CQRS/MediatR implementation patterns

Early on in the CQRS/ES days, I saw a lot of questions on modeling problems with event sourcing. Specifically, trying to fit every square modeling problem into the round hole of event sourcing. This isn’t anything against event sourcing, but more that I see teams try to apply a single modeling and usage strategy across the board for their entire application.

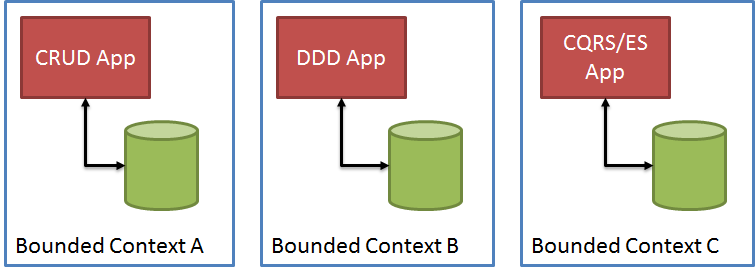

Usually, these questions were answered a little derisively – “you shouldn’t use event sourcing if your app is a simple CRUD app”. But that belied the truth – no app I’ve worked with is JUST a DDD app, or JUST a CRUD app, or JUST an event sourcing app. There are pockets of complexity with varying degrees along varying axes. Some areas have query complexity, some have modeling complexity, some have data complexity, some have behavior complexity and so on. We try to choose a single modeling strategy for the entire application, and it doesn’t work. When teams realize this, I typically see people break things out in to bounded contexts or microservices:

With this approach, you break your system into individual bounded contexts or microservices, based on the need to choose a single modeling strategy for the entire context/app.

This is completely unnecessary, and counter-productive!

A major aspect of CQRS and MediatR is modeling your application into a series of requests and responses. Commands and queries make up the requests, and results and data are the responses. Just to review, MediatR provides a single interface to send requests to, and routes those requests to in-process handlers. It removes the need for a myriad of service/repository objects for single-purpose request handlers (F# people model these just as functions).

###

Breaking down our handlers

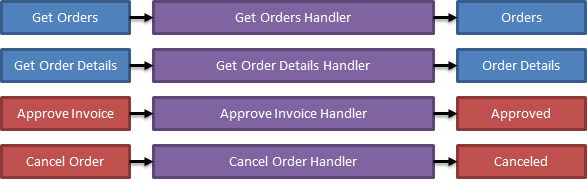

Usage of MediatR with CQRS is straightforward. You build distinct request classes for every request in your system (these are almost always mapped to user actions), and build a distinct handler for each:

Each request and response is distinct, and I generally discourage reuse since my requests route to front-end activities. If the front-end activities are reused (i.e. an approve button on the order details and the orders list), then I can reuse the requests. Otherwise, I don’t reuse.

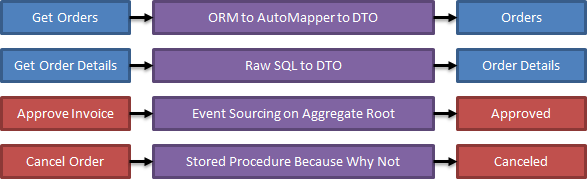

Since I’ve built isolation between individual requests and responses, I can choose different patterns based on each request:

Each request handler can determine the appropriate strategy based on *that request*, isolated from decisions in other handlers. I avoid abstractions that stretch across layers, like repositories and services, as these tend to lock me in to a single strategy for the entire application.

In a single application, your handlers can execute against:

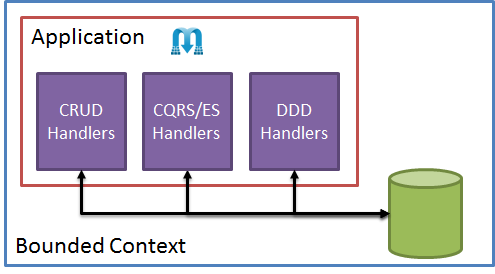

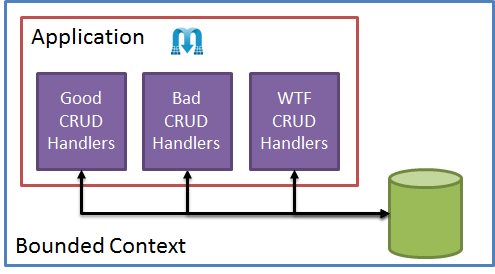

It’s entirely up to you! From the application’s view, everything is still modeled in terms of requests and responses:

The application simply doesn’t care about the implementation details of a handler – nor the modeling that went into whatever generated the response. It only cares about the shape of the request and the shape (and implications and guarantees of behavior) of the response.

Now obviously there is some understanding of the behavior of the handler – we expect the side effects of the handler based on the direct or indirect outputs to function correctly. But how they got there is immaterial. It’s how we get to a design that truly focuses on behaviors and not implementation details. Our final picture looks a bit more reasonable:

Instead of forcing ourselves to rely on a single pattern across the entire application, we choose the right approach for the context.

Keeping it honest

One last note – it’s easy in this sort of system to devolve into ugly handlers:

Driving all our requests through a single mediator pinch point doesn’t mean we absolve ourselves of the responsibility of thinking about our modeling approach. We shouldn’t just pick transaction script for every handler just because it’s easy. We still need that “Refactor” step in TDD, so it’s important to think about our model before we write our handler and pay close attention to code smells after we write it.

Listen to the code in the handler – if you’ve chosen a bad approach, refactor! You’ve got a test that verifies the behavior from the outermost shell – request in, response out, so you have a implementation-agnostic test providing a safety net for refactoring. If there’s too much going on in the handler, push it down into the domain. If it’s better served with a different model altogether, refactor that direction. If the query is gnarly and would better suffice in SQL, rewrite it!

Like any architecture, one built on CQRS and MediatR can be easy to abuse. No architecture prevents bad design. We’ll never escape the need for pull requests and peer reviews and just standard refactoring techniques to improve our designs.

With CQRS and MediatR, the handler isolation supplies the enablement we need to change direction as needed based on each individual context and situation.