Saga implementation patterns – Controller

In the previous post on saga implementation patterns, we looked at the Observer pattern. In that pattern, the saga was a passive participant in the business transaction, similar to how many fast food restaurants fulfill orders. But not all food establishments fulfill their orders in this way, and find more efficient means of doing so.

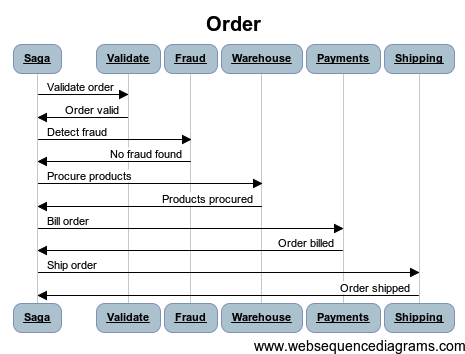

Instead of merely observing events from other entities, we can have our saga perform an active role in the process. The saga controls the flow directly, issuing commands to specific workers, waiting for replies, and moves on to the next step. It works well for processes that need to happen in a certain order:

Our saga has a specific order, and many times, steps later in the saga need information from previous steps. In order to enforce an order, we need to take control of the process. We can’t ship before we bill, and we can’t bill before we procure, etc.

Unlike the Observer saga, the Controller saga directs the workflow by issuing commands and using replies to determine the next step. If a step fails or comes back with some error condition, we can determine an alternate flow. We can take compensating actions or direct the saga into another queue for manual intervention.

The key here is that our Controller saga directs with commands, and our Observer gathers events. Like our Observer saga, we can look again to the food industry to see an everyday example of a Controller saga in action.

Fast food messaging – Which Wich

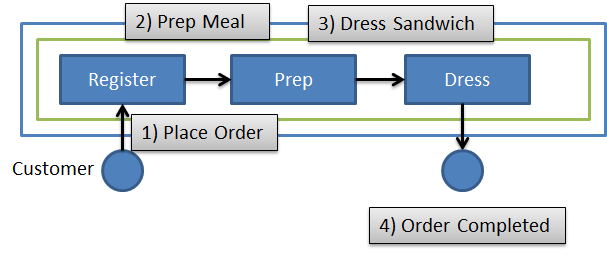

While our McDonald’s example featured many steps that could execute in parallel, with no real interaction or dependencies, our local sandwich shop of Which Wich is completely the opposite. In this shop, the entire process is a single pipeline:

Our customer begins the process by placing an order. At Which Wich, this is done in a rather ingenious manner. The customer picks a paper bag labeled with a main ingredient. On the bag are lists of toppings alongside little bubbles. The customer uses markers to color in the bubbles indicating what toppings they want on their sandwich. Finally, the customer puts their name on the bag so that when their order is completed, the person delivering the sandwich knows whom to deliver to.

Along the entire length of the store is a steel wire, where your bag is clipped to. The cashier slings your bag to the next station, where the next step processes that order, in the order the bags were received.

It’s still not *quite* a central controller in our example – we don’t have that one person whose job it is to coordinate the entire pipeline. Instead, it’s built in to our queues. If we wanted a real world example of a controller in a restaurant, we’d need to venture out of fast food into one where an executive chef managed a high-end restaurant. But I’ve never been one to let the truth get in the way of a good story.

There are quite a few benefits to this approach:

- Steps can be explicitly ordered and correlated

- No contention of resources, since no two steps for a single saga are executing at the same time

It’s not without its drawbacks:

- Overall processing time can increase, since we’re forcing a serial processing of steps

- Scaling can again be difficult because of the shared state and shared queues of many implementations

It turns out that our above example is better suited to another messaging pattern. But to get there, we’ll look at scaling sagas first, what problems we run in to and potential solutions.