Estimation scoping

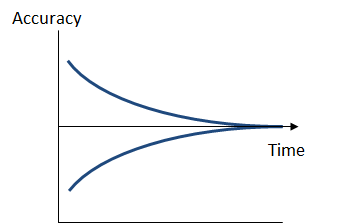

Read any book about estimation and you’ll probably see a picture of this:

This is the cone of uncertainty, a measure of the accuracy of our estimation of effort as we get closer to finishing work. Very close to finishing, we have a very good idea of how much is left. As we move away from the time to completion, the variance of our estimates increases drastically.

Breaking work into iterations helps combat our uncertainty, by forcing ourselves to estimate work in time periods we as developers can actually understand. Breaking down work into small, manageable pieces also helps combat our uncertainty, and iterations are a common tool to force this.

The reasons for the growing uncertainty are many, but a lot of it has to do with the complexity of building software. Building software isn’t like building a house – we don’t have a fixed budget and scope, and can simply throw people at the problem or lower quality. Nor are we stamping out many houses that are 98% alike, with slight variations in floor plans and the “finish” of a house.

However, in most software projects, there are a few absolutes, budget being a major one. So we have a fixed budget, usually a fixed set of people (salaries being the consumer of the budget), and very often, a fixed deadline.

Given all of this, how can we accurately estimate what “done” is?

Estimation techniques

I see a lot of different estimation techniques these days, from group estimation, to fibonacci sequences, and t-shirts. The basic goals remain the same:

- How much will this feature cost?

- When will we be done?

These are two very different questions, however. One looks at individual features, and the other attempts to look at all remaining work to decide when we’ll be done. So I see several different techniques tried:

- Estimate in hours (time/cost)

- Estimate in points (relative complexity)

- Estimate in t-shirt sizes (assigned budget)

When we estimate in hours, we’re trying to get an absolute cost, as well as set expectations of when work will be done. For points, we’re trying to set some expectation of relative complexity from one feature/story to another. For more amorphous sizing, it can be though more of sizing of a scale where we’re just trying to estimate the assigned budget we’ll allot to that item.

The mistake I see a lot of teams make is ignoring the cone of uncertainty and trying to use the wrongly estimation measurement for the wrong scope of item estimated. But we can fix that easily!

Reversing the cost question

Let’s just get this one out of the gate: It is impossible to fix a date far in the future, and have absolute certainty of exactly what set of features will be delivered. It’s also impossible to define a large set of features (large being anything that can be delivered > 6 months or so), and have any certainty of a date of delivery.

If we can’t know either of these with certainty, we should stop asking these questions. And if you’re getting asked these questions as a developer, don’t answer with a number or a date!

If I’m asked “how long will it take to replace legacy system ABC that’s been in development for 10 years”, my reaction is not to try and build out hourly estimates. Instead, I dig deeper into what the parameters for success are. Is success replacing every feature, as-is? Is it rolling out a new customer to the new platform, leaving the existing ones there? It it to merely change technology stacks/platforms?

Once we know our goals, the next question is – how much are we willing to spend to make this happen? Often the question comes back to the developers – well how much will this cost? Cost is hours, hours are estimates, and now we’re back in the original problem of our estimates are not being measured with the appropriate scope.

Scoping estimates

As we break down work into actionable items for developers to work on, I like to scope items based on the cone of uncertainty. Instead of using the same measure for every level of uncertainty, I use different measurements for different levels of uncertainty:

- Epics/themes – T-shirt sizes (S, M, L, XL AND NO LARGER)

- Stories – points (1, 2, 3, 5, 8 AND NO LARGER)

- Tasks – hours (1, 2, 4, 8 AND NO LARGER)

The “and no larger” is critical. If any item becomes too large, it becomes too much inventory, and very expensive to move through the release pipeline. So how does story point relate to a task? It doesn’t! How does a t-shirt size relate to a story point? It doesn’t! So let’s not try.

Instead, let’s recognize these as what they are – estimates. Estimates are not an invoice.

By using different measurements based on uncertainty, we break the cycle of management assuming more certainty than exists. A 100-point story is not 10 10-point stories. Instead, it’s a story that’s way too large to estimate relative to other stories with any certainty.

Back to the original problem – how do we know how much it will cost to build some arbitrarily large system or rewrite an existing system? Be honest – it’s not that “I don’t know”, the truth is “it’s impossible to know with any certainty”. If the budget is fixed, scope must be flexible. If the scope is fixed, budget must be flexible.

Estimations are wrought with risks and uncertainty. The only way to eliminate these risks are not to estimate in detail all work needed to be done – that’s a waste of time. Instead, we focus on which we want to fix – budget or scope – and estimate and measure how quickly, based on each measurement, work moves through the pipeline. We then use those burndown rates to adjust either scope or budget.