Now, there does come a point where the features merge into each other. The strategy for merging is very context dependent, though, and will be covered in future posts in this series.

Coming Up, Next

In the next part of the Branch Per Feature series, I’ll cover the high level How-To. This will give the overview of the steps that need to be taken, all from the perspective that it should not matter which source control system you are using. A future post will then cover the specifics of how I manage Branch Per Feature in Subversion, and another will focus on CI-Build-Per-Branch. I’ll also try to include a “lessons learned” post, at some point. We made a lot of mistakes in the process of learning how to manage branch-per-feature, and I’m hoping that I can help others avoid them.