How we got rid of the database–part 5

Preface

In our company we were looking for a way to radically simplify the way we implement our enterprise software. We wanted to get rid of accidental complexity introduced by using complex and expensive middleware and server software like RDBMS.

In part 1, part 2 and part 3 of this series I introduced some of the core elements of our CQRS/ES architecture. In part 4 I discussed some of the questions that readers and coworkers have when confronted for the first time with the ideas of command-query-responsibility-segregation (CQRS) and event sourcing (ES).

Tying it together

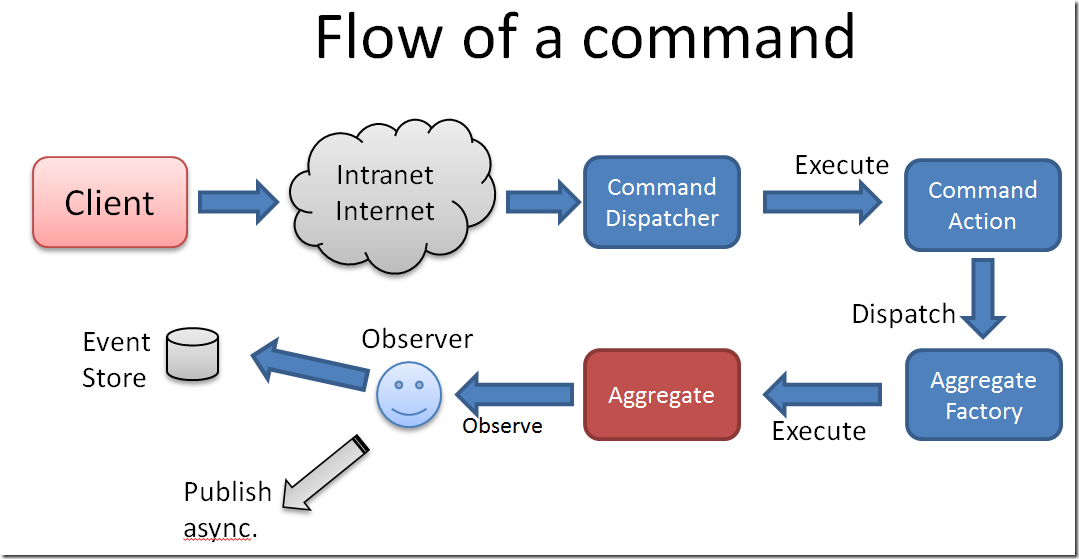

As promised in part 3 of this series I’ll try to bring everything together in this post. From part 1 (the magic triangle) we know that the client sends commands to the domain. Lets have a look at what happens here

The Silverlight client creates a command and sends it via a WCF service to the server. The WCF service on the service side forwards the command to a command dispatcher which in turn uses the IoC container to resolve the command handler that can handle this command. There can only be exactly one command handler per command registered in the IoC container. This is a direct consequence of the fact that a command always must have a single target. If no command handler is found, or more that one command handler for this particular command exists then this is a fatal error.

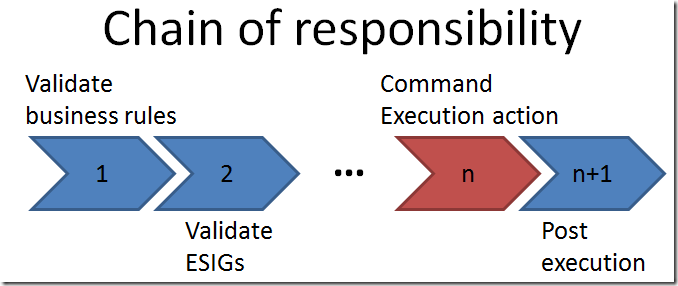

The command dispatcher then forwards the command to the command handler. In our system the command handler is implemented as a chain of responsibilities (also called a pipeline).

When the command enters the pipeline in the first step we test whether it would violate any business rule. If yes then the execution is aborted and the command result type is set to ValidationFailed and the violated business rules (text messages) are returned.

In a second step we test whether this particular command needs an electronic signature (ESIG) and if yes we verify that a valid ESIG is provided. Again, the command execution is aborted if the ESIG is missing or wrong and an error message is returned to the client.

There are more steps in our system which lay outside of the scope of this post.

Finally, if everything is fine so far the command arrives at step n, the command execution action. Here the command is executed. In our case the command is forwarded to the aggregate factory. The aggregate factory executes the following tasks

- analyze the incoming command and determine which aggregate instance the command targets.

- load all existing events for this particular aggregate instance from the event store.

- Create a new instance of the aggregate and re-hydrate the aggregate with the events loaded in the previous step

- forward the command to the aggregate instance</ul>

Contract

Before I can continue with code I have to introduce a couple of contracts (interfaces) that we use in our infrastructure to make the code as simple as possible.

First of all we recognize that every command or event that we deal with in our system is a message. Thus we introduce a message interface. Since the interface IMessage is already used by other code (e.g. messaging system) we use ICqrsMessage as the base interface.

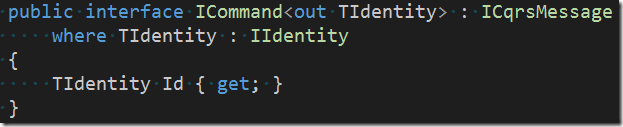

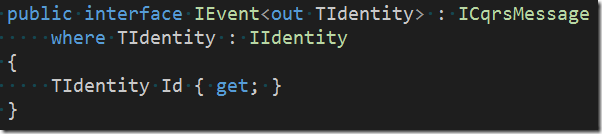

It is just an empty (marker) interface. But now we want to distinguish commands and events and we introduce the following two contracts

and

It is important to note that both interfaces are covariant (out) in the generic parameter TIdentity. This makes it possible to cast an ICommand

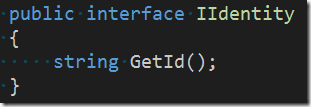

</font> to an ICommand </font> if Foo implements IIdentity. Finally we have the interface which all identities (IDs) used in our system implement

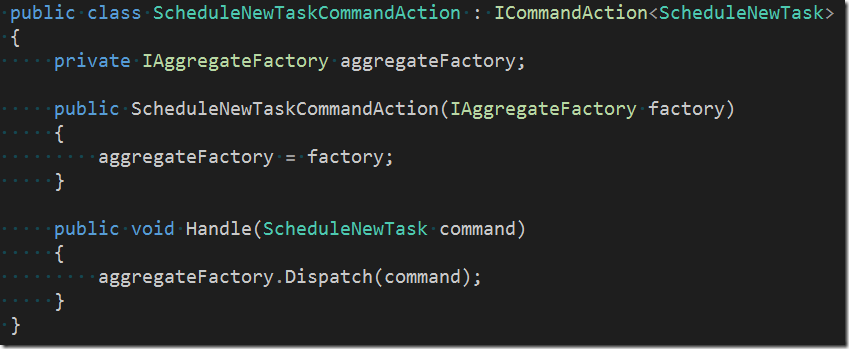

Having introduced these interfaces (or contracts) we can now continue to show the aggregate factory. The command execution action gets the aggregate factory injected

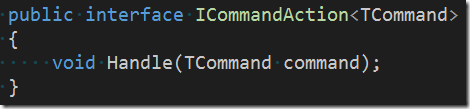

here the interface that each command action implements is simple and look like this

note that the Handle method is a void method. A command execution never returns data in CQRS.

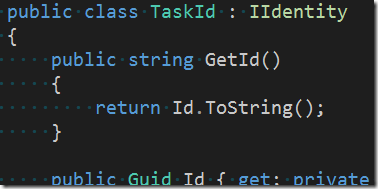

In order to make our code compile we need to adjust the definition of the ScheduleNewTask command and the TaskId identity that we introduced earlier. The TaskId is an identity and needs to implement the interface IIdentity

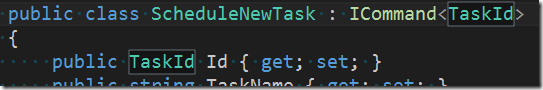

and the command needs to implement the command message interface

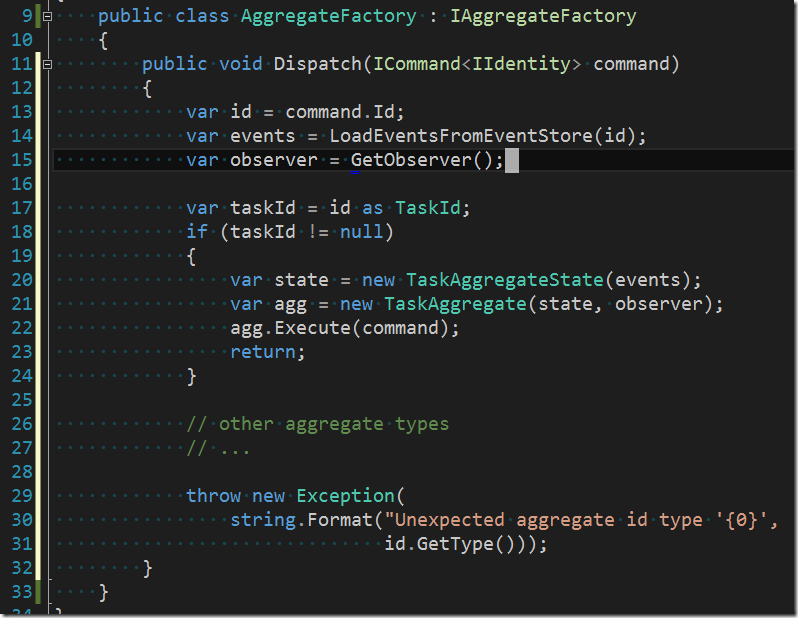

Now we should be able to compile and can continue with the implementation of the aggregate factory. We have this

On line 13 the ID of the aggregate that is target of the command is determined. Since we use typed IDs throughout the system the ID not only gives us the value but also it tells us which type of aggregate it targets (Task aggregate versus e.g. Animal aggregate).

On line 14 we load the events from the event store that have been previously stored for the aggregate with the given ID. This collection can be empty if the command is the first command in the life cycle of the aggregate.

On line 15 we get the observer that later on is injected into the aggregate. The observer is an infrastructure function that takes the event(s) that the aggregate triggers and handles them. Specifically the observer stores the event(s) in the event store and then publishes them asynchronously.

On line 17 we determine whether the target is a task or not. If yes, we create the state of the task from the events (line 20) and then we create the aggregate and inject the state and the observer to it (line 21). Finally we forward the command to the aggregate for execution (line 22) and return (line 23).

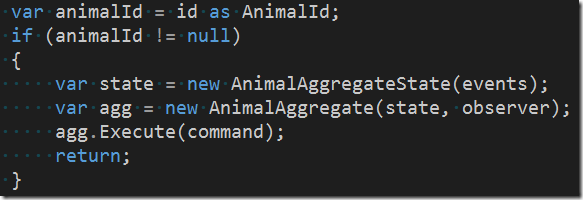

If we have other aggregate types in our system we repeat line 17 through 24 for each aggregate type, e.g.

For the moment I do not want to discuss the details of the two methods LoadEventsFromEventSource(…) and GetObserver(). I will explain the details of these in detail in a future post. Suffice to say that the observer has the following signature

It’s an action that has one input parameter, the event that it handles. We have learned above that each event is an IEvent

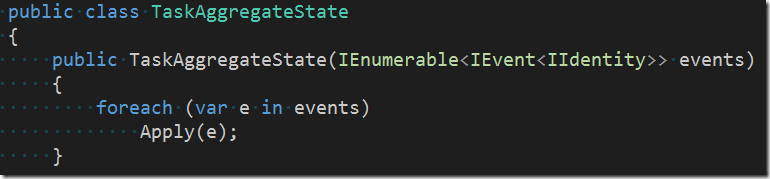

></font>. Let’s now revisit our Task aggregate and aggregate state that we introduced in an earlier post. Let’s start with the state.

the state has a constructor with one parameter, the collection of events injected by the aggregate factory. The state re-hydrates itself with these events (see the foreach loop).

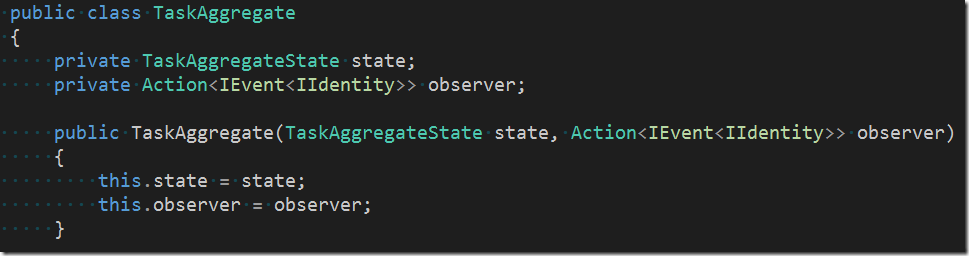

The aggregate on the other hand gets the state and the observer injected

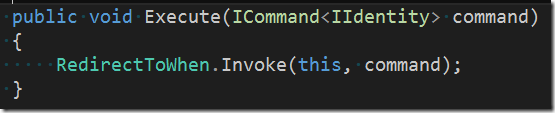

The aggregate also implements the Execute method which is called by the aggregate factory

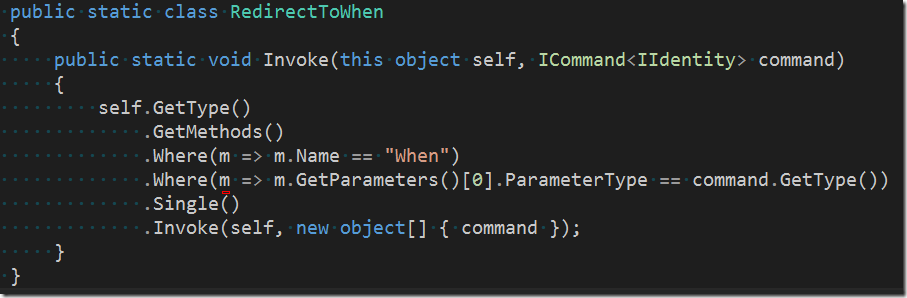

The RedirectToWhen is a static helper class with uses reflection to determine to which When method of the aggregate the command has to be forwarded. The code is very simple due to the fact that we use the convention to call all our methods on an aggregate that execute a command ‘When’ and that each of these methods has one single parameter, that is the command they handle.

Of course, in our production system the code looks slightly more complex since we cache the meta data to avoid repetitive use of (slow) reflection. But this series of posts it about the principles and not so much about technical details!

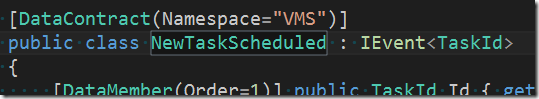

We do not have to forget to make our events implement to events contract, e.g.

That’s it, simple, isn’t it? Well you might disagree with me here… but the apparent complexity stems from the fact that the whole process had so many steps. Each step in isolation is really really simple, agreed? There is absolutely no “magic” or “rocket science” involved. We need no expensive tools of frameworks so far to achieve our goals. And that is one the essence of this series of posts: we can achieve our goals by using simple code and leaving alone expensive middleware or server software.

I have to admit, so far there is a pretty important piece missing in the puzzle. It is the queuing system that we use. But this will be the target of my next post.

Look back

Let me try to visualize once again how a command flows through the system

Code

You can find the sample code on GitHub.

Till next time!

- forward the command to the aggregate instance</ul>

- Create a new instance of the aggregate and re-hydrate the aggregate with the events loaded in the previous step

- load all existing events for this particular aggregate instance from the event store.