Writing A Thor Application

I’ve talked about what I went through to learn thor, already. After all of that, I found myself becoming rather fond of thor and the end result of learning thor was a nice little command line tool that I am automating with a cron job.

More Than Just A Script

I would call the typical thor script example and usage nothing more than a script. They are typically very small, very simple and single purposed – even when used as a rails generator. In my case, though, I am writing what I would consider to be a full-fledged application. I need some business logic and process, some data access, and a command line tool that supports a variety of parameters and options. Thor was a natural design choice for me because I love working in ruby and thor makes command line tools dirt simple, once you’ve learned the basic syntax.

As my app began to accumulate features and command line options, such as the ability to turn on verbose logging, I found myself wanting more than just a single file with all of my application’s code stuffed directly into the thor class. There aren’t any real ‘best practices’ or guidelines or anything in the thor documentation for how to go about doing this. Since a thor script is nothing more than ruby code, though, it is a fairly simple thing to use existing ruby idioms for organizing your files.

I decided to borrow a few ideas from rails and rubygems, and this is what I came up with.

A Basic File And Folder Structure

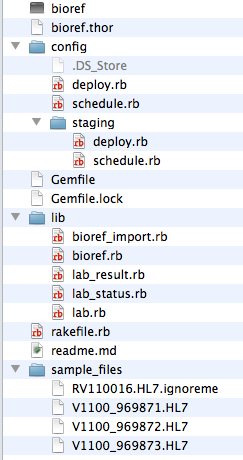

I decided to use a few rails and gem folder conventions to organize my code. Specifically, I needed to support multiple environments for my deployment – test, staging, production, etc. To do this, I went with the rails convention of a config folder with sub folders for each environment. Rather than having rails conventions for other folders, though – such as models and controllers, which I don’t need to separate so much – I decided to go with the lib folder convention of rubygems. This folder will contain all of my models and business logic for the application. At the root of my app’s folder structure, I put my rakefile, Gemfile, readme, the actual thor script and an executable to run everything. I originally had a bin folder to contain the thor script and the executable, but decided that this was not needed since I was not packing and deploying as a gem. Instead, I’m using Vlad The Deployer in a manner similar to a rails app – but that’s another blog post on it’s own.

Here’s the basic file and folder structure that I ended up with. Note that I only have a “staging” folder in my config environments at the moment. This is because the staging environment is the only one that has this app deployed to it, at the moment. I’ll create the other environment config folders as I need them.

The Thor File, The Executable Script, And DRYing Up The App

Every sample thor file I’ve seen has all of the thore code written directly in the .thor file, allowing thor to read the file and see the class that it needs to parse. In my case, I still wanted the thor file around so I could have something easier to test with, install it as a global thor script, etc. However, I wanted to have the end result as an executable script file. This meant that coding everything in the thor file directly or in the executable file directly, would creating more duplication than I was willing to live with. Fortunately, a thor script is just a ruby file. This means I can split my actual thor class into it’s own .rb file and require it into the thor script and the executable script.

The contents of my .thor file end up being this:

$: << File.expand_path("../lib/", __FILE__)

require 'bioref'

Yeah… that’s it. I’m setting up the ruby $LOAD_PATH to search my lib folder so I can easily load all the files I need, and then I’m requiring the bioref.rb file out of that folder. My ./bioref executable script only has a few additionals line when compared with the .thor file:

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

$: << File.expand_path("../lib/", __FILE__)

require 'thor'

require 'bioref'

Bioref.start

The difference here is due to the way thor works from the command line. When I run thor and it reads my .thor file, it has already loaded itself into memory, therefore I don’t need to do a require ‘thor’ in the .thor file, itself. However, when running as an executable script, thor is not automatically loaded, so I needed to include the require ‘thor’ in the executable file. I also have to call Bioref.start – the start method on my thor class – to run the actual thor class. Still, this is a pretty simple script to execute.

In the end, there is only a few lines of duplication between these two files – the load path and the require statement. Other than that, my entire thor application is all DRY’d up, minimizing the changes that I have to duplicate anywhere in in the app.

Bioref.rb: My Thor Class And App Bootstrapper

Each of my command line script does a require ‘bioref’ to load up the bioref.rb file from the ./lib folder. This file contains the actual thor class, with all of the command line options. This file also boot-straps the rest of the application by requiring all of the other files that I need and kicking everything off. I did my best to keep this code as small as possible, as well. I did not want any business logic in here. I wanted to keep it to the bare minimum of what thor provides and call out to my models for the real application processing.

require 'mongoid'

require 'ruby-hl7'

require 'ostruct'

require 'bioref_import'

require 'lab_result'

require 'lab'

require 'lab_result'

require 'lab_status'

class Bioref < Thor

desc "import FOLDER", "Import .HL7 files from the specified folder"

method_option :keep, :aliases => "-k", :type => :boolean, :default => "false", :desc => "true = keep the files that were imported. false = delete the files after import"

method_option :database, :aliases => "-d", :default => "app_development", :desc => "Mongo database name"

method_option :server, :aliases => "-s", :default => "localhost", :desc => "Mongo database server name"

method_option :port, :aliases => "-P", :type => :numeric, :default => nil, :desc => "Mongo database server port #"

method_option :user, :aliases => "-u", :default => nil, :desc => "Mongo database user name to authenticate with"

method_option :password, :aliases => "-p", :default => nil, :desc => "Mongo database password to authenticate with"

method_option :patient_id, :aliases => "-i", :default => nil, :desc => "Force the files to import for the specified patient id"

method_option :accession_number, :aliases => "-a", :default => nil, :desc => "Force the accession number used to match the lab order, otherwise accession number is read from the HL7 file"

method_option :verbose, :aliases => "-v", :default => nil, :desc => "Outputs a ton of logger data to STDOUT"

def import(folder)

server_options = OpenStruct.new(options)

importer = BiorefImporter.new(server_options)

importer.import(folder, options)

end

end

Yes, this file is fairly large. Notice what the majority of the file is, though: require statements and thor’s method_options. The actual executable code consists of three line of code. One to convert the hash of options into an openstruct (and it’s debatable as to whether this even adds any value… probably doesn’t, honestly), one line to instantiate my app’s primary class to run the import process, and one to actually run the import process.

From There, An App As Any Other App

At this point, the files that live in my ./lib folder represent the models and business logic that I need for my application to do it’s job. I’ve separated the command line and boot strapping process out of the models, and kept things fairly clean in that respect. This let me focus on what my models actually need to do from a business process perspective, ignoring the syntax and technologies of getting the app to actually run from the command line. I was able to write my models as if I were working in a rails app or working on a gem, and things just work. It’s quite nice, really.

You may have noticed the first line of require statements in my bioref.rb file, as well. Yes, I am using mongo db and the mongoid document mapper in a non-rails app. You’ll also notice that a good number of the options for my thor script are related to configuring the database that the app uses. It turns out that mongoid is really easy to use outside of a rails app. But, that’s another blog post on it’s own.