Git: Remotes, contributions, and the letter N

Here’s a few ways to think about Git and it’s distributed nature.

- You deal with multiples of repositories, not a single central repository

- Updates come from a remote repository, and changes are pushed to a remote; none of these repositories have to be the same

- Origin is the canonical name for the repository you cloned from

- Upstream is the canonical name for the original project repository you forked from

General pushing and pulling

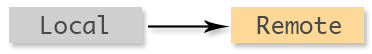

Pushing your changes to a remote: git push remote_name

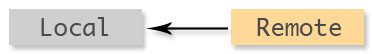

Pulling changes from a remote: git pull remote_name

Or if you want to rebase:

git fetch remote_name git rebase remote_name/branch

You can change your

branch.autosetuprebasetoalways, to make this the defaultgit pullbehaviour.

That’s all there is to moving commits around in Git repositories. Any other operations you perform are all combinations of the above.

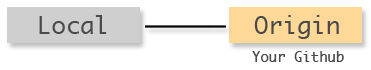

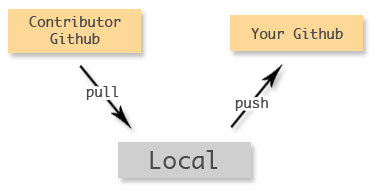

Github — personal repositories

When you’re dealing directly with Github, on a personal project or as the project owner, your repositories will look like this:

To push and pull changes between your local and your github repositories, just issue the push and pull commands with the origin remote:

git push origin git pull origin

You can set the defaults for these commands too, so the origin isn’t even necessary in a lot of cases.

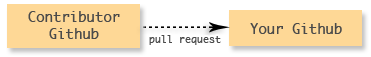

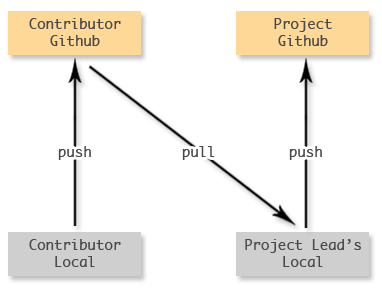

Github — receiving contributions

As a project owner, you’ll sometimes have to deal with contributions from other people. Each contributor will have their own github repository, and they’ll issue you with a pull request.

There’s no direct link to push between these two repositories; they’re unmanned. To manage changes from contributors, you need to involve your local repository.

You can think of this as taking the shape of a V.

You need to register their github repository as a remote on your local, pull in their changes, merge them, and push them up to your github. This can be done as follows:

git remote add contributor contributor_repository.git git pull contributor branch git push

Github — providing contributions

Do exactly as you would your own personal project. Local changes, pushed up to your github fork; then issue a pull request. That’s all there is to it.

Github — the big picture

Here’s how to imagine the whole process, think of it as an N shape.

On the left is the contributor, and the right is the project. Flow goes from bottom left, along the lines to the top right.

- Contributor makes a commit in their local repository

- Contributor pushes that commit to their github

- Contributor issues a pull request to the project

- Project lead pulls the contributor’s change into their local repository

- Project lead pushes the change up to the project github</ol> That’s as complicated as it gets.