Dependency Injection Is NOT The Same As The Dependency Inversion Principle

A long time ago, when I first started blogging with LosTechies, I wrote up a few posts on Dependency Inversion and Dependency Injection, and how I finally started to understand what Dependency Injection was all about. At the time, I thought DI was DI was DI – whether you called it “injection” or “inversion”.

Injection != Inversion

A year or so after those two blog posts, I wrote an article on the SOLID software development principles for Code Magazine. In the process of writing that article, I had my then coworker, Derek Greer, review what I was writing. This turned out to be the single best thing I had ever done for my understanding of SOLID, because Derek was kind enough (and willing to put up with my stubbornness) to show me how my understanding of Dependency Inversion was wrong. He took the time to walk me through the original Uncle Bob articles, explain where I was mixing up Dependency Injection with Inversion, and set me straight on the subject. The result was a great article that is still fairly popular – and I owe a big thanks for Derek for his help in correcting my understanding.

Fast forward to today, though, and I continue to see other people making the same mistake – even in ruby. So, In an effort to help others understand what Dependency Inversion is and is not, I’m re-posting the DIP section of my article here. I realize that some of the content won’t make sense without the context of the rest of the article. However, the general principle should be evident, and you can click through any of the links to the article to read it in it’s entirety.

(Legalese: The following content originally appeared in the January/Feb 2010 issue of CODE Magazine, and is reproduced here with permission)

The Dependency Inversion Principle

The Dependency Inversion Principle has two parts:

- High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions.

- Abstractions should not depend upon details. Details should depend upon abstractions.

Think back to the last time you wanted to turn on a lamp to help light an area of a room. Did you have to cut a hole in the wall, dig around for electrical wires, strip them bare, and solder the lamp directly into the wiring of the house? Of course not (at least, I hope not!) The electrical outlet provides a standard interface for such an occasion. No one, in most of the industrialized world, would expect to solder a lamp directly into the electrical wiring of the building. Additionally, no one expects to only be able to plug in a lamp, to an outlet. We expect to plug in lamps, computers, televisions, vacuums and other devices. The standard, 120 volt, 60 hertz power outlet has become a ubiquitous part of society in the United States.

The same principle also applies in software development. Rather than working with a set of classes that are hard wired (tightly coupled) to each other, you want to work with a standard interface. Furthermore, you want to ensure that you can replace the implementation without violating the expectations of that interface, according to LSP. So, if you’re working with an interface and you want to be able to replace it, then you need to ensure that you are only working with the interface and never with a concrete implementation. That is, the code that relies on the interface should only ever know about the interface. It should not know about any of the specific classes that implement the interface.

Policy, Detail, and Abstraction Ownership

Another way to think about DIP is to say that policy (high level) should not depend on detail (implementation), but detail should depend on policy. The higher-level policy should define an abstraction that it will call out to, where some detail implementation executes the requested action. This perspective can help to illustrate why this is the dependency inversion principle and not just a dependency abstraction principle.

As an example of why detail depending on policy is an inversion of the dependency, look at the code you wrote into the FormatReaderService. The format reader service is the policy. It defines what the IFileFormatReader interface should do-the expected behavior of those methods. This allows you to be concerned with the policy itself, by defining how the format reader service works without regard for the implementation detail of the individual format readers. The format readers, then, are dependent on the abstraction provided by the reader service. Both the service and individual format readers, in the end, are dependent on the abstraction of the format reader interface.

Correcting Coupling by Inverting Dependencies

You know that it’s not reasonable for a class to have zero dependencies-to have zero coupling. You would not have a usable set of classes if you had zero coupling. However, you also know that you want to reduce direct coupling whenever possible. You want to decouple your system so that you can change individual pieces without having to change anything more than the individual piece. The Dependency Inversion Principle is the key to this goal. By depending only on an abstraction such as an interface or base class, you can correct the coupling of the various parts of the system. This allows you to re-compose the system with different implementations.

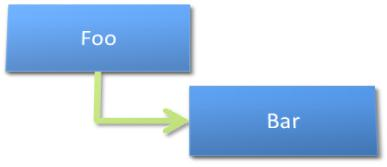

Consider a set of classes that need to be instantiated into the correct hierarchy so that you can get the functionality needed. It’s easy to have the highest level class-the one that you want to call-instantiate the class at the next level down, and have that class instantiate its next level down, and so-on. Figure 14 represents a standard object graph where the higher-level object-the policy-is dependent on and coupled directly to the lower-level object-the detail.

Figure 14: Policy coupled to detail.

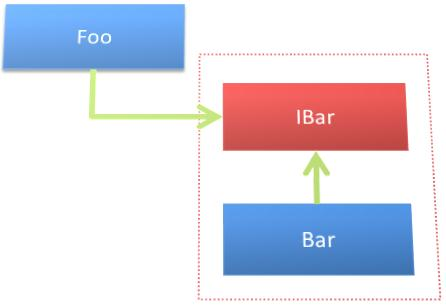

This creates the necessary hierarchy but couples the classes together, directly. You would not be able to use Foo without bringing Bar along with it. If you want to decouple these classes, you can easily introduce an interface for Foo to depend on and Bar to implement. Figure 15 illustrates a simple IBar interface that you can create from the public API of the Bar class.

Figure 15: Decoupling with abstraction.

In this scenario, you can decouple the implementation of Bar from the use of it in Foo by introducing the interface. However, you’ve only decoupled the implementation by separating the interface from it. You haven’t inverted the dependency structure yet and you haven’t corrected all of the coupling problems in this setup.

What happens when you want to change Bar in this scenario? Depending on the change you want to make, you could have a rippling effect that causes you to change the IBar interface. Foo depends on the IBar interface, so you must change the implementation of Foo as well. You may have decoupled the implementation of Bar, but you have left Foo dependent on changes to Bar. That is, the Policy is still dependent on the Detail.

If you want to invert the dependency structure and have the Detail become dependent on the Policy, then you must first change your perspective. The developer working with this system must understand that you should not merely abstract the implementation away from the interface. Yes, this separation is necessary, but it is not sufficient. You must understand who owns the abstraction-the Policy, or the Detail.

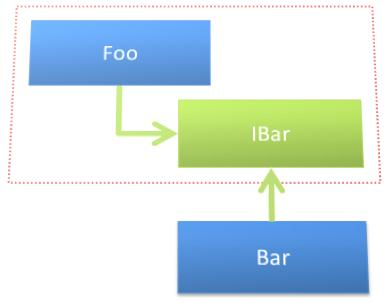

The Dependency Inversion Principle says that Detail should be dependent on Policy. This means that you should have the Policy define and own the abstraction that the detail implements. In the Foo->IBar->Bar scenario, you need to treat IBar as part of Foo and not just a wrapper around Bar. Nothing may have changed structurally, but the perspective of ownership has shifted, as illustrated by Figure 16.

Figure 16: Policy owns the abstraction. Detail depends on policy.

If Foo owns the IBar abstraction, you can place these two constructs in a package that is independent of Bar. You can put them into their own namespace, their own assembly, etc. This can greatly increase the illustration of what class or module is dependent on the other. If you see that AssemblyA contains Foo and IBar, and AssemblyB provides the implementation of IBar, it is easier to see that the detail of Bar is dependent on the policy defined by Foo.

When you have the dependency structure inverted correctly, the ripple effect of changing the policy and/or detail is now correct as well. When you change the implementation of Bar, you are no longer seeing an upward ripple of changes. This is due to Bar being required to conform to the abstraction provided by Foo-the detail is no longer dictating changes to the policy. Then, when you change the needs of Foo, causing a change in the IBar interface, you now have changes that ripple down the structure. Bar-the detail-will be forced to change based on the policy changing.

Decoupling and Inverting the Email Sending System Dependencies

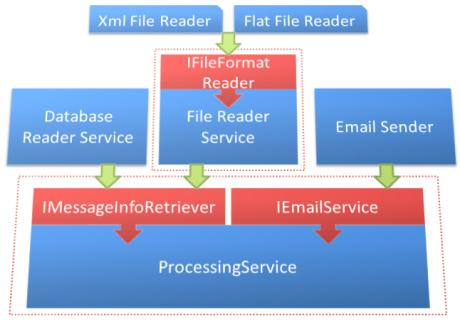

Looking through your codebase you see that the IFileFormatReader is already an instance of Dependency Inversion. The FormatReaderService class owns the definition of the format reader interface. If the needs of the format reader service changes, you will likely see ripples of change down into the individual format readers. However, if an individual file format reader changes, you will not likely see changes ripple up into the format reader service. This makes you wonder where else you can invert the system’s dependencies.

The first thing you want to do is decouple the logic of getting the log message, and sending it as an email, from the form. You don’t mind the references to the two reader services and the email sender, but having the explicit knowledge of what to call when is a little questionable in your mind. You recognize that the process is actually duplicated in the form: once for sending from a file, and once for sending from a database. And then you remember all the other departments that are using this as well, and start to wonder just how much duplication of the process really exists. Additionally, some of your friends have been talking about “unit testing” recently. They say that you should ensure the real process logic that you are testing is encapsulated into objects that don’t have references to external systems.

With all of this in mind, you decide to create an object called ProcessingService. After a few minutes of moving code around to try and consolidate the process, you realize that you don’t want the processing service to be coupled directly to the database reader or file reader services. With an additional moment of thinking, you recognize a pattern between the two: the “GetMessageBody” method. Using this method as the basis, you create a new interfaced called IMessageInfoRetriever and have both the database reader and file reader services implement that.

This interface allows you to provide any implementation you need to the processing service. You then set your eyes on the email service, which is currently directly coupled to the processing service. A simple IEmailService interface solves that, though. Figure 17 shows the resulting structure.

Figure 17: Inverting the dependencies of the processing service and file reader service.

Passing the message info retriever and email service interfaces into the processing service ensures that you have an instance of whatever class implements those interfaces, without having to know about the specific instance types.