Sometimes It’s Better To Use A Ruby Hash Than Create A Custom Class

The Eloquent Ruby book talks about the use of hashes and arrays vs classes. One of the things it covers is how hashes and arrays are often used by experienced ruby developers in place of custom classes. Coming from a .NET world, this would be the equivalent of using the generics collections like List

One of the things that I’m slowly starting to learn is that excess nil checks are a sign that I’m doing something wrong. In this case, a sign that I may be creating too many layers of models and abstractions. I’m not saying I should never create custom models. But I think there are times when I can simplify my code significantly by using a hash and flattening my code structure into it, instead of relying on custom models.

An Example: A Hash Vs A Class, Used In A View

Examine the following code from a HAML based view in a rails app. and pay attention to the ‘lipids’ and ‘genetics’ variables and how they are used.

- lipids = decision_panel.lipids

- genetics = decision_panel.genetics

%ul

%li

%p Apo E

= scored_value_tag genetics[:apo_e]

%li

%p LDL:

= scored_value_tag lipids.vldl if lipids

There’s nothing terribly magical or special about this code or the use of either of these variables. It does, however, illustrate a subtle yet potentially important distinction between how the lipids and genetics attributes were implemented on the decision_panel class and these differences can have a profound impact on the code that uses them.

The obvious difference between lipids and genetics is that the lipids is a custom class implementation while genetics is a hash. Even without seeing the implementations this is fairly apparent by the syntax. The call to lipids.vldl is not a standard method name on any standard ruby objects. It’s specific to the domain that I’m working in (health care). This gives an indication of the vldl attribute being defined in a class somewhere. Contrast that to the use of generics, which accesses a value via the named key of a hash. It’s very likely that the genetics variable is a hash, given the syntax used.

Nil Checks Can Cause Ugly Things

This is one of the lessons that I’ve been learning the hard way. Look at the difference in use between lipids and genetics in the above code. The line that calls into lipids has an “if lipids” check at the end of it. This is necessary because the lipids variable may be nil. The implementation of the decision_panel.lipids attribute is doing something that may or may not return a valid lipids class. In this specific case, it’s loading data from the database based on some criteria. If that criteria fails to find anything to load, then a nil will be returned.

class DecisionPanel

def lipids

Lipids.where(:some_criteria => "some value")

end

end

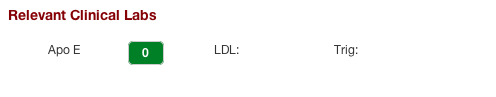

It gets worse when we look at what this does to the UI, too. The “if lipids” check at the end of the line causes the entire line of code to not produce anything if the lipids variable is nil. By contract, the call into a hash to get a value may return nil but that nil return value will never cause the line of code to not be executed. When we look at the output of this type of code in our application, we can easily end up with something that looks like this:

(In the off-chance that you actually know what “Apo E” is, please ignore the invalid value of “0”. This is just test data for my dev evironment.)

It may be ok for your screens to end up looking like this, but I don’t consider this to be good practice. Having a label for nothing on the screen tends to make users think there is something wrong with the system. It would be much better to have the LDL label showing “N/A” or something equivalent if there is no LDL data to show. However, the way we implemented our models make this less than beautiful in our code.

In order to show “N/A” we have to do some nil checks. Remember, though, that this LDL line of code is already doing a nil check to make sure the lipids variable is not nil. The verbose way of making this work would be an if-then statement around the code

- if lipids = scored_value_tag lipids.vldl - else = scored_value_tag "N/A"

This code is functional, but it is getting pretty verbose and also duplicating a little bit by having to call the ‘scored_value_tag’ method on multiple lines. We can clean this up a little, though

- vldl = (lipids.vldl if lipids) || nil = scored_value_tag vldl || "N/A"

The first line does all of the if-then checks for us and either assigns vldl to the vldl value or to nil if the lipids variable doesn’t exist. There are actually two separate if-then statements tacked together into this one line, to ensure that we always have a variable to use. If we don’t do this, then we could end up with an exception being thrown when we try to use vldl on the next line.

| The next line consolidates what was previously two separate calls to scored_value_tag into one call. It also contains an if-then statement wrapped up in the ‘ | ’ or statement to either provide the vldl variable or if that variable is nil, to provide “N/A” to the scored_value_tag method. |

… that’s 3 if-then statements composed in two lines of code, all surrounding nil checks. That’s a lot of nil checks just to get an “N/A” blob of text to show up in a web page, and quite frankly, a bunch of ugly code (that I’m guilty of writing over and over and over again).

One way this can be remedied is by using the null object pattern in the decision_panel.lipids method. We could have that method always return an object, even when there was no object found, and provide some default behavior to say “N/A” instead of providing an actual value. This may be a good option for you and your scenario. In my case, though, the use of a null object pattern is a little overkill.

In my case, I am starting to see this type of code as …

A Sign That You May Want A Hash Instead

Let’s look at the aggregate code that we’ve ended up with, having implemented the various nil checks from the previous examples. At the same time, let’s add in the code that is needed to produce the same “N/A” value if the genetics code return a nil value:

- lipids = decision_panel.lipids

- genetics = decision_panel.genetics

%ul

%li

%p Apo E

- apo_e = genetics[:apo_e] || "N/A"

= scored_value_tag apo_e

%li

%p LDL:

- vldl = (lipids.vldl if lipids) || nil

= scored_value_tag vldl || "N/A"

Tell me, which of those would you rather read when you first encounter this view in the rails app? It’s a pretty easy choice in my book. The use of a hash in this case, has removed 2 out of 3 of the nil checks. The code is significantly easier to read and understand, and easier to modify because there are not a bunch of edge-case nil checks that have to be made.

How, then, do we recognize when it would be easier and/or better to use a hash than to use a custom class? In this case, the excessive nil checks in the code are a sign that we’re doing something wrong. However, there are multiple ways to solve this, including the null object pattern I mentioned previously.

The real sign that this is probably better off as a hash is when we look at the implementation of the lipids class. For effect, I’m posting the entire class, unedited. Ignore the methods and modules that you don’t recognize – just know that they are a part my system and they do what I need.

class Lipids

include DataParser

def initialize(obr_segment)

@obr = obr_segment

end

def total

value = get_obx_value @obr, "0058-8"

@scored_total ||= ScoredValue.new(value, :lipids_total)

end

def hdl

value = get_obx_value @obr, "0059-6"

@scored_hdl ||= ScoredValue.new(value, :lipids_hdl)

end

def hdl_percentage

value = get_obx_value @obr, "1764-0"

@scored_hdl_percentage ||= ScoredValue.new(value, :lipids_hdl_percentage)

end

def ldl_calc

value = (total.value.to_f - (hdl.value.to_f + vldl.value.to_f)).to_s

@scored_ldl_calc ||= ScoredValue.new(value, :lipids_ldl_calc)

end

def triglycerides

value = get_obx_value @obr, "0155-2"

@scored_triglycerides ||= ScoredValue.new(value, :lipids_triglycerides)

end

def vldl

value = get_obx_value @obr, "0505-8"

@scored_vldl ||= ScoredValue.new(value, :lipids_vldl)

end

def non_hdl_total

value = total.value.to_f - hdl.value.to_f

@scored_non_hdl_total ||= ScoredValue.new(value, :lipids_non_hdl_percentage)

end

def non_hdl_percentage

value = (non_hdl_total.value.to_f / total.value.to_f) * 100

value.to_i.to_s

end

def ldl_hdl_ratio

value = get_obx_value @obr, "0253-5"

@scored_ldl_hdl_ratio ||= ScoredValue.new(value, :lipids_ldl_hdl_ratio)

end

end

| Notice that there are 9 methods in this class that all basically do the same thing (with a small amount of variation). Each of these methods is calculating a value and then storing that value in an instance variable. The instance variable caches itself against multiple calls by using the | = syntax to only create itself if it doesn’t exist already. |

The end result of this class definition is that I now have a way to access a just-in-time calculated, cached value by name. Does that sound familiar at all? I hope it does, because with the exception of JIT calculation, I just described a hash: “A Hash is a collection of key-value pairs.” (from Ruby-Doc.org).

Now compare the Lipids class with the code that builds the genetics hash:

def genetics

@genetics ||= {

:apo_e => ScoredValue.new(lab.apo_e, :apo_e),

:apo_b => ScoredValue.new(lab.apo_b, :apo_b),

:lp_a => ScoredValue.new(lab.lp_a, :lp_a),

:nt_pro_bnp => ScoredValue.new(lab.nt_pro_bnp, :nt_pro_bnp),

:kif_6 => ScoredValue.new(lab.kif_6, :kif_6)

}

end

This code does essentially the same thing (without a calculation, though that would be simple to add to this code) but does it with a hash instead of a custom class. There is far less code to read, even if you account for the calculations that need to be done, and it’s generally easier to see that this is just access to a named set of value. This code also eliminates the desire to have an explicit null object pattern implementation. If the ScoredValue class receives a nil as the first parameter, it can just return “N/A” for us and we don’t have to deal with yet another design pattern and layer of abstraction in our system.

Given the relative simplicity of the genetics hash compared to the lipids class, why, then, am I using a class to define access to a value via a method, which is essentially just a key to get the value that I need? What benefit am I introducing to my system by modeling the access to my data in this way? I honestly don’t think I’m adding any value in this case, and as I’ve shown with my previous discussion of nil checks, I think I’m actually doing more harm than good.

What About Encapsulation Of Business Logic, or … ?

You might be tempted to run off and say that you don’t need custom classes, ever, in your ruby apps. Don’t. That’s just not true. There are times when a custom class or model is appropriate. You may have some business process that needs to be modeled and encapsulated correctly, etc. Hashes are not a panacea or silver bullet. They are, however, a great tool to have in your tool belt. I, for one, am beginning to re-evaluate what I now think is an excessive us of hand-rolled classes and ugly, noisy nil checks.