Introduction To Composite JavaScript Apps

One of the projects I’m working on for a client makes heavy use of Backbone.js to run functionality in the browser. The back end system is built on ASP.NET MVC with an evolving CQRS based architecture. In order to keep the front end as flexible as possible and be able to work with the various back end pieces that are being put in place, I need to follow many of the same patterns and principles in my JavaScript.

Functional Areas Of A JavaScript App

As our applications get larger and larger, it’s important to decouple the various functional areas. Decoupling them – or rather, coupling them correctly – allows much greater flexibility by letting us change how each functional works, without affecting the other areas.

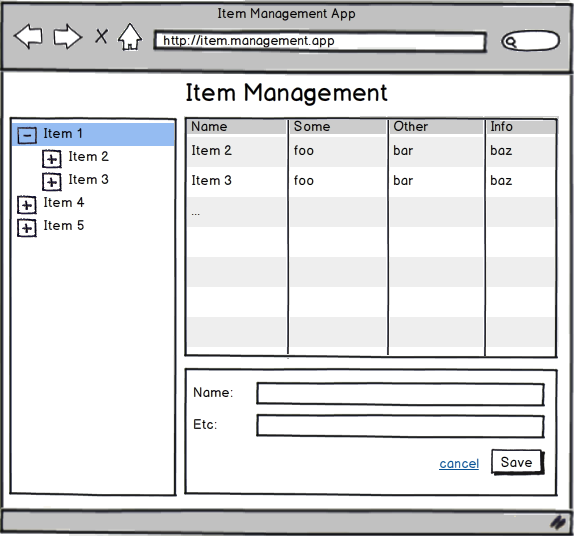

As an example of functional areas, here’s a wireframe of something similar to what I’m currently working on:

The application shown here is a very simple item management app. On the left, you have a tree with a hierarchy of items. On the top right, you have a grid view to show the child items of the item that was selected in the tree. On the bottom right, you have an add/edit form.

The important thing to note here is that each of the primary control groups is a functional area of the app and needs it’s own modularized JavaScript code. That is, the treeview, the grid and the add/edit form are all separate areas of functionality within this application. Each of these areas of functionality should be placed in their own file and modularized / decoupled so that none of them knows about the other directly. Doing this will make the over all application easier to manage and maintain, allowing greater flexibility in adding and removing features.

There are likely hundreds of ways that you could build this application, but many of them would lead to large monolithic beasts of unmaintainable code. In recent years though, maintainable and scalable JavaScript has become a hot topic, and there are some good patterns and architectures that have emerged as a result.

I’ve only just begun to explore these patterns and architectures in the last few months, but I wanted to share my perspective and what I’m currently doing.

JavaScript Modules

A JavaScript module isn’t a special construct or keyword in the language itself. Rather, it’s a way to take advantage of functions closures, to create scope. The core of a JavaScript module is usually an “immediate function”:

The use of the parenthesis around the function definition allows the function to be returned, ready to go (if you forget the parenthesis around the function, you’ll get a syntax error).The second pair of parenthesis immediately execute the returned function. The result can be assigned to a variable, which becomes a reference to the module’s public API (if anything was returned).

There’s been a lot of talk around the web about JavaScript modules already, so I won’t go in to much more detail here. Two of the more recent articles are focused specifically on Backbone, and I highly recommend reading them:

Organizing Your Backbone.js Applications With Modules – This article from Bocoup.com covers the basics of file organization and creating a way to easily reference your modules from other modules, using strings as names.

Organzing your application using Modules (Require.js) – This article from BackboneTutorials covers much of the same ground, but does it using the Require.js framework.

Of course, there’s more than these two methods of modularizing your JavaScript code. You don’t have to stick with the patterns that someone else shows you (include what I’m going to show you) but it’s always a good idea to learn from what others are doing, even if you don’t stick with it.

External / Shared Code

In spite of our desire to separate each of the functional areas of the application, there is a high likelihood that they will need to talk to each other and have access to some of the same code. You’ll also want to have access to some external libraries, such as jQuery, Underscore.js, Backbone.js, or any of a number of other libraries and tools that your code uses.

The usual method of doing this with a plain JavaScript module is to pass the dependencies into the module function. For example, if you need jQuery and Backbone in your module, you might add a $ and Backbone parameters to your module definition. Then you would pass the references to them when you execute the module function:

The same thing applies to your own modules and libraries. If you have a module defined somewhere else and you know it will be available before the module your currently working on is loaded, you can pass in a reference like this.

(You should also know that once you start heading down this path, you may want to think about using asynchronous module definitions: AMDs. Tools such as RequireJS make AMDs easier to deal with by handling the dependency management, module definition and other common tasks for you.)

Module Initialization

Writing a bunch of modules in a decoupled manner is great, but it introduces another problem: initialization. Most JavaScript applications have some public API that you call when you want to initialize the app and make everything run. If you’re building your app in a modular manner, you don’t want to have to call a separate public API for every module in your system. This would become a nightmare over time by requiring a lot of app initialization code, and worse.

To work around this problem, modules need to have some sort of initialization code in them. Module frameworks like RequireJS have this built in to them. In the app I’m writing, I’m not using RequireJS or any other module frameworks, so I wrote my own registration. It’s pretty simple when it comes down to it. Since every module I write for my app receives an app object, I attached a `addInitializer` function to it. This allows each module to add it’s own initializer code as a callback function, like this:

The application object keeps track of all the callbacks that were passed in to the `addInitializer` function. When the overall application is being initialized, a call to the app object’s `initialize` method will loop through each of the registered module initializers and call them. Each module gets to do it’s own thing and spin itself up.

Event Driven Architecture

Modules are great for organizing your code, but present a challenge when you realize that you need these modules to communicate with each other. Your code is now separated into different files, encapsulated in different modules, and generally unable to make direct calls in to your other modules and objects like you may be used to. Don’t worry, though. You’re only bumping in to the next steps of decoupling your applications correctly.

There are many different ways that you can solve this problem, of course. One of my favorite ways is the use of an event aggregator. I’ve blogged about the use of an event aggregator with Backbone already. If you need an introduction to the idea, check out that post and some of my many other Winforms / Application Controller posts. The benefit of an event aggregator in this case, is that is gives you a simple, decoupled way to facilitate communication between your modules.

To get started, you need to have a module or other object that is defined prior to any other modules being defined. This object needs to be passed in to each of the modules that you’re defining, so that these modules can have access to the event aggregator. In my app, I put the event aggregator directly on the top level application namespace, and then pass the namespace object into each of my modules:

Now each of my modules can bind to and trigger events from the event aggregator. This allows one module to send notification of something that happened, without having to know specifically which parts of the application are going to respond to that notification, or how.

One thing you need to think about, in advance, is what events you’re going to be triggering through the event aggregator. It’s a good idea to have thought through this at least a little bit, so that you don’t end up with a giant mess of similar and undocumented events. I made this mistake and paid for it when I couldn’t figure out which events needed to be fired, when. By taking the time to think through which events needed to be fired when, though, I was able to plan the communication between my modules, document the catalog of events, and clean up the number of events that were being used. Having this documented is important so that other developers (or you, a month from now) can see if there’s already an event that has the semantics they need, when writing new code.

Runtime Packaging

Once you have all of these pieces in place, you need to pull them all together and send them down to the browser. You could go ahead and reference each individual JavaScript file from your HTML. This would technically work, but would cause performance problems for the browser and end user. Each file that your reference requires another request to the server, which requires more time to download and potentially blocks another part of the app from loading or running (once you reach the magic limits of how many requests a browser is allowed to make).

To solve this problem, you need to use a packaging system. These systems will take all of the files that you specify, bundle them into a single file, optionally minify the whole thing and then provide that one file as a single resource for the browser. RequireJS has an associated optimizer to handle this. Rails 3.1 has the asset pipeline to do this. There’s the ruby gem “Jammit” which also does this for Ruby / Rails app (and Sinatra, etc). In .NET land, there’s several available including SquishIt. And there are still more in these and in other languages and environments.

If you don’t make use of one of these packaging tools, you’re going to cause problems for you users. Pick one, learn it, use it.

So Much More: Resources

At this point, you should be able to wire together a very simple, composite JavaScript application. This is only the tip of the iceberg, though. There’s so much more to writing well organized, scalable, modularized and composite JavaScript applications. If you would like to continue down this path, be sure to read the posts I’ve linked to. You’ll also want to check out these resources:

- Scalable JavaScript Application Architecture – and the framework that was produced with it, on GitHub:

- https://github.com/eric-brechemier/lb_js_scalableApp (Thanks to Aaron Mc Adam for the tip on the slides!)

- Patterns For Large Scale JavaScript Application Architecture – a great resource for getting ideas on architecture and why you want to

- JavaScript Patterns – my favorite JavaScript book. It has provided more valuable information on JS patterns and implementation ideas than any other book or resource I’ve read (note: it’s not specifically about architecture, but you need to know these patterns to create good architecture).

- Essential JavaScript Design Patterns For Beginners – this is a very comprehensive, but very large single page, list of patterns and implementations

- JavaScript Architecture – Aaron Hardy has great series on JS architecture. It starts simple and gets more and more detailed, providing a tremendous amount of links and information.

I’m sure there are additional resources as well. If you have any favorite resources for JavaScript architecture and composite application design, please post them in the comments!