How We Do Things – Evolving our Specification Practice

This content comes solely from my experience, study, and a lot of trial and error (mostly error). I make no claims stating that which works for me will work for you. As with all things, your mileage may vary, and you will need to apply all knowledge through the filter of your context in order to strain out the good parts for you. Also, feel free to call BS on anything I say. I write this as much for me to learn as for you.

This is part 6 of the How We Do Things series.

This post was co-written on Google Wave with my colleague Cat Schwamm, who keeps me sane every day.

In this part we will explore how specification practice has evolved in our team, from a very waterfallish BDUF approach to what currently is a very lean approach to specification. In the next part of the series we will talk stories and mockups and other tools we employ to make the magic happen.

Where we came from

We began our large LIS project in late 2004, starting with about 6 full months of writing specifications and designing the database. We created reams of documentation for each application complete with use cases that we knew we wouldn’t even implement until after the first version was released (sidebar: some of those still haven’t been done). We defined more than 100 tables of heavily normalized database schema. Before one line of code was written, we had spent six months of project budget.

As development continued on the project we found ourselves diverging from the specifications that had been created. The documents became little more than a roadmap, with the bold headers on functional groups and the basic usage stories becoming the guidelines that we followed. Much of the detailed specification and database schema went out the window as the system took shape and people began to see and give feedback on what was being produced. Too much specification gave us a false sense of “doing it right” and led us down many wrong paths. Balancingrework with completing planned features became a costly chore.

By the time the project was complete, it was clear that much of that up-front work had been wasted time and money. Had we top-lined the major milestones of such a large project, detailed a small set of functionality, and started developing iteratively, the system would have taken form much sooner, allowing for a tighter feedback loop and much less overall waste.

How we do it now – Overview

Lessons learned, we set about improving how we do specification. I already talked a little about this in the posts on planning, so please review those if you haven’t seen them yet. [part 1] [part 2]

When planning a new project of any size, we take an iterative approach. We start at a very high level, and strive to understand the goals of the project. What need does it serve? Who will be using it? Are we competing with something else for market share? Is there a strategic timeline? What’s the corporate vision here? What are the bullet points? We will fill in details later. We only want broad targets to guide us further.

When we get closer to development, we start to identify smaller chunks of functionality within each of those broad areas. This is still pretty high level, but done by business analysts and management on the IT team. We start to identify MMFs (minimal marketable features) and group them up in order of importance to help determine next steps.

MMFs in hand, we take the first one and start defining it further. This is where the information from the planning post comes in. We start to write stories (Cat has a great post detailing how to build effective stories). The other information gathered to this point sits dormant, with as little specification work done as possible, until such time as we are getting closer to working on it.

Over time, and only as needed, we put more and more specification on the system, and this is done in parallel with development. In fact, often the most specific information can only surface during development of those features, as they take shape, and as we understand how users will react. Specification should be every bit as iterative as coding.

Reduced to its essence, we JIT specification at many levels to allow maximum flexibility to change direction with minimal wasted work.

Gemba is an essential part of specification

It’s often the case that a team relies on “domain experts” to provide them with the specifications they need to build software. This is the BDUF way – gather in committee and have the all-knowing user tell you what to build. Fail.

Cat sez:

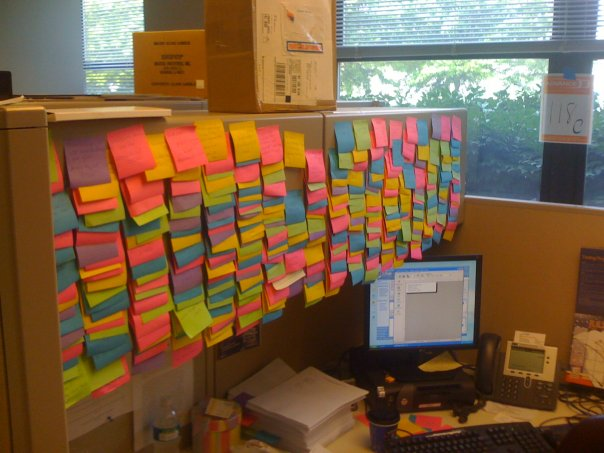

The dev team works out of the corporate office in Florida, while the actual laboratory is located in upstate New York. As a result, it is often an exercise of the imagination to figure out the best way to create things for them. Before I visited the lab, I relied on information from others, emails back and forth to the lab crews working all weird hours of the night, and my knowledge of the applications currently in existence. I really only ever got half the picture, and it was difficult to ensure that the things I was specifying would fit into the lab users workflow well without actually knowing what was going on up there. When I visited the lab my whole world was changed. Actually seeing how users interacted with the software and seeing ways they would work around what we didn’t have (open Excel or Word documents on their desktop, a wall covered in post-it notes). Just from walking around talking to people for 2 days, I probably got 50 requests. And they never would have asked for them; they would have just kept suffering. Being there showed me everything about how they worked and a million ways I could improve their lives. The experience was invaluable to both me and them, and each subsequent trip has just improved my knowledge of the way we work and the way they interact with our software.

There is no substitute for a certain amount of domain expertise being resident in the team room. Your domain experts are experts only in their domain. They may know the workings of a histology laboratory inside and out, but if you ask them to design a system to support that lab, they’ll come back with something that looks an awful lot like excel and post-it notes.

Yes…this is a workaround someone had for something our system didn’t do. It’s been fixed 😉

Lean has a concept of the gemba attitude and genchi genbutsu, essentially, being in the place where the action happens. Developers and business analysts have to work with the domain experts, in the place where the work happens, and observe the true workflows in place before hoping to design a system to support them. You cannot get this information from sit down meetings and emails with domain experts. You must go and see for yourself, or you will miss things.

In the next post we will talk specifically about the tools and techniques we use to specify work, and how we combine them to form complete pictures of a system (spoiler alert: it ain’t just stories).</div>

Technorati Tags:

how we do it, improvement, lean, management, quality, software, team, planning