Are We Continuously Improving Or Just Continuously Changing?

Don’t confuse activity – even when it has a visible, measurable effect – with productivity. Without a clear picture of where we are going and why, our best efforts at improvement (though they may be ‘continuous’ efforts) are likely to be change for the sake of change. At best, change without direction has a chance of doing something useful and making part of our system easier to work, reducing cost relatively soon. At worst, change without direction has is a direct cause of lost revenue as we are spending our time and money to change areas of the system that are not causing any immediate financial difficulties. Worse yet, even when we have a goal set, we can still do financial damage to the project and company.

Flailing About, Believing We Are Improving

At a previous job, I was working on a product with a team that had been together for a few years. We had a rapidly evolving set of standards and were making constant technical improvements to the architecture and infrastructure of the application. At one point, we needed to add some functionality to a part of the application that was used by two processes. The architecture and code for that part of the app was ‘old’ by our standards and we needed to update it to support the new functionality. After discussing what needed to be done with the management / technical leadership of the team, we sent a developer down the path of rewriting the screens and process involved in this part of  the app.

the app.

6 weeks later, we had a rewrite of the functionality that gave us nothing in terms of adding the new functionality. We had flailed about with our eyes closed, frantically rearranging puzzle pieces, cutting them apart and gluing them back together in a manner that let us use them easier. Yes, the code was easier to read and understand. Yes, the code was well tested (done entirely with test-first development). But the goal of being able to add the new functionality, easily, was missed entirely. We were effectively sitting at ground zero, staring at the same implementation problems that we started with from the perspective of the needed functionality.

After some digging we realized that the problem was directly the fault of our management efforts, relating to goals and direction. We gave the developer the task of re-writing the functionality but we never set any goals for how the rewrite should be done, to support the new functionality that we needed. In the end, we realized that we had wasted thousands of dollars and hundreds of man hours because we didn’t have the right goal set for the change we were engaging in.

What Technical Debt _Can_ We Pay Down?

My current team is working on a product that is now 7+ years old. It has a lot of “legacy” code in it, to say the least. The amount of technical debt that we encounter on a daily basis is staggering. But that’s too be expected on a product of this size and complexity, with a continuously evolving landscape of ‘best practices’ in the .NET arena. The good news is we have a continuous effort to improve the system instilled in the team – and it’s been there for at least the last few years (I don’t know the entire history or timeline because I’ve only been here for a few months). However, there are still some very dark, disturbing creatures that like to raise their heads out of the depths now and then, demanding the sacrifice of one’s soul in order to get the current task done. But, all snarky commentary aside, we manage to change the system a little more every day and we are slowly moving forward to a … well… toward what? A system with less technical debt, I suppose. But for what purpose? To allow what to happen?

And now add Dave Laribee’s first article on Technical Debt in MSDN Magazine into the equation. My team – management included – is now gung-ho about paying down technical debt, after reading this. There’s plenty of reason to be gung-ho about it, too. The article paints a very telling picture of technical debt and why it’s bad. There’s a lot of good info in there and I highly recommend reading it. However, I believe Laribee got it wrong when it comes to choosing what technical debt to tackle, by introducing the use of Luke Hohmann’s “Buy A Feature” Innovation Game.

And now add Dave Laribee’s first article on Technical Debt in MSDN Magazine into the equation. My team – management included – is now gung-ho about paying down technical debt, after reading this. There’s plenty of reason to be gung-ho about it, too. The article paints a very telling picture of technical debt and why it’s bad. There’s a lot of good info in there and I highly recommend reading it. However, I believe Laribee got it wrong when it comes to choosing what technical debt to tackle, by introducing the use of Luke Hohmann’s “Buy A Feature” Innovation Game.

In the article, there is an example of the New York City streets vs. the Atlanta, Georgia streets. It is a very compelling and a good example of long term, goal oriented thinking. We can make some sweeping assumptions about how New York seems to have had a goal of creating a systematic, simple to navigate street layout and naming / numbering convention. They likely wanted people to get to and from their destinations with relative easy. With Atlanta, though, it seems that the goal was to use the existing “cattle paths” as the road layout – to simply grow a new infrastructure of roads on top of an existing, outdated system of paths. There’s a wealth of metaphor that can be drawn from this, but the example is misleading in the context of the article.

Shortly after the street layout example, the article suggests the use of the Buy A Feature game to determine what debt to pay down. The problem is not the game itself – there are plenty of circumstances where this game is appropriate – but that it is being used in a circumstance where it does not serve it’s purpose. This game is essentially a more interesting variation on a standard voting system for what to do next. My team has basically been doing for the last week or so – but using a vote count instead of a dollar amount. We’ve gathered together a list of problem areas, prioritized that list a little, and set about voting on the items in the list. The problem with this approach – whether we call it Buy A Feature or not – is that it inherently pits the team against each other and facilitates a flailing about in terms of what should be worked on. In some cases, we end up with various team members that are very persuasive, taking control over the conversations and convincing other less persuasive team members that they need to vote a certain way. In other cases, we have developers voting independently of each other, with no rhyme or reason in terms of the big picture, creating a scattershot of “I had to touch this part recently so I want to fix it” throughout the system.

for what to do next. My team has basically been doing for the last week or so – but using a vote count instead of a dollar amount. We’ve gathered together a list of problem areas, prioritized that list a little, and set about voting on the items in the list. The problem with this approach – whether we call it Buy A Feature or not – is that it inherently pits the team against each other and facilitates a flailing about in terms of what should be worked on. In some cases, we end up with various team members that are very persuasive, taking control over the conversations and convincing other less persuasive team members that they need to vote a certain way. In other cases, we have developers voting independently of each other, with no rhyme or reason in terms of the big picture, creating a scattershot of “I had to touch this part recently so I want to fix it” throughout the system.

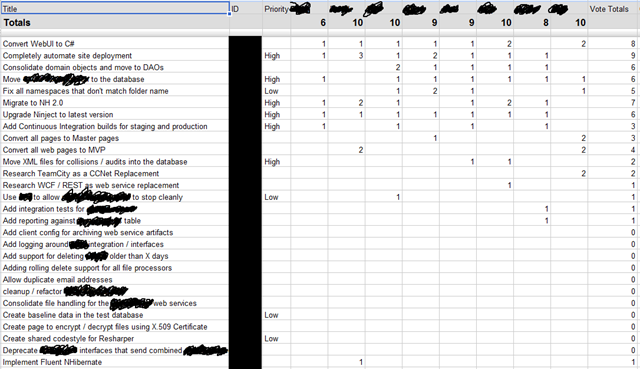

To illustrate the problem, take a look at the current voting from our technical debt list. (I’ve scrubbed the names of the voters and a few of the items)

Though there is a relatively close grouping (due to a sort that was done on Vote Totals just prior to all votes being cast), we can clearly see a scattershot effect taking place. There is not one item that is unanimously agreed upon and there are several items where only one or two people feel that it is important enough to warrant a vote. Even if the entire team (or the majority in the case of some of these items) agrees on what should be done, we still run the risk of flailing about in our improvement efforts… just because we want to do these things, doesn’t mean we should.

What Technical Debt Do We _Need_ To Pay Down?

From what I gather, the MSDN article assumes that the elimination of technical debt is the goal in itself. If that’s true then the Buy A Feature game may be an appropriate tactic for determining what should be worked on, next. However, I’m betting that your company doesn’t want to spend 6 weeks of effort re-arranging the puzzle pieces with your eyes closed, the way my previous team did. You, like everyone else in the software development business, have customers and managers and product owners and everyone else with a stake in the product wanting delivered functionality that people will pay for.

Mike Rother paints a very powerful picture of how to approach a situation with many different options, in his book Toyota Kata. He correctly points out that the problem with most improvement efforts is that we spend all of our time focusing on what we can change, instead of what we need to change. When I first read this, I had no clue what the real difference was – or at least I didn’t understand how you could know what needed to be done vs. what could be done. It was when he started talking about the long term vision and target conditions, that it all started to make sense. I had previously seem similar work in Patrick Lencioni’s book, Silos Politics and Turf Wars. In this book, Lencioni talks about how we can eliminate the organizational problems listed in the book’s title by creating a unifying vision of where we need to go. Lencioni calls this the “Thematic Goal”. Rother’s calls this a “Target Condition”. The purpose is to provide focus and direction for our efforts. They give us something to strive for, something to accomplish, and a way of knowing that we are making progress and enacting change with a purpose, not just changing for the sake of change.

and target conditions, that it all started to make sense. I had previously seem similar work in Patrick Lencioni’s book, Silos Politics and Turf Wars. In this book, Lencioni talks about how we can eliminate the organizational problems listed in the book’s title by creating a unifying vision of where we need to go. Lencioni calls this the “Thematic Goal”. Rother’s calls this a “Target Condition”. The purpose is to provide focus and direction for our efforts. They give us something to strive for, something to accomplish, and a way of knowing that we are making progress and enacting change with a purpose, not just changing for the sake of change.

The scope of a target condition (my personal favorite of the two names) is to specify a state at which we want to be, within a given time period, budget and other constraints that we may need to account for. Typically, we should look at something that is a few weeks to a few months out and does have a readily apparent solution. (If we already know the solution then we don’t need to plan, prioritize or question what should be done. We would skip right to implementing the solution.) By doing this we provide a focus that our efforts can be aligned to. With our efforts aligned, the question of what to work on next easily moves away from “what can we work on?”, to “what do we need to work on?”. We can use the target conditions to help eliminate the organizational problems of us vs. them, pursuasive vs. passive employees, and the other issues associated with voting mechanisms and directionless action.

There are additional benefits to working within target conditions, as well. For example, it is well known that people are motivated by accomplishment of goals that they see as challenges – especially when they help to define and implement the solutions for the challenge. When setting up a target condition, we should introduce a challenging goal… something that can’t be immediately solved. We need a stretch goal with issues that we need to work out from a technical, human and/or process perspective. If we setup a target condition like this and turn people loose on brainstorming the challenges and solutions, we end up with the full potential of human creativity and ingenuity being tapped. Job satisfaction comes quickly when the solutions people implement to the challenges that face them, are the ones they suggested.

Refocusing The Payment Of Technical Debt

The problem that our team faced in the effort to reduce technical debt is that we had no team focus – no unifying theme that will tell us what we need to work on, next. When faced with a technical debt problem, we assumed that “eliminate technical debt” was in itself, a valid goal. If we were in the business of writing clean code, then this may be valid. However, we’re in the business of providing features and functionality to our customers so that their jobs can be done faster and more accurately with less effort.

The good news is that we do have a target conditions – we just didn’t know it or didn’t realize that we needed something more specific than the elimination of technical debt. The following is from an email that our manager sent out, with a few of my own edits to clarify some points and remove some information.

Complicating our situation today is how we do testing. [edit: we are staggering sprints between development and testing] Where we want to be is that items get finished by the developer and then get tested as soon possible. This leaves ample time for developers to make needed fixes should there be bugs, and also leaves time at the end of the iteration for the PMs to do the final acceptance review. We have not been doing final acceptance review, and we want to change this.

_ _The way we operate today, we only update [our internal test environment] on Monday mornings (or ad-hoc during the week if there’s an update needed after a bug fix). So testing can’t begin until Monday, because the new code isn’t available. The dev team will start working on figuring out how to get completed code into a testable state more quickly so that testing can commence.

_ _However, I think we can say that it is in everyone’s best interest to get the testing done as soon as possible, and to not leave it until the end of the last week before a release.

_ _I would very much like to see us getting more testing done earlier, and I would really like to see us not leave the testing of both iterations/milestones until the second week. We can’t go easy on the week in which we don’t have a release. Doing so puts a lot of pressure on, well, everyone when it gets left so late.

Setting Up A Target Condition

This email provides a perfect opportunity to clearly define a target condition. Having a target condition then allows us to answer the question of what technical debt needs to be paid down, now.

Let’s define the target condition based on the information in the email.

The Target Condition

- Delivery of new functionality and bug fixes to the internal testing environment, immediately after development work is done

- Formal testing immediately after deployment to internal testing environment

- Project Manager / Product Owner “final acceptance review” prior to delivering functionality to production environment

Some Of The Work To Be Done

(Note that this is only an sample of some work that needs to be done to achieve the target condition)

- Deployment of completed features without bringing along incomplete features

- Full automation for deployment process

- Isolation of feature development

- Better integration of / communication between dev and test team

- Coordination between dev / test / PM for final review

- May need a better CI server to support deploying to many different environments, easier

Notice how many of the items from the current voting list of technical debt didn’t make it into this list. This is because not everything that we want to work on will have an immediate impact on us moving toward the target condition. There may be other target conditions that will be affected by items that dropped off the list, though. The technical debt items will make their way back into the list of what we need to work on, as our target conditions are met and new ones are specified. It’s also important to note that not everything in this list is “technical debt”. There are some process and human interaction issues that must be addressed, as well. The target conditions that we choose will determine what needs to be worked on – not the other way around.

Notice how many of the items from the current voting list of technical debt didn’t make it into this list. This is because not everything that we want to work on will have an immediate impact on us moving toward the target condition. There may be other target conditions that will be affected by items that dropped off the list, though. The technical debt items will make their way back into the list of what we need to work on, as our target conditions are met and new ones are specified. It’s also important to note that not everything in this list is “technical debt”. There are some process and human interaction issues that must be addressed, as well. The target conditions that we choose will determine what needs to be worked on – not the other way around.

Pulling Principles From The Illustrations

The focus of my illustrations has been technical debt, in this post. However, the principle that underlies the issue – using currently target conditions to drive our improvement efforts – is universal. The effort we put into change does not have to go to waste. We don’t have to end up wasting 6 weeks of effort, as in my first example. We can ensure improvement is happening, rather than guess or vote and hope we are not just changing, by setting target conditions for our teams and working toward those conditions, continuously.

Other Conditions For Paying Down Debt

Since the illustration in this post is technical debt, I wanted to address some concerns that I know will come up.

I want to point out that it doesn’t always take a target condition to set up the circumstances in which technical debt should be paid down. There are other conditions, such as a defect report, that can create the necessary circumstances. For example, when a team receives a defect report the surrounding code should be scrutinized and a determination of whether it is cost effective (from a long term perspective) to invoke the boyscout rule should be made.

There going to be times when a voting process is appropriate for managing technical debt, too. For example, if a team knows that a significant amount of cleanup must be done before the project can move forward with its current goals, then there may be a need to prioritize what is cleaned up, when. There may also be a need for management to allow the satisfaction of some technical itch in the development team. It may be beneficial to morale and personal pride in the work being done to allow a team to have some Buy A Feature money, giving them the opportunity to express their own interest in solving their own pain points. There may even be a target condition to improve morale or solve some architectural issues that would account for this…

The point is, we need to remember that context is king and your circumstances need to be evaluated for what they are.