Designing primary keys

When creating a primary key for a table, we have a few options:

- Composite key

- Natural key

- Surrogate key</ul> Each has their own advantages and disadvantages, but by and large I always wind up going with the last option.

Composite keys

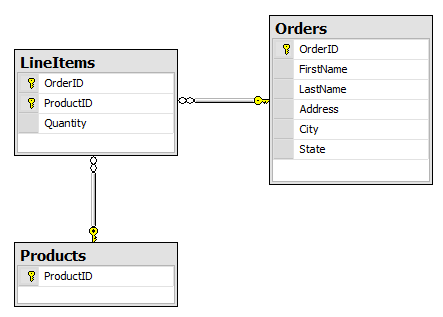

Composite keys are primary keys made up of multiple columns. For example, consider a system with and Order and LineItem table:

The LineItems table has an identity that is composed of two columns: the OrderID and the ProductID. This makes sense in that an Order can only have one LineItem per Product.

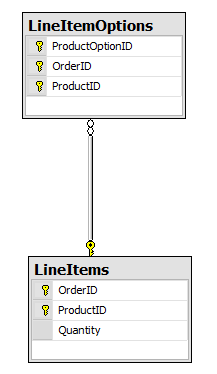

The problem happens when I need to make a table that has a foreign key relationship to the LineItems table:

Blech! Now our composite key is invading every table that relates to it. Order is a natural aggregate root, but what happens if we decide later down the line that a LineItem is a standalone concept?

I’ve seen this a few times in databases I’ve created and some legacy ones. You assume that a row’s identity is defined by its parent, but later it begins to have a life of its own.

Unless the table is a junction table (one that holds a many-to-many relationship), and it doesn’t have and attributes of its own, a single primary key is the safest bet.

Natural keys

Ugh.

Please don’t continue this (worst) practice going forward. Natural keys are keys with business uniqueness, such as Social Security Number, Tax ID, Driver’s License Number, etc.

Besides performance issues with data like these as keys, one thing to keep in mind is that an entity’s identity can never change, from now until the end of time.

Things like SSN’s and such are likely entered by humans. Ever mistype something? If something needs to be unique, there are other ways besides a primary key to ensure uniqueness.

Surrogate keys

Surrogate keys are computer-generated keys that likely have no meaning, or might never be shown to the end user. Typical types are seeded integers and GUIDs.

Personally, I prefer GUIDs as they’re guaranteed to only to be unique to the table, but globally unique (it’s in the name for pete’s sake!) Combed GUIDs provide comparable performance to integers or longs, as well as the added benefit that they can be created by the application instead of the database. GUIDs also play very nicely in replication scenarios.

You can still use natural key information, such as SSN, to identify or search for a particular record, but a surrogate key ensures uniqueness and performance.

Frankenstein keys

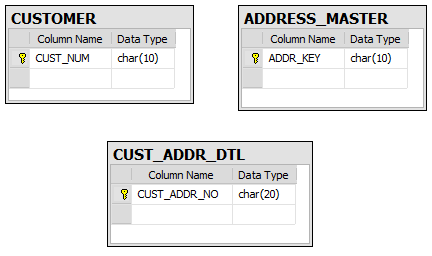

Unfortunately I have found another kind of primary key: the Frankenstein key. Here’s a small taste:

Hmmm…let’s see, a CUSTOMER table, an ADDRESS_MASTER table, and one table that should join the two together, the CUST_ADDR_DTL. But it doesn’t have any foreign key relationships to the two tables it should have, it has a cryptic CUST_ADDR_NO column instead.

Looking at the data reveals a mind-boggling design:

CUST_NUM ---------- 89480

- Natural key

ADDR_KEY ———- 441839

CUST_ADDR_NO

89480 441839 </pre>

[](http://11011.net/software/vspaste)

Wow. Fixed-length column values aren’t new, especially in databases ported from mainframes. The last value, instead of having two columns in a composite key, just jams both foreign key values into one single Frankenstein column.

Just about the ugliest thing I’d ever seen, until I saw a SELECT statement, with where clauses using string functions to parse out the individual values.

### Surrogate GUIDs by default

It doesn’t cost anything, and it’s the easiest and simplest choice to make going forward. Composite keys can still be represented as foreign keys and unique constraints, but it’s tough to add identity later.

Not to mention, domain models look pretty terrible and are quite brittle with composite keys. As any system is so much more than data it contains, why not go with surrogate keys, which give so much flexibility to your design?