Saga implementation patterns – variations

In the previous couple of posts, I looked at the two main patterns I run into when looking at sagas:

- Command-oriented (request/response) in the Controller pattern

- Event-oriented (pub/sub) in the Observer pattern

Of course, these aren’t the only ways our saga could behave. We could have any combination of these.

Publish-Gather

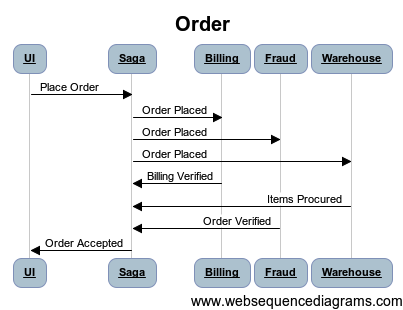

Looking back on our McDonald’s example, we could improve our situation a little bit. We could have a situation where we want a command to start a saga, then have the saga itself publish a message. It would then wait for events to come back (ignoring order):

The advantage here is that we only have one entry point to our saga. We don’t have to worry about our saga potentially getting started by any number of messages that were pushed out.

When you place an order at McDonald’s, it’s almost always the cashier that places the tray on the table. When stations are finished with fries, sandwiches etc., they don’t really come to the counter and make a decision “do I need a new tray?”. The tray is already there, so our saga has already started.

There’s also nothing stopping our downstream processes from spawning off additional sagas – but that’s hidden from our originator.

Reporter

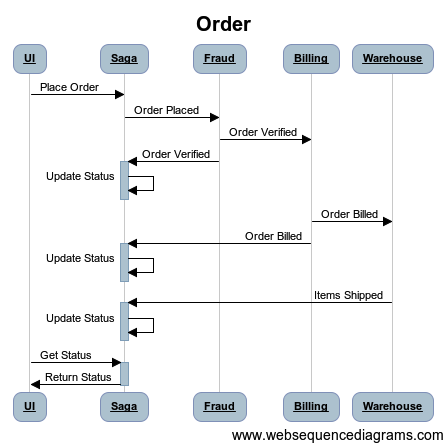

Another role our saga can play is one that doesn’t make decisions, but instead merely reports status:

This is a situation where a saga might never actually complete, and goes on forever. Its role is to communicate status of a longer-running process in the back-end, not for coordination purposes, but for reporting purposes.

The reason we might want a saga for this case is we still don’t know what order we’ve received messages from downstream systems we don’t own. As we learn about downstream events, we can evaluate them based on our knowledge of the overall business process. An order can’t go backwards from “shipped” to “verified”, so receiving these out of order doesn’t change the fact that the order shipped! Note: this doesn’t necessarily imply the status is in the saga entity itself. It still could be separate.

Keeping it as a saga lets us handle messages in any order and keep some centralized logic around interpreting these messages.

Sagas/process managers are pretty flexible in how we compose the pieces together. I often get questions around “why can’t I design a saga like a workflow?” And the answer is that sagas are meant to handle cases where I don’t have a directed workflow, where I live in a world where messages can arrive out of order.

It’s a much easier world to scale – but we need to accept the complexity it brings on the other end.

There is another clear downside here – we have shared state amongst multiple messages and handlers, which can potentially lead to scaling problems. Next time, we’ll look at scaling sagas.