Three simple Mercurial rules

The following is highly opinionated, but it matches most closely to what typical Git workflows are. The nice thing about Hg is that its tools can hide the complexity of working with distributed version control systems (DVCS). That’s also a drawback, because if you don’t know what’s actually going on behind the scenes with your commits, you can get into some rather strange situations and complicated commit graphs:

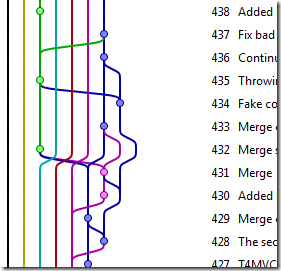

This is actually a relatively sane portion of the MVCContrib project. Now, dealing with public repositories with forks is a little bit different than internal team repositories, but the rules are quite similar. Here’s a picture from a team-based project, working on one line of development:

Uh…what? There’s only supposed to be one “line” of development, one truth of the current version, but can anyone look at this picture and have any idea what’s going on? I sure can’t.

But we can avoid spiderweb commit graphs and have a sane understanding of the progression of our software, with a three easy rules:

- Separate parallel areas of work with separate named branches

- Rebase local commits on the same named branch for incoming changes, merge between named branches. A named branch should never merge with itself.

- Push and pull only one branch, not the entire repository

So how does this translate into our daily workflow?

The daily workflow

When we’re first starting our work, we have to decide if this is a separate area of work we’re working on, or is this part of an existing line of work. If it’s existing, we can work off of that branch. If it’s new, we’ll start a new branch. Our workflow then is:

- hg branch MyNewFeature

- work work work

- hg commit -Am “Committing whatever”

- work work work

- hg commit -Am “More work”

At this point, we want to push our work up to the remote server. But we only ever want to push our current work, not everything we’ve ever done. I really never push my entire repository, but my current line of work. The reasoning is that pushing the entire repository assumes I’m integrating multiple lines of work. But I only want to integrate my current line of work, and I only want to work in one line at a time.

If this is the first time I’ve pushed this branch:

- hg push -b . –new-branch

If I’ve already pushed this branch:

- hg push -b .

The “-b .” command means just push the current branch, and not anything else. That’s #3 in our rules.

But what about integrating upstream changes?

- hg pull -b . –rebase

I pull in ONLY the current branch I’m working on, rebasing my changes on top of incoming commits. This ensures a single, linear commit history for every named branch. A named branch never merges with itself, with is the source of most of the confusion and problems with DVCS I see these days. People need to correct some change in the history, and can’t figure out what has happened because of the crazy commit history. I don’t care what other people are working on, I’m only concerning myself with integrating the work that I’m doing.

What happens when we want to merge our line of work into a different line (such as a trunk/master/default branch)?

- hg merge trunk

- hg commit -Am “Merging trunk” –close-branch

- hg push -b .

- hg checkout trunk

- hg merge MyNewFeature

- hg commit -Am “Merging MyNewFeature”

- hg push -b .

What’s the end result of this picture? A commit history that logically separates lines of work into single, linear commit histories. Named branches separate logical areas of focus. The begin and end of logical areas of work are clearly defined in our commit history.

The nice thing about this workflow is that it doesn’t assume any sort of branching strategy – if you have branches per story/developer/release or whatever. It just defines a manner of working effectively in a single branch, and rules for integrating changes between branches.