Branch-Per-Feature Source Control. Part 2: How (Theory)

In the first part of my Branch-Per-Feature (BPF) series, I talked about why you would want to use a source control strategy like BPF – what circumstances would warrant such a strategy, what problems it solves, and a little bit of the cost involved.

I had originally intended to combine the strategy and theory of how to do Branch-Per-Feature into a single post, for my second entry. However, after fleshing out most of the How (Theory) and half of the What and When (Strategy) sections, I decided that the information represented by these two concepts was distinct enough, and large enough, to warrant separate articles. So, this time around, I’m going to walk through the high level, somewhat source control agnostic theory on how to do branch per feature.

For the remainder of this article, I am going to use the word “feature” to represent any work that warrants it’s own branch. This will include features, user stories, bugs, or any other breakdown of work that you may use. The point is not to say that other breakdowns are not correct or valid, but to simplify the language and explanations throughout the explanations.

The next post will cover the strategy of when to branch and merge what.

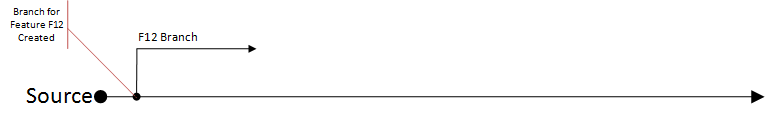

Branching Your Feature

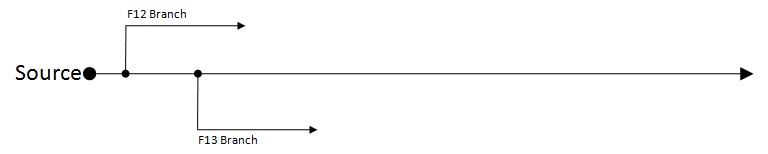

Creating the branch is the most basic part of the Branch-Per-Feature process. At the point in time that work starts, you create a branch from your main line of development – typically, the trunk or master (which I will call “source”, for the remainder of the article). For example, if we are starting on Feature #12 (F12) right now, we would create a branch for it. The team working on F12 will do all of the work for it on this branch.

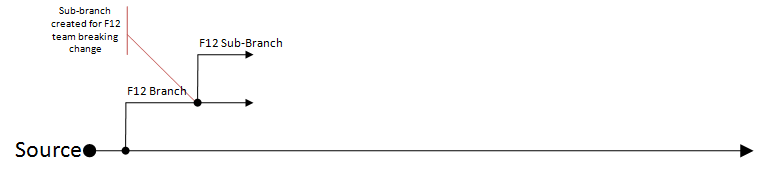

Sub-Branching Tasks

If a feature team is made up of several persons, you may end up in a situation where you want to break the feature down into individual tasks that each person can work on. This division can be done in a number of different ways with both vertical and horizontal segmentation. You may have all of the team members working on the branch directly, but you may also have some situations where a feature team member has to introduce breaking changes. In these cases, you need to consider how long the breaking change will take and when the other team members will be able to use the changes made. If the breaking change in question is going to take more than a few hours, or if the team member(s) working on the breaking change want to commit often and not worry about clobbering other developers, then we need to consider a sub-branch for their work.

Branching for breaking changes is one of the most common scenarios for branching, that I’ve seen in source control usage. We should apply the same logic and principles to sub-branching, when doing Branch-Per-Feature, and allow our team members to use this technique to further help segment the development effort.

We do have to be careful in how far down this path we go, though. If we start creating sub-sub-sub-sub branches, we can easily run into an administrative nightmare and forget which branches are from where and when. If we try to limit our sub-branches down to breaking changes for a feature branch, though, we should be able manage them fairly easily. Each feature team members knows which feature they are working on, so they should know which branch they came from and need to merge back into.

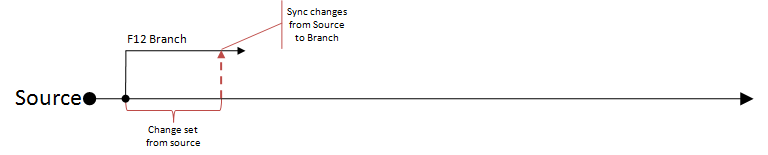

The Merge Dance: A Single Branch

Whether you are merging a feature branch into the source, or a sub-branch into a feature branch, the process is the same. Furthermore, this is the standard process for merging any branch, whether you are using a branch per feature strategy or not.

If you have ever done the Check-In Dance, the overall process of merging a branch – the Merge Dance – should be a familiar one.

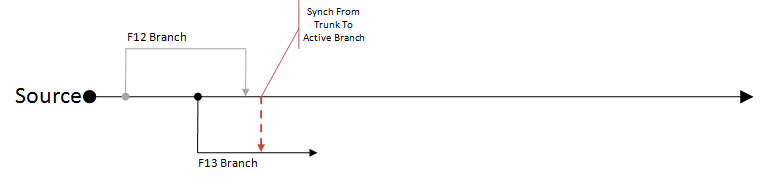

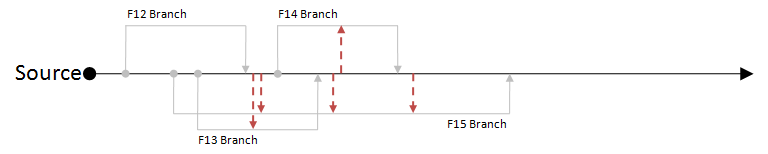

1. Synchronize From The Source

The first step to take is to bring all of the changes that have occurred on the source, up into your branch. This includes resolving any merge conflicts that you may encounter during this process.

</p>

</p>

The synchronization process, including the conflict resolution, is the responsibility of the team that is working on the branch. They need to ensure that all of the changes from the source are correctly applied to the code that they are working on. This may involve some discussion with the people that made the changes on the source, if there are conflicts or extenuating changes that need to be examined.

2. Smoke Test The Branch

Once the source changes have been synchronized into the active branch, the team working on the branch is then responsible for running a smoke test. If you have a unit test or other automated test suite, it would be a good idea to run all of those test suites against the branch. If your automation suite takes hours to run, you want to have a ‘smoke test’ or ‘fast’ suite of tests that can be executed in lieu of the entire suite.

The specific test suite you run is context dependent, of course. You need to look at the changes that are being brought in, to determine the best course of action. Your team’s overall testing strategy becomes a vital part of your branching and merging strategy, at this point. Understanding how to achieve ‘just enough’ testing for the sync into your branch will likely come with experience, through trial and error.

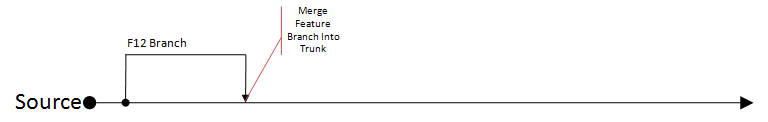

3. Merge Into The Source

After you have smoke tested the branch with the changes form the source, you’re ready to merge into the source. There’s nothing terribly special about this step. It’s just a merge process from your branch into your source. Since, at this point, you have all of the changes from the source in your branch, you should get a merge change set that reflects the real work done in your branch.

</p>

</p>

4. Test The Source

Once again, the suite of tests that you execute is context dependent. If you are merging a sub-branch into a feature branch, you may only need to run the smoke tests on the feature branch. However, if you are merging into the source, you will likely want to run your entire test suite against the system. Hopefully you have a Continuous Integration server set up that can execute these tests for you. Whether or not you do, though, there is no substitute for the human factor in testing. I highly recommend that you do at least a modicum of exploratory testing for the areas of the system that were modified in the branch. For a small branch, this may only take a minute or two. For a larger feature branch, though, this may necessitate a much more involved and rigorous test plan.

Merging With Multiple Active Branches

Merging a single branch into the source is easy enough. Anyone that has ever worked on a breaking changes branch should be familiar with this process. If you were not familiar with this process, though, I hope that the preceding section has filled in the missing detail for you. A far more interesting challenge, though, is merging with multiple active branches and keeping them synchronized at the right points in time.

Two Active Branches

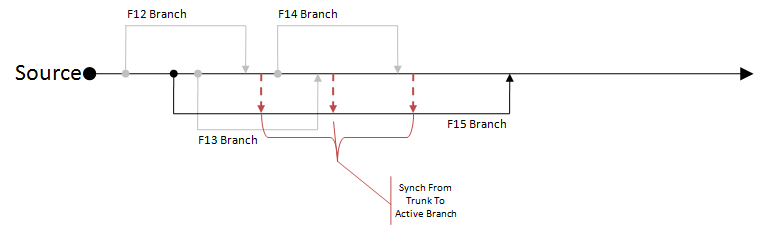

If we have Feature #12 (F12) in progress and Feature #13 (F13) begins at a later point in time, we will have a source tree similar to this:

If the team for F12 is ready to merge before F13 is done, they will follow the standard Merge Dance as outlined above. Once F12 has been merged into the source, it is now their responsibility to inform the collective team of the changes to the source. The F13 team would then be responsible for synchronizing from the source into their branch, and they would follow step 1 and step 2 of the Merge Dance.

Why should F13 synchronize once F12 has merged into the source? Because we expect all future work to contain the feature set and functionality from the F12 branch. We would not want the F13 team to merge into the source at a later point in time and blow away the changes made by the F12 team. Additionally, there is a very real possibility that F12 will be affected by the changes being made by F13, or vice-versa.

The F13 team should synchronize from the source as soon as possible. This will help the F13 team stay on top of the integration between F12 and F13, ensuring that they don’t continue forward with changes that will break between the two features. Once synchronized, F13 would continue working on their branch until they have completed their feature. They can then merge their changes into the source with far more confidence that they are not breaking the system.

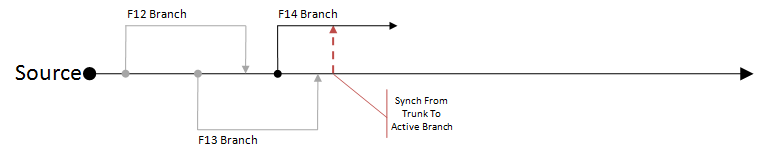

More Active Branches

Now lets say that Feature #14 (F14) begins after F12 has merged into the source. F13 then merges into the source after F14 is created. To ensure F14 is up to date with all of the latest features and functionality, the same process that I just outlined is followed. After F13 merges into the source, F14 will need to synchronize. This cycle can repeat itself indefinitely, with as many features as you can imagine.

A previous team that I was on, was able to continue this process for more than 4 months with no significant issues. In fact, once we got into the groove and really got good at the Merge Dance, it became second nature to the team. Every team member, including the junior developers, were able to do the Merge Dance practically in their sleep.

Long Life Branches

Of course, we don’t always have such a simple cycle. We often work in larger project teams with many smaller feature teams. We sometimes have branches and features that run into trouble or need more work than originally thought. We have small bug fix batches that get branched and merged more frequently, and we generally end up in situations where a single branch will outlive many other branches. In this scenario, the same principles and process still apply. When a branch is created, it is the responsibility of that branch’s team to keep it up to date with the source.

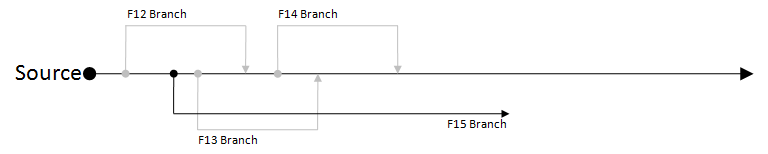

For example, let’s say Feature #15 (F15) was started shortly after F12. F15 turns into a very long running branch for whatever reason, and continues to live on even after F14 is done.

Every time another feature is merged into the source, the F15 team is responsible for synchronizing those changes to their branch. There will be three points at which the F15 team needs to synchronize: after F12 merges, after F13 merges, and after F14 merges.

In spite of the long running nature of this branch, the process is the same. It only introduces more points at which the F15 team needs to synchronize from the source.

A Complete Picture

The number of active branches that we had in our repository directly dictates the number of merges into the source. With a total of 4 branches, we can see 4 distinct merges. Over the life of those branches, though, we have to account for the number of synchronizations from the source out to the active branches. From this perspective we end up with 5 points in time that we we needed to synchronize to from the source.

If it takes an average of 1 hour to perform the Merge Dance (and I hope it doesn’t. That’s a very high estimate, by my own experience), and an average of 30 minutes to synchronize from the source (since the sync process is 2 out of 4 Merge Dance steps), then we have spent a total of 6 1/2 hours managing our branches. If these 4 branches took 1 month (20 business days) total, to complete, then we have spent just over 4% of our time managing the branches.

The advantage that we have gained, with this 4% overhead, though, will hopefully outweigh the cost. I’ve worked on teams where we would spend far more than 1 day a month fighting the broken builds and bad deliveries. In the end, I have seen the cost of Branch-Per-Feature as a reduction in the overall cost of developing new features. (For more discussion on the cost, benefits, and why of Branch-Per-Feature, check out the first article in the series.)

Coming Up Next

I’m hoping that I’ve given a more complete picture of Branch-Per-Feature, at this point. It is by no means a silver bullet, and there will be times when it just doesn’t make sense to add the administrative tasks of branching and merging to a small fix or change. However, the general process is fairly straightforward once you have practiced the Merge Dance a few times.

If you are using a sensible source control system, such as Subversion or Git, then there should not be a need for a ‘source control admin’ position on your team, either. I’ve trained even the most junior of developers – interns from a local college – on branching and merging, with great success. It is not rocket science or black magic. It only requires that you follow the steps that are appropriate for your task at hand.

A future entry in the Branch-Per-Feature series will cover all of the steps of the Merge Dance and the overall process of managing branches, with Subversion specifically. The next entry, though, will be some additional theory and strategy for handling Branch-Per-Feature. I will try to outline the basic pieces of information that you need, to create a branching and merging strategy (what and when) for your specific situations, by giving examples of circumstances in which I have used BPF.