10 Lessons from a Long Running DDD Project – Part 2

In Part 1 of this 2-part series, I walked through some lessons learned from the first incarnation of our project. The original project I’d still qualify as a success, in that it was delivered on-time, within budget, and is still under active development today. But we learned a lot of lessons from that project, and were lucky enough to have another crack at it so to speak when we started a new project, in the almost exact domain, but this time the constraints were quite a bit different.

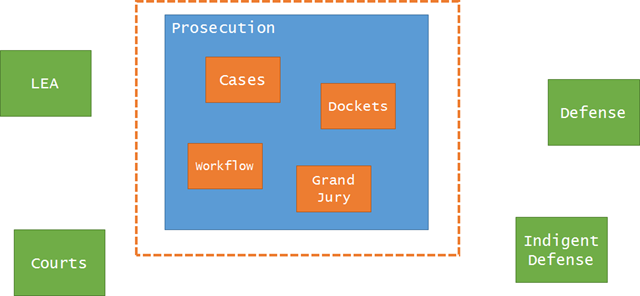

In the first project, we targeted everyone that could possibly be involved with the overall process. This wound up to be a dozen state agencies and countless other groups and sub-groups. Quite a lot of contention in the model (also a great reason why you can never have a single master data model for an entire enterprise). We felt good about the software itself – it was modular and easy to extend, but the domain model itself just couldn’t satisfy all the users involved, only really a subset.

The second project targeted only a single aspect of the original overall legal process – the prosecution agency. Targeting just a single group, actually a single agency, brought tremendous benefits for us.

Lesson 6: Cohesiveness brings greater clarity and deeper insight

Our initial conversations in the second project were somewhat colored by our first project. We started with an assumption that the core focus, the core domain would be at least the same as the monolith, but maybe a different view of it. We were wrong.

In the new version of the app, the entire focus of the system revolves around “cases”. I know, crazy that an app built for the day-to-day functions of a prosecution agency focuses centrally on a case:

Once we settled on the core domain, the possibilities then greatly opened up for modeling around that concept. Because the first app only tangentially dealt with cases (there wasn’t even a “Case” in the original model), it was more or less an impedance mismatch for its users in the prosecution agency. It was a bit humbling to hear the feedback from the prosecutors about the first project.

But in the second project, because our core domain was focused, we could spend much more time modeling workflows and behaviors that fit what the prosecution agency actually needed.

Lesson 7: Be flexible where you need to, rigid in others

Although we were able to come to a consensus amongst prosecution agencies about what a case was, what the key things you could DO with a case were and the like, we couldn’t get any consensus about how a case should be managed.

This makes a lot of sense – the state has legal reporting requirements and the courts have a ton of procedural rules, but internal to an agency, they’re free to manage the work any way they wanted to.

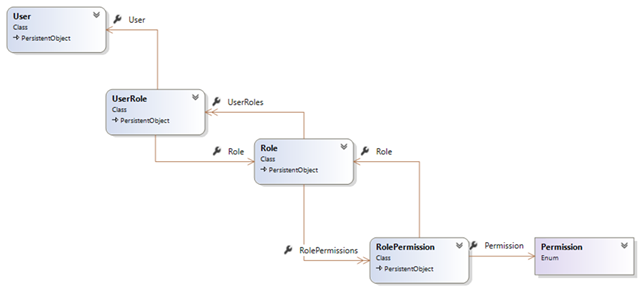

In the first system, roles were baked in to the system, causing a lot of confusion for counties where one person wore many different hats. In the new system, permissions were hard-coded against tasks, but not roles:

The Permission here is an enum, and we tied permissions to tasks like “Approve Case” and “Add Evidence” and “Submit Disposition” etc. Those were directly tied to actions in our application, and you couldn’t add new permissions without modifying the code.

Roles (or groups, whatever) were not hardcoded, and left completely up to each agency how they liked to organize their work and decide who can do what.

With DDD it’s important to model both the rigid and flexible, they’re equally important in the overall model you build.

###

Lesson 8: Sometimes you need to invent a model

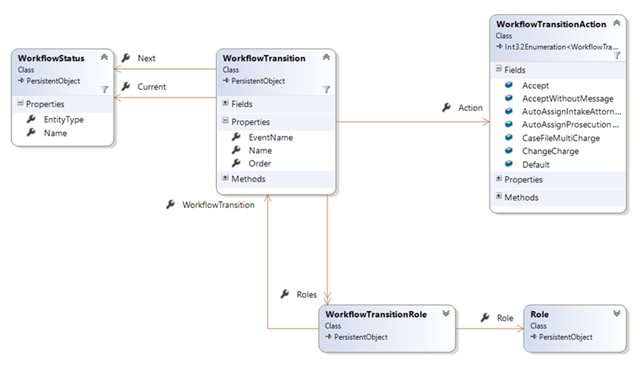

While we were able to model quite well the actions one can perform with an individual case, it was immediately apparent when visiting different county agencies that their workflows varied significantly inside their departments.

This meant we couldn’t do things like implement a workflow internal to a case itself – everyone’s workflow was different. The only thing we could really embed were procedural/legal rules in our behaviors, but everything else was up for grabs. But we still wanted to manage workflows for everyone.

In this case, we needed to build consensus for a model that didn’t really exist in each county in isolation. If we focused on a single county, we could have baked the rules about how a case is managed into their individual system. But since we were building a system across counties, we needed to build a model that satisfied all agencies:

In this model, we explicitly built a configurable workflow, with states and transitions and security roles around who could perform those transitions. While no individual county had this model, it was the meta-model we found while looking across all counties.

###

Lesson 9: Don’t blindly follow pattern advice

In the new app, I performed an experiment. I would only add tools, patterns, and libraries when the need presented itself but no sooner. This meant I didn’t add a repository, unit of work, services, really anything until an actual pain surfaced. Most of the DDD books these days have prescriptive guidance about what your domain model should look like, how you should do repositories and so on, but I wanted to see if I could simply arrive at these patterns by code smells and refactoring.

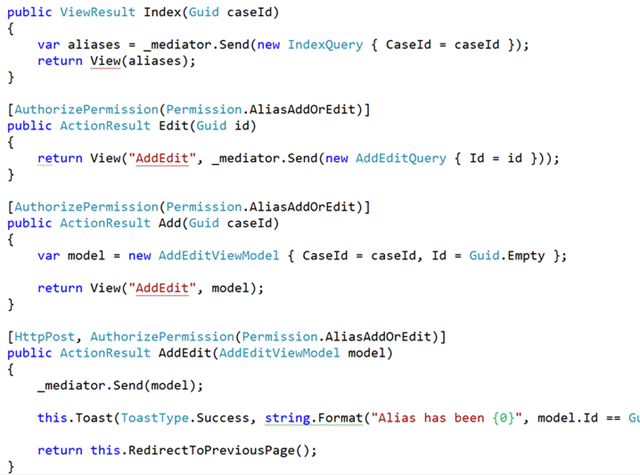

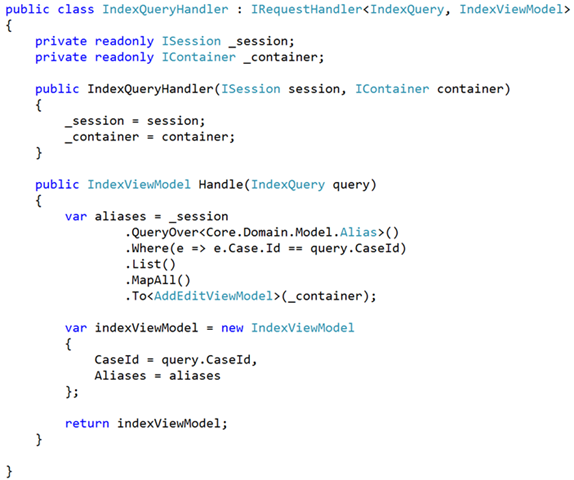

The funny thing is, I never did. We left out those patterns, and we never found a need to put them back in. Instead, we drove our usage around CQRS and the mediator pattern (something I’ve used for years but finally extracted our internal usage into MediatR. Instead, our controllers were pretty uniform in their appearance:

And the handlers themselves (as I’ve blogged about many times) were tightly focused on a single action, with no need to abstract anything:

I’ve extended this to other areas of development too, like front-end development. It’s actually kinda crazy how far you can get without jQuery these days, if you just use lodash and the DOM.

Lesson 10: Microservices and anti-corruption layers are your friend

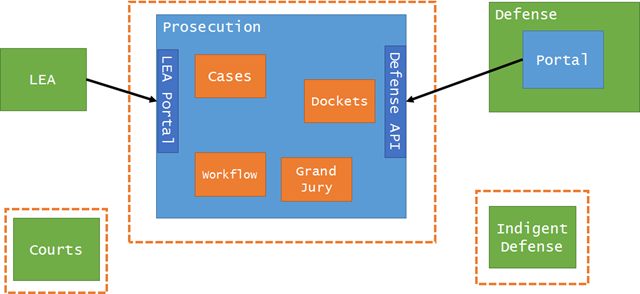

There is a downside to going to bounded contexts and away from the “majestic monolith”, and that’s integration. Now that we have an application solely dealing with one agency, we have to communicate between different applications.

This turned out to be a bit easier than we thought, however. This domain existed well before computers, so the interfaces between the prosecution and external parties/agencies/systems was very well established.

This was also the section of the book skipped the most, around anti-corruption layers and bounded contexts. We had to crack open that section of the book, dust it off, smell the smell of pages never before read, and figure out how we should tackle integration.

We’ve quite a bit of experience in this area it turns out, so it was really just a matter of deciding for each 3rd party what kind of integration would work best.

For some 3rd parties, we could create an entirely separate app with no integration. Some needed a special app that performed the translation and anti-corruption layer, and some needed an entirely separately deployed app that communicated to our system via hypermedia-rich REST APIs.

Regardless, we never felt we had to build a single solution for all involved. We instead picked the right integration for the job, with an eye of not reinventing things as we went.

###

Conclusion

In both cases, I’d say both our systems were successful, since they shipped and are both being used and extended to this day. With the more tightly focused domain in the second system we were able to achieve that “greater insight” that the DDD book talks about.

In case anyone wonders, I intentionally did not talk about actors or event sourcing in this series – both things we’ve done and shipped, but found the applicability to be limited to inside a bounded context (or even more typically, a corner of a bounded context). Another post for another day!