Evolutionary Project Structure

I used to care quite a bit about project structure in applications. Trying to enforce logical layering through physical projects, I would start off a project by defaulting to building an app with at least two projects, if not more. Something like:

- Core

- UI

- Infrastructure

- Data Access

- etc etc

I’ve since moved completely away from this sort of project structure, mostly because it can devolve into arguments about what the right dependency directions are and so on. But for most systems I’ve seen, deciding about project structure is a waste of time and energy. Folders are just fine for layering, and you can always introduce projects when the need arises.

Instead, I LOVE the project structure of RaccoonBlog:

So what’s the project structure here? None!

Instead of layering using project structure, we just use folders. The domain model is in the Models folder. Infrastructure components are in the Infrastructure folder. Dogs and cats, living together, mass hysteria! Insane, right? Not at all.

Flatten your layers

What really makes this work is that there are no pointless abstractions like repositories or even DI containers to get in the way. It’s not a simple application, but it’s not terribly complex either.

One of the reasons why this works well is that the underlying architecture (RavenDB) clearly separates reads from writes. Writes go against aggregates realized as documents, and reads are clearly separated into RavenDB indexes. When your data access layer clearly separates things out this way, it makes it much easier to build a layered architecture on top without needing to resort to enforcement via projects. It’s called the “pit of success”.

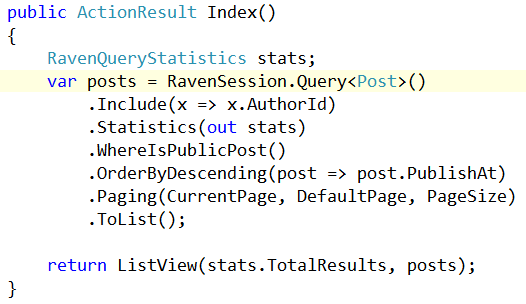

So what does a typical action look like? Let’s look at the action displaying posts:

*gasp* It’s data access directly in the controller! Where’s the repository? Who cares! This query is used in one and exactly one place, this one controller action. Any common query methods are abstracted into extension methods (the WhereIsPublicPost method).

This action is perfectly testable, as RavenDB supports an embedded mode. And it won’t force us to create repositories that are essentially violations of both the Interface Segregation Principle and command-query separation principle.

By eliminating unnecessary abstractions, we don’t have to invent physical layering to support those abstractions. I never liked the repository pattern, but my desire to abstract things forced me into building things like Query objects to abstract the above query. I argue that abstracting the above action merely obfuscates with indirection.

What about ViewModels? There’s a purpose-built ViewModel folder to hold those. What about infrastructure-specific usages/extensions? Inside the Infrastructure folder we have those extensions for each 3rd-party component in its own folder.

Explicit component usage

One mistake I see teams make over and over again is trying to abstract components. I find it OK to put facades in front of things like 3rd-party web services, but when it comes to infrastructure components, there’s really no need to abstract.

In the method above, RavenDB is used directly inside the controller action. If we wanted to move this code somewhere else, we would need to invent an abstraction to do so, likely a repository. Why misdirect? Just consume the component directly, so that you have the full usage of the component at hand, and you don’t tie one hand behind your back by pretending important and valuable features don’t exist.

Where this falls down is when a component doesn’t support a given layering/architecture. But even with NHibernate, I just use the ISession directly in the controller action these days. Why make things complicated?

Even worse would be to put an abstraction around ISession and pretend NHibernate doesn’t exist. That’s a quick path to a lot of additional infrastructure code where you have to re-invent features already present in your 3rd-party component.

However, if using the 3rd-party component is difficult (like ADO.NET code), then by all means provide a façade. Defer abstraction decisions until the need presents itself, and you’ll find yourself with a much more flexible application.

When complexity arises

This approach goes a long way until your application actually has enough complex behavior to warrant additional layering. We have two options here:

- Reduce complexity in requirements

- Realize complexity explicitly in your model

If your application is complex, you might be able to work to reduce the complexity in the actual requirements. This is the ideal solution, as complexity in business requirements is often a smell for the need for simplicity. I often see this when business owners can’t explain a feature to me the same way twice.

If that fails, model the complexity explicitly. This is where techniques in the DDD book and patterns books help. It’s still a flat structure, but I might have to do a little more organization to keep rules separate from the rest of the application.

And if two applications need to use the same code, then by all means, introduce projects to share!

Layering versus structure

For me, it all comes down to logical versus physical architecture. Architectural styles aren’t project structure layouts. They’re simply a way to describe roles, responsibilities, and layers. Forcing ourselves into project structures and component ignorance just gives rise to more and more code needed to prop up our invented abstractions.

So check out RaccoonBlog, enjoy its elegance and simplicity. You might disagree with certain decisions, but it’s certainly easy to understand, extend and evolve.