Troubleshooting SQL index performance on varchar columns

Doing a deployment last night, I ran into an issue around indexing performance around SQL columns of type varchar. Varchar is the ANSI version of character data – storing as 8-bits, while nvarchar is Unicode, storing as 16 bits. For this database, we typically opt in for varchar, as it supports a US chain of retail stores, and has millions (sometimes hundreds of millions) of rows. Storage on a database like this is important, so we mind our strings.

I ran into a case recently where I was running a very simple query to find transactions by members. This table contained all in-store transactions for a nationwide retail chain. Not too bad of a query, the table has a lot of rows, but not a crazy number of 42 million rows for 18 months of production data. Something SQL Server should be able to handle without any problems whatsoever. So I ran a simple query:

SELECT * FROM [Transactions] WHERE [AccountId]=@1

This is more or less what came straight out of my ORM. However, the query was SLOOOOOOOW. As in minutes slow. First check, let’s look at the table to make sure the index is defined appropriately. We had this index:

CREATE NONCLUSTERED INDEX [IX_TransactionsAccountId] ON [dbo].[Transactions] ( [AccountId] ASC )

So far so good, we have an index defined, but why is my query so slow? I checked all the statistics and what not and found that the index seemed to work OK. I dropped down to SQL Management Studio to try the query out.

To my surprise, it was blazing fast. What was the difference? I used SQL Profiler to see what the actual query being sent down was. After a bit of an epiphany there, I ran these two queries:

SELECT * FROM Transactions WHERE AccountId = '9876543210987654' GO SELECT * FROM Transactions WHERE AccountId = N'9876543210987654'

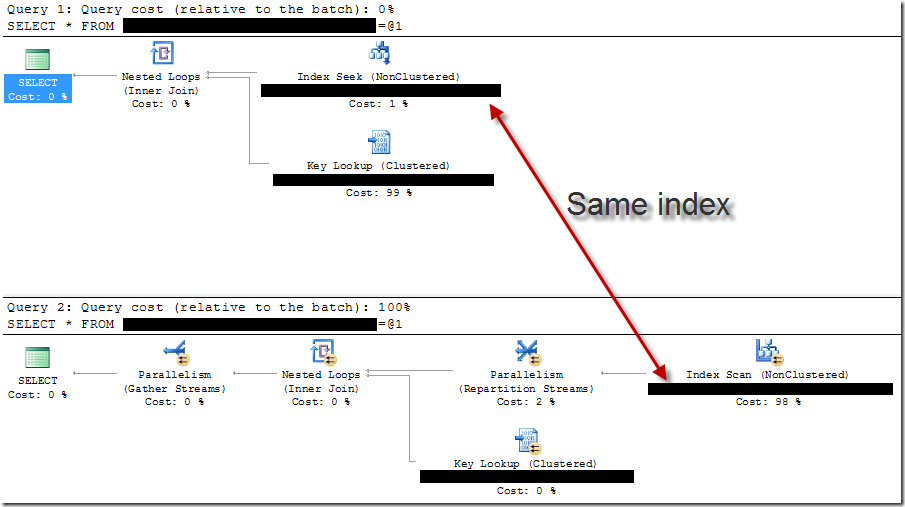

And wouldn’t you know it, the first query was fast and the second slow. But why was the second one so slow? And why did this matter? Looking at the execution plans in SSMS:

So seemingly identical queries, but the execution plans are much, much different! The difference between the two queries is the first uses ANSI strings, while the second uses Unicode strings. The first results in an index seek (very fast) while the second an index scan (absolutely horrible, sequential scanning). For each row, SQL Server would convert the index’s value to NVARCHAR, as seen in the index plan’s details around the predicate:

CONVERT_IMPLICIT(nvarchar(200),[dbo].[Transactions].[AccountId],0)=N'9876543210987654'

Of course it’s going to be slow! Every source value is converted to NVARCHAR, and then compared to the source value, instead of vice versa. This is because Unicode –> ANSI is lossy, and therefore not able to be implicitly converted. So the ANSI string has to be upconverted to Unicode.

Anyway, going to our ORM and forcing the SQL parameter type to be an ANSI string fixed the problem. And once we found this one, we found a dozen other places that we I had screwed up.

Lessons learned

One way to fix this would be to use all Unicode, all the time. For me, that makes sense for a lot of character data. But for data that really just happens to be character data, but actually originates from automated systems, it doesn’t make as much sense to make these Unicode. For tables with large numbers of rows, and indexes on character-based columns, space does matter. This is speaking from a person that has had databases run out of space, it can be a problem that I need to care about.

The other lesson is that ORMs aren’t a tool to hide the database, they’re there to abstract some pieces and encapsulate others. But it’s still imperative I know what is going on between my system and the database, no matter what form it takes.

And finally – everything performs great on a local database with 10 rows. If I can test queries that I know are going to scan anything besides a primary key, I can eliminate this problem before going to production and having to do an emergency deploy because the website was spinning.