Git Branches: A Pointer, With History And Metadata

A few months ago, I had an “AHA!” moment working with git. I was doing one of my usual fixes for a mistake I had made and I had the realization that a named branch in git can be thought of as a pointer in C or C++ programming. I’d heard a number of people say similar things in the past, so it certainly wasn’t an original thought. However, it was an important realization for me and it has begun to influence the way I think about and work with git, and the way I approach teaching git.

Pointers: A Location In Memory

Software systems run in memory, and memory can be accessed through various mechanisms including named variables. Sometimes we don’t want to access the memory as a data structure or object, though. Sometimes we want to access the location of the memory where the data structure or object exists. To do this, we use a pointer. A pointer is a named location in memory – a variable who’s contents are an address in memory. A pointer can also be moved around, too; it can change what it is pointing to.

Of course, this is an over simplification of pointers, purposely. There’s a lot of nuances to pointers that I don’t understand anymore (it’s been 15+ years since I’ve dealt with them). But the oversimplification gives us a starting point to work with for a perspective on git commits and branches.

Branches: Named Pointers

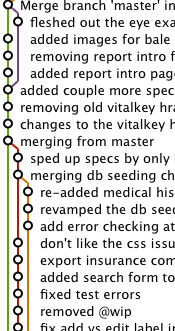

Take a look at a typical timeline in a git repository, using GitK or GitX:

There’s nothing special or unusual here… just a series of commits on a few branches, eventually being merged together. I typically describe this layout as a mass-transit system. Each circle in a mass-transit system is a stop along a route. Each route is defined by colored lines. You can see routes diverging and coming back together – branches being created and being merged – flowing form oldest at the bottom to newest at the top. This perspective helps us understand the history of a git repository. We can see the timeline of commits, the divergence and convergence of branches, and how everything is related to everything else.

There are several branches in this screen shot – but none of them are named. Git knows that these branches exist because of the metadata associated with the various commits, creating divergence in two or more directions from a single commit. These are implicit branches in git and are not addressable as a “branch” in the conventional sense.

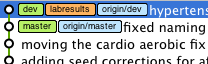

If you want an explicit branch in git, you need to have a named HEAD (or pointer) that points to the commit you want to address.

Each of the five labels in this screen shot is an explicit branch – a named pointer that is addressable as a “branch” in git, and points to a specific commit. Notice, though, that there are only two commits in this screen shot in spite of 5 named branches being shown. If you think of each of these named branches as a pointer variable, it starts to become a little more clear. We have 5 pointers. 3 of them point to the commit highlighted in the blue line and 2 of them point to a commit just below that one.

Pointers Are Easy To Manipulate

In C/C++, pointers are easy to manipulate. You can assign / reassign the memory address that a pointer points to with very little effort. In git, you can also manipulate branches as if they were pointers. There are several ways to do this, too. You can use the git reset command, for example, to simply move a pointer from one location to another. To do this and to continue the analogy of pointers, think about a commit as a location in memory, and the commit ID is the address of that location.

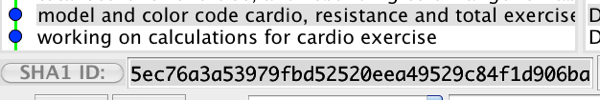

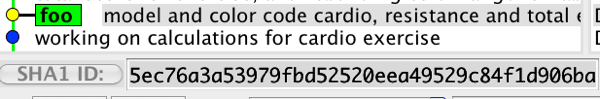

The selected commit in this screen shot would have an “address” of 5ec76a3… if we have an existing branch called “foo” and we want the foo branch to point to this commit, we can call git reset like this:

(foo) $: git reset 5ec76a3 --hard HEAD is now at 5ec76a3 model and color code cardio, resistance and total exercise

We now have our foo branch pointing at this commit.

There are several other commands that can manipulate pointers directly, too. Even the merge command will sometimes perform pointer manipulation on your branch instead of actually doing a merge. This is referred to as “tivo source control” or fast-forward merging. It happens when two branches are on the same timeline with no divergence, and the one that is further behind in the timeline is merged up to the one that is ahead in the timeline.

Additionally, most of the “Oops!” series of posts that I’ve done on git are nothing more than pointer manipulations in this manner. Not all of them of course, but many of them are.

Analogies Fall Apart, But Branches Are Pointers

Like all analogies, eventually the idea of a branch being a pointer to a memory address will fall apart. Even if a branch is nothing more than a pointer, it doesn’t actually point to a memory location. it points to a commit ID. Once you wrap your head around the idea of a named branch being a pointer, though, the realization of what it is pointing to can open a world of possibilities for how you think about and approach the use of git’s branches.